Chapter 21

Maintaining Daily Operations

Part 1: Office Operations

Efficiency is doing things right; effectiveness is doing the right things.

Peter Drucker

capacity utilized

effectiveness

efficiency

Efficiency and Effectiveness

In operating a productive practice, dentists need to be both efficient and effective.

Efficiency

Efficiency looks at how cheaply something is done. The focus is costs. The intention is to save money, time, or effort regardless quality. To become more efficient, people simply must lower costs. Efficiency measures productivity at the individual process level, regardless the collateral effects of the decision (Table 21.1). It often requires conforming to norms. In this way, the process is no worse than others in the industry. It examines internal, technical issues. The result is to improve profitability by working harder and quicker.

In dentistry, efficiency comes from doing procedures correctly the first time, without remakes. Not only does the dentist have the cost of additional materials, staff, and lab charges, but he or she has also lost the additional production he or she could have during the time spent with the remake. Clinical decision making is the prime factor that increases clinical speed.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness looks at how well something is done. Here, the focus is the benefit or outcome of the process. The intention is to improve quality at a higher level than the individual process, thereby raising performance levels. It measures how well the job gets done, or the correctness of a product or service. Effectiveness then is a quality measure, not a cost measure. It examines external, strategic results. The outcome of effectiveness is improving profitability by working smarter.

As an example of the difference in a dental practice, dentists can be more efficient (lowering costs) if they use a foreign lab. However, dentists may be less effective in crown and bridge work because of more remakes and lower patient satisfaction that result. So here, effectiveness trumps efficiency. Using the foreign lab costs less, but dentists are not doing their job as well. So simply doing something less expensively does not necessarily lead to more profit. In all of office decisions, dentists must be sure that they are both efficient and effective.

Table 21.1 Efficiency versus Effectiveness

| Efficiency | Effectiveness |

| How cheaply you do something | How well you do something |

| Costs | Quality |

| Process | Outcomes |

| Working harder, quicker | Working smarter |

Capacity

Capacity is the ability of the office to see patients. It is the maximum number of patient visits (or appointments) that the office has available for a given period. The way dentists plan and organize the office ultimately decides the ability to see patients. This configuration can (and should) change over time. As the practice matures, the number and type of patient visits change. Although capacity defines a dentist’s ability to see patients, marketing brings those patients in and fill available chair time. Both sides (driving demand and then seeing those patients generated) need to be satisfied for success. The dentist’s practice philosophy guides the changes made in the operational and marketing systems to achieve goals.

What Determines Capacity

Capacity is affected by all of the management decisions dentists make in the office.

Number of Operatories

The number of operatories has an obvious and important effect on the dentist’s ability to see patients. However, the dentist must be sure that proper staffing levels support the operatories. Seven operatories will not let a dentist see more patients than one operatory, without staff support. The additional six operatories become nothing but expensive waiting rooms. Generally, dentists assign one chairside assistant to one operatory. The assistants are responsible for chairside assisting during patient procedures, set up, break down, and disinfection of the operatory between patients.

Operator Speed

The dentist’s speed when doing patient procedures determines the length of appointments and therefore the number of available appointment slots. Operator speed is not really dependent on “hand skills” and physical speed. Speed in completing patient procedures depends on the dentist doing the procedure correctly without remakes. This means that the dentist and staff are knowledgeable about each step of every procedure and that they take their time to do procedures correctly, as opposed to just doing them quickly. Operator speed then increases automatically with experience. As staff members become more accustomed to the dentist and better trained in specific procedures, the dentist can move more quickly through procedures without internal “wait time” for mixing materials, repositioning patients, or other small inefficiencies. That training does not just “happen.” It is the dentist’s responsibility to ensure that staff training is an ongoing office function.

Office Hours

The more hours that a dentist is open, the more appointments are available. There are some limitations. Most people want time away from the office for personal and family enjoyment. So although working 80 hours a week opens many appointment slots, most dentists are not willing to make the sacrifices involved in the trade off. (The typical practicing dentist works 35 hours per week, according to the American Dental Association [ADA].)

Many patients want to come to the dentist during nontraditional hours (evenings and weekends). If a dentist keeps “bankers’ hours” (9 to 5 Monday through Friday) then he or she may lose some patients to other dentists who are open during those “off” hours. Although the marketing and operational considerations encourage use of off hours, staff considerations do not. If staff works more than 40 hours per week (in most states), then they must receive overtime pay. Staff members generally do not want to work evenings or Saturdays for the same reasons dentists do not. (They would rather spend time in personal or family pursuits. They may have children in day care or after-school programs.) So although there are reasons to work extended hours, the dentist must consider trade-offs.

Early in a dentist’s practice life cycle, he or she needs to generate patients for the practice. To do this, the dentist may keep more off-peak hours (evenings and weekends). If the available appointments cannot be filled, he or she may close the office for some traditional business hours to decrease costs. As the practice becomes more mature, the number of patients waiting for treatment increases. The dentist can then cut back on off-peak hours, forcing patients into the more traditional appointment slots. If the patients cannot make these appointments, they may go elsewhere for treatment, but the dentist will generally have other patients waiting to fill the appointment slot.

Number and Types of Staff Members

Operational decisions do not affect facility costs greatly, unless the dentist decides to expand the office to increase capacity. The dentist pays rent regardless the number of hours worked. Utility costs may be higher with additional or evening hours, but the lights are on for all working hours regardless. The biggest cost item is staff cost. If a dentist has existing staff members work additional hours, he or she may have overtime costs. The dentist may have to offer differential pay to induce someone to work nontraditional hours. He or she may also have extra costs as the result of hiring additional part-time staff members.

Many dentists hire part-time staff. They may hire them to work during a busy time of the day (e.g., evenings) or to do a particular function in the office (e.g., collecting accounts). With either type, dentists only hire people for the times that they are needed most, improving office efficiency.

Chairside Assistants

As a rule, a dentist needs one chairside assistant for each operatory. (If a dentist has seven operatories and one assistant, he or she cannot see many more patients than with one operatory and one assistant.) Fewer assistants lead to the extra chair being unused, more and the additional staff are not as needed.

Expanded Functions

If the practice state allows expanded functions by trained (or certified) dental assistants, then additional operatories can significantly increase capacity. These staff members can be completing intraoral procedures while the dentist sees additional patients.

Receptionists

Receptionists are necessary for smooth and efficient operation. A lack of receptionists will decrease recall patient visits (because the receptionist is too harried to manage the recall system effectively). This also leads to a decrease in overall patient visits (as a result of inadequate scheduling procedures.) As a rule, one receptionist can handle up to 1,000 patients per quarter (18 to 20 per day) with no decrease in effectiveness. As the number of patients increases above this number, office capacity decreases unless additional receptionist help is hired.

Hygienists

Hygienists increase capacity by freeing the dentist to see other patients (if there are adequate chairs available). If the office does not have enough operatories available, then the hygienist merely trades chair time with the dentist. The total capacity remains the same. They contribute to increased production and profit in the office. Hygienists also generate demand for the practice by seeing additional diagnostic (recall) patients that have other work to be done.

Owner Wants, Needs, and Desires

The owners’ wants, needs, and desires heavily influence office capacity. Some dentists do not want a large, “run and gun” practice. They prefer a more intimate, personal style of practice. Neither extreme is right nor wrong, merely personal preference. Regardless of the practitioner’s desires, an efficiently run practice that fully uses available capacity will be more profitably than a less efficiently run one.

Office Systems

The way that office systems are structured also affects capacity. If a dentist organizes patient scheduling around 10-minute blocks, then he or she can see more patients than if 15-minute blocks are used (assuming adequate patient demand and operator ability). If the instrument management system is not able to provide enough sterile instruments sets, there will be a capacity limitation.

Capacity Utilization

Capacity utilization measures the actual use of potential appointment time. It is calculated by dividing capacity (potential patient visits) by the number of actual patient visits for a period. The result is the percentage of available appointments (chair time) that were actually filled. Ninety percent use and above is very good; 80 to 90 percent is OK; and below 80 percent shows that the office resources are not well used. Early in the practice cycle, capacity utilization may be lower as available appointment time goes unused. As capacity utilized increases above 90 percent, it signals the need to expand capacity or to become more efficient to increase profit.

Capacity utilization is the primary measure of office efficiency. It does not depend on the number of operatories (chairs) or staff. (Both an eight-operatory office and a one-operatory office should have their capacity well used.) Because a significant part of dental office costs are fixed, it becomes important to use those fixed costs efficiently. Both large or small offices can be efficiently operated. This measure suggests if this is happening.

Increasing Patient Visits

Patient visits then are the driving force of a profitable dental practice. The key to maintaining efficiency (high capacity utilized) is to increase capacity as dictated by patient load. There is a need to anticipate growth in patient visits. (Dentists do not want to turn people away because they do not have the capacity to see the patients, especially early in the practice life when they are trying to build patient pool.) So the dentist increases capacity in anticipation of additional patient visits.

A practice’s service mix describes the types of dental procedures that the office does. Patient visits are divided into three types: diagnostic, basic services, and complex (major) services. Diagnostic visits involve new patients and routine recare (recall) procedures. They are where the dentist identifies additional work that a patient needs. Basic care includes restorations, endodontics, and surgical procedures. These visits prepare the way for the complex visits, which generally involve laboratory work and multiple-visit procedures. Each type of visit is necessary for a profitable practice. Expanding the service mix (by taking continuing education to increase or improve the types of procedures done) increases the number of patient visits within the office.

Marketing efforts, both internal and external, are a common way to generate additional patients. These include making more nontraditional hours available, changing credit and collection policies, and increasing insurance plan participation. Aggressive dentists may buy another practice or merge practices to increase patient pool.

Daily Scheduling

Hours

Dentists typically work about 40 hours a week, 32 of them in direct patient contact. Most offices do not work more than a 9-hour day; they find longer days too exhausting, although a few offices work fewer, longer days. For example, some work three 12-hour days. Most state employment laws require that a lunch break (unpaid) is provided after 4 hours of work. This varies from 30 minutes to an hour.

Many offices schedule early or late hours to accommodate patients. If a dentist does this, he or she should be sure not to work late one day and open early the next. This simply does not give people enough time from work. Evening hours are lucrative. Many patients who work (and have dental benefits) enjoy the evening-hour appointments. Saturday hours can be lucrative. Often, patients schedule these visits with good intentions, but when the time comes, they find that they would rather have the time off. They then cancel or do not show for a visit, leaving the dentist and the staff in the office on a beautiful Saturday.

Daily Huddle

The daily huddle is a short meeting at the beginning of each day. During the meeting, the staff discusses the schedule for the day, looking for potential conflicts or problems. For example, if the office has one nitrous oxide oxygen analgesia unit and two patients require the service, then one of them needs to be rescheduled. This is also the time to discuss if periodic maintenance patients require radiographs, to ensure that all patients have been contacted for appointment reminder, and checking to be sure that the laboratory has returned cases for scheduled patients. Each of these checks avoids a scheduling problem and improves patient flow and treatment.

Ways To Become More Efficient

Dentist can become more efficient without changing the capacity of the office. A dentist can streamline processes, using new or improved procedures to replace old ones. New materials may set more quickly or allow fewer steps in a process, decreasing time required for placement. Using a new technology (such as digital radiography) allows for less time in treatment. Over the long haul, dentists can save more in time (and additional procedures) than the technology costs to install. Adding a staff member is a large investment, but if he or she increases office collections more than he or she costs, the addition is a good investment.

If the capacity of the office is not fully used, then the primary focus should be on increasing the percent of capacity that is used. A dentist can do this either by increasing patient visits or decreasing capacity (and the associated costs). Increasing visits involves all of the internal and external marketing efforts that are described elsewhere in this book. Dentists should also check scheduling to be certain that they are using the time available best to advantage. Dentists can decrease capacity by decreasing hours, making the time that they and the staff are in the office more productive. (Dentists do not want to decrease hours to the point that it becomes difficult for patients to schedule appointments.) Dentists can also decrease capacity by decreasing the number of staff members or the hours that they work.

If the office capacity is fully used, then there are different solutions to the efficiency question. If there are adequate patients and a dentist has not reached maximum capacity, then he or she can increase capacity through moving to a new office space, adding operatories, adding staff to maximize the use of the space, or increasing hours that patients are seen. If, on the other hand, a dentist’s capacity is as large as he or she wants it to be, then he or she should increase efficiency and profitability. A dentist can do this by some combination of an increase in fees, a stricter credit and collection policy, and changing insurance plan participation (eliminating lower-paying plans).

Part 2: Office Accounting Systems

Don’t go around saying the world owes you a living; the world owes you nothing; it was here first.

Mark Twain

Charge and payment

Patient payment

Insurance payment

Medicaid payment and adjustment

Professional discount

Returned check

account ledger

account payable

account receivable

annual report

assignment of benefits

audit trail

back-ordered supplies

bank deposit

bank deposit verification

bookkeeping

bulk payment

business analysis summary

cash control

cash flow

cash transactions

charges

production

adjustments

production or charge

(credit or debit)

payment or collection

(credit or debit)

credit card transactions

credit memo

current balance

day sheet

disbursements

binder checkbooks

credit card

checkbook register

payroll stub checks

embezzlement

end-of-day (EOD) procedures

end-of-month (EOM) procedures

end-of-year (EOY) procedures

first in, first out (FIFO)

holdback (discount)

monthly ledger

negative account balance

office credit card

packing slip

peg board

petty cash

positive account balance

posting

previous balance

reconciling the bank statement

routing slip

shipping invoice

specific allocation

statement

walkout statements

third-party carriers

transaction history

Every business must have a system for recording all the business transactions that occur each day. A dental office is no exception. It is a business. The compilations of those financial transactions are the “books” of the practice. Most dentists delegate part of the bookkeeping function to staff members, professional bookkeepers, or accountants. However, understanding office bookkeeping is important for several reasons. When a dentist is starting practice, he or she needs to establish a bookkeeping system that provides accurate information that it can be used to improve the practice. Having other people do these functions can be expensive; until a practice has grown, a dentist may decide to keep his or her own books to decrease expenses. Finally, a dentist needs to understand bookkeeping systems so that he or she can review them regularly to assure their accuracy. Embezzlement is a sad but all-too-frequent occurrence in offices where the dentist trusted staff members and did not adequately oversee the bookkeeping function.

A dentist needs to keep books of practice income or charges to patients for services that are done. Some patients will pay on the day services are rendered; other payments will arrive in the mail. Besides these routine transactions, dentists will need to record other transactions from time to time (e.g., no fee, a reduced fee, write-offs). Transaction records will give a dentist information about each patient’s status and overall information about the financial condition of the practice. The dentist also needs a series of “books” that account for expenditures or the money that goes out of the office. This system should keep a running tally of how much money is available, who the dentist owes money to, and the categories of spending for management information and tax reporting purposes. Finally, the dentist will need to combine the income and expense information into a series of books for tax-reporting and management analysis. The dentist will work with an accountant, tax expert, or management consultant to use this information to improve practice performance and to reduce tax burden.

Fortunately, computerized systems have become the norm for dental office patient accounting. These systems replace the physical books of paper systems with computerized databases. The functions in these two types of systems are similar. The dentist still needs to know the terminology and understand how to record items so that he or she can use the system effectively. If the dentist simply turns over the entire accounting function to a staff member without adequate oversight on his or her part, the dentist is inviting the problems of errors and embezzlement. Each of the major computer systems has a report function built into their software. The systems can print out more reports than a dentist can likely use. The problem is deciding which of these reports is useful. The chapter on financial analysis and control describes the data that needed. The computer program can then deliver the data for a dentist’s use. The price and power of these systems make them cost effective for even the individual practitioner. The dentist should use an established computer system rather than trying to develop his or her own. Unless computer programming is a hobby and the dentist wants to spend his or her recreational hours writing computer programs, time can be better spent working in and developing the office.

Cash and checks

Insurance payments

Credit card payments

Who Owes Money

Patient accounts and receivables

Third-party accounts and receivable

Recording Expenses

Expenses by categories

Tax purposes

Management purposes

Checkbook balance

Dental offices have three primary office accounting functions (Box 21.1). The first is to record and account for money that is collected from patients, insurance companies, or others for the services provided. Secondly, the dentist must also track those who do not pay at the time of service, instead owing for all or part of the fee for the service. The dentist accomplishes both through the office management system (e.g., Eaglesoft, Dentrix, Softdent). The final function is to record the payments that are made to others for material and services that are used in the office (e.g., lab services, supplies, payroll). The dentist generally accomplishes this through a readily available commercial program, such as Quick Books. (Some management programs have primitive checkbooks built into them, but the common commercial programs are so powerful and easy to use that most practitioners use them.)

The system described is for patient financial records, not treatment records. These are two separate issues and a dentist will have two separate systems for them. A computer program may cross-link patient charts (for treatment histories) and accounts (for financial histories), but they serve two different functions.

Most service industry businesses (such as dental practices) elect to use “cash basis” accounting. (The other method “accrual basis” is used more in larger and manufacturing businesses.) When using cash-based accounting, income is recognized when it is received (i.e., when the check crosses the receptionist’s desk) and an expense is recorded when it is paid (i.e., when the check is written). A dentist will use the cash basis for both income and expenses. (This does not mean that a dentist only accepts cash payment, but that all transactions are considered like a cash transaction, whether it is cash, check, credit card, or other form of payment.)

Accounting for Income

Businesses that have many cash transactions use a simple cash register to record their daily transactions. Dental offices do not have the number of cash transactions that a fast-food outlet or retail store has, so the dental office will have a different method of recording or registering payments.

Purposes of Income Accounting Systems

Generally, any income accounting system used in the dental office serves five main purposes.

Office Communications

It is a method of communication between the front office and the production areas of the office. The receptionist needs to inform the production area assistants who will be coming and what procedures for which to prepare. After the visit, the doctor, assistants, or hygienist inform the front office personnel what procedures they did and what the plan is for the next anticipated visit (if any). Many dentists do this in person by walking the patient to the front desk and communicating verbally with the receptionist and patient. Others prefer a more efficient written method. If a dentist saves 1 minute per patient and sees 20 patients a day, he or she can either see an addition patient in the time saved (making additional income) or leave the office 20 minutes earlier. Either way, the dentist wins.

At the beginning of the day, the receptionist should provide copies of the day’s schedule in the operatory area (or each operatory) and in the sterilization area. The receptionist then prints a “routing slip” for each patient and places them in the sterilization area. This routing slip specifies the procedure to be done and often other information such as balance due and medical history alerts. Through this communication, the assistants can prepare appropriate instruments and trays for the given procedure for each patient. Routing slips are generally then placed with the tray and taken into the operatory. At the completion of the visit, the office staff or doctor notes on the routing slip what procedures they did and variation from the usual fee (if any). (Offices with networked computer systems often provide this information directly in the sterilization area and operatories, saving time, paper, and possible error.)

Documentation for Patients

An income accounting system provides a receipt to patients, showing the procedures billed today, evidence of any payment received, and their new balance. When dentists enter a procedure onto a patient’s account, accountants say that they have “posted” it to the account. The receptionist completes the receipt after posting the procedures and asking for (and hopefully gaining) payment from the patient for the new current balance (previous balance + charges – adjustments). The receptionist then prints a “walk out statement” for the patient that records this information as he or she walks out of the office.

Insurance Billing

An income accounting system provides information for third-party carriers (insurance companies) for billing and payment purposes. The more quickly accurate information is sent to them, the more quickly the dentist or the patient will receive reimbursement. The dental office may transmit this information to the insurer either through a mailed paper form or electronically through the Internet.

Transaction History

An accounting information system gives a listing of the transaction history (charges, adjustments, and payments) for each patient within the account. The account is the billing unit. The dentist sends one bill to the account guarantor of each account because they are responsible or have guaranteed to pay the account. Each account may contain one or many patients. For example, the father may be the guarantor for an account that contains the spouse and their five children. Or in a divorce situation, the father may be the guarantor for an account in which the child is the only patient on that account. The mother may have custody of the child, but the father is responsible for paying for health care for the child. If the mother is also a patient of the practice, she may be her own account guarantor and the only patient on that account. In a case such as this, the dentist sends the child’s bill to father but sends the mother’s bill to her.

The account or account ledger is the history of all the financial transactions for the account. The current balance is the amount that the guarantor presently owes the dentist for all transactions on the account. A positive account balance says that the guarantor owes the dentist. An account may show a negative account balance if there has been an overpayment. Generally this occurs when third-party payers overpay, or a dentist changes treatment planned procedures, which have already been initiated. (For example, the endodontic procedure that a dentist initiates changes to a less-expensive extraction, although the patient had already paid for the endodontic procedure.) In these cases, the dentist may write either the patient a check for the overpayment, or if the patient desires, the dentist can retain the patient portion of the negative balance to credit it toward future work. Insurance companies will always want the check for a negative balance.

Daily Transaction Journal

Finally, the accounting information system provides a day sheet or a record of each day’s transactions for the practice (and each practitioner, if a multipractitioner office) that summarizes the charges made, payments received, and any adjustments made. The computer program accumulates the day’s transactions to form a monthly ledger. The program then accumulates monthly ledgers into an annual report. Some dentists rely on their computer backup procedure to ensure that their records are complete. Others print out a copy of the day sheet and keep it in a binder as an additional data backup procedure.

Components of Accounting Systems

Computerized accounting systems are composed of a series of related databases. Databases are computer programs, which save large amounts of information concerning a specific item, and then allow the program to relate that information to other, similar cases. The common databases used by these systems include account information, patient information, third-party database, procedure database, practice history database, and specific databases.

Account information defines each account and the guarantor for each account. The account information relates each patient associated with the account, but the program stores the information about each patient in a different location. Generally the program stores transaction histories with each account.

Patient information defines the patient elements (e.g., name, address, age, etc.) and ties them to an account.

Third-party database establishes the third-party carriers, their addresses, and, generally what each plan pays for each procedure.

The procedure database defines the procedures that dentist do, usually by specifying ADA code procedure numbers. This file also includes the normal fee for each procedure and the fee allowed by each insurance plan.

A practice history database holds daily and monthly activity reports (day sheets and monthly summaries).

Programs include specific databases that store information for the individual program. Examples include dunning messages (little notes that appear on patients’ bills), schedule databases, prescription databases, medical history messages, and many other types of information.

These computer programs use each database as needed, pick up the information that they require from that database and then move to the next database, adding required information. For example, if a dentist does a two-surface alloy on a patient who has insurance, the program first identifies the patient from the patient database. It then relates that patient to the account, checking to see the balance of the account. It finds the insurance information from the third-party database, which tells the main program how much the dentist expects the third-party carrier to pay for this specific procedure. It checks the procedure code file to decide how much the dentist normally charges for this procedure. The main program then calculates the amount that the patient should pay, enters any payments made, and saves that information in the updated transaction file for the patient and on the day sheet for the practice.

Accounting Terminology

A charge is the dollar amount that a dentist requires to do the service. It is the same as his or her production figure. Payments may come from the account guarantor or patient as cash, check, or charge card or may come in the mail from third-party payers, such as insurance companies or employers. Adjustments are the amounts for which a dentist decides not to bill. This may be as a result of the patient being a friend or family member or may be required by a managed care insurance plan. A production (or charge) adjustment is a change in the amount of a patient’s account as a result of changes in procedures done. A payment (or collection) adjustment is a change in how much money the dentist expects to collect from the patient. Either production or collection adjustments can be credits to the account (decreases the balance due) or debits from the account (increases the balance due.) In the previous example, the dentist had initiated and charged an endodontic procedure but then changed this to an extraction. The dentist has a charge credit (negating part of the endodontic procedure) and a new charge for the extraction. If a dentist does a procedure on a family member or a managed care patient, “writing off” 50 percent of the amount due, the dentist enters a payment credit because the production remains unchanged. When the computer calculates the new “current balance,” it uses the formula: Previous Balance + Charges – Payment – Adjustment = Current Balance (Box 21.2).

A credit is an accounting entry that decreases the account balance. A debit is an entry that increases the account balance. Adjustments may either be related to production (or charge) or else to payment (or collection) adjustments (Table 21.2). Either type may be a credit or debit to the account. The dentist wants to keep the types separate so that he or she can keep an accurate tally of office production and collections. The dentist also wants to have a separate payment adjustment for each type (e.g., Delta Dental, Aetna) so that he or she can track the discounts for each plan. This way the dentist can calculate the overall reimbursement rate for the different plans. The chapter on dental insurance discusses how to do this.

Table 21.2 Types of Adjustments

| Credit (Decreases Balance) | Debit (Increases Balance) | |

| Production (Charge) |

Entry error Redo a procedure |

Entry error |

| Payment (Collection) |

Cash courtesy Bad debt write-off Patient refund Insurance refund |

Insurance did not pay full amount |

Income Accounting System Procedures

Patient Encounter Procedures

Specific patient encounter procedures vary by office and the amount and use of technology in the office. The essentials remain constant.

At the beginning of the day, the people working in the sterilization area and each operatory need to know who is coming in and what procedure is planned at the visit so that trays, equipment, and operatories can be set up appropriately. There are three common methods. If the office uses a paper schedule system, the receptionist makes a photocopy of the day’s schedule and posts it in the sterilization area and each operatory. (No one should display them for patient privacy [HIPPA] security.) If the office uses computerized scheduling with computers in each area, then the staff can pull up the day’s schedule on the computer system or print out a copy of the day’s schedule. Finally, many offices print out a routing slip for each patient planned for the day. Sterilization areas use the routing slip to set up trays. They then place the slip with the tray that goes to the operatory.

Patient Walkout Procedures

Once the dentist does the dental procedure, he or she needs to tell the front office what he or she did for charge purposes and what is planned at the next for scheduling purposes. If each operatory has a computer station, many offices have the staff directly enter the procedure on the patient’s ledger. By the time the patient arrives at the front desk to leave, the receptionist then has the patient’s bill ready, waiting for payment. If an office uses a routing slip, then staff enters the procedures for the day and plans for the next appointment on the slip. The patient then walks the routing slip to the front desk, where the receptionist enters information on the patient’s ledger and asks for payment, and schedules the next appointment. When the patient returns to the reception desk, the receptionist enters the day’s procedures, determining the total amount owed and an estimate of insurance coverage (if any). The receptionist should then ask the patient for payment, entering any payments into the system and then he or she should print a walk out statement, which details the day’s procedures, charges and payments, and an account summary. Finally, if the office uses mailed insurance forms, the receptionist should then printout an insurance form of the day’s procedures to put in the mail.

End-of-Day (EOD) Procedures

Day sheets should be closed and “proofed” each day. Proofing means that the dentist verifies or proves the correctness of the entries and the mathematics. Proofing is important to ensure the accuracy of the accounting and to guard against the possibility of staff embezzlement. Day-end proofing includes proof of posting, accounts receivable proof and control, cash control, and bank deposit verification. Proof of posting verifies that staff members have entered the day’s transactions correctly, that they have accounted for adjustments properly, and that they have credited payments correctly. Accounts receivable proofing verifies the accuracy of the total accounts receivable and keeps a running tally of the amount. Cash control checks that staff has accounted for all cash transactions. This cash may be as patient cash payments or in “petty cash.” The bank deposit verification assures that the staff have included all payments in the bank deposit for the day. EOD checking takes just a couple of minutes each day, but it is simply expected business practice on the part of the dentist.

The dentist should be sure to close the day sheet at the end of the day’s operation and not later. If staff members have made entry errors, they need to address them quickly so that their effect will not multiply throughout subsequent days. Computer systems will not make mathematical errors, but data entry errors are still a problem. (The receptionist may have entered a collection credit instead of a collection debit.) The receptionist or office manager will generally make all entries. The dentist should verify all entries and the proofing procedures each day. Again, this is not paranoia, simply sound business practice.

By the end of the day, several procedures must be completed.

If a patient pays in cash, the transaction should appear in the payment section of the day sheet. Even if a patient has a “no charge” visit, the receptionist should give him or her a walk out statement to:

Verify their previous balance, if any.

Ask for payment.

Ensure all patient cash transaction have been recorded.

End-of-Month (EOM) Procedures

The office needs to do a couple of additional procedures at the end of each month. Again, management computer systems have built in procedures that do these functions.

End-of-Year (EOY) Procedures

EOY procedures are similar to end of month, except that they account for the entire year. The system will guide the user through the procedure.

Types of Patient Payments

Patients should be encouraged to make payment when the procedure is completed. This may be in the form of cash, check, or credit card. The receptionist informs the patients of the total amount owed. He or she then receives the payment and enters the payment into the computer system and prints a walkout statement. After the receptionist gives this to the patient for verification, he or she stamps the back of the check with a bank deposit stamp and places it and any cash in a secure area of the desk.

Cash

The dentist should deposit all money taken into the office in the office bank account. If he or she takes any cash from patient payments for personal use, the dentist should be sure to use the accounting system totals for income tax determination, rather than the checkbook or bank statement. Dentists face a real temptation to pocket cash money without entering it into the accounting system. People may know others who do it and get away with it. However, the risks are not worth the little extra income (income tax savings).

Note: It is not a good idea to take cash money for personal use without reporting it to the IRS as taxable income. The IRS takes a dim view of people who intentionally do not report income. If a dentist does this, several negative things may happen:

Patient Payment by Personal Check

Many patients pay with personal checks. They should make out the check to the dentist’s name or the name of the office or practice (if it is different). The front office should staff stamp each check (on the back in the “endorsements” section) when it is received. This stamp has “For deposit only” with the bank and account number. (Banks will generally send businesses these stamps, although there may be a small fee.) That way, if someone steals a check, he or she can not cash it; it can only deposited into the dentist’s account.

Patient Payments by Credit Card

Many offices allow and encourage patients to make payment by credit card. From an accounting perspective, these payments are no different from any other. These should be included a payment on the day sheet and patient accounts.

The dentist will set up a merchant account with a bank to oversee credit card transactions. (Banks offer different rates, fees, and options, so the dentist should shop around.) The overseeing bank may hold these payments in a separate account or may deposit them directly in to office checking account. When the dentist transfers this money to the checking account, the dentist does not have to report it. He or she has already counted it as income when it was entered into the accounting system. Other banks will directly deposit the credit card transaction amount into the checking account the day it occurs. The bank will then summarize the transactions in an EOM statement.

Credit cards charge a fee for each transaction and often a monthly service fee. (See the chapter on credit and collection procedures for a detailed discussion.) The banks call this a “holdback” or “discount.” The dentist does not need to enter each transaction fee into the checkbook but rather the entire monthly discount amount. It should be entered as a bank expense in the checkbook.

Accounting for Traditional Insurance Payments

If a patient has dental insurance that covers all or part of the fee, then the accounting becomes a bit more complex than a simple cash transaction. The big question is whether or not the dentist accepts “assignment of benefits.” This means that the insurer will send (assign) the benefit (payment) directly to the practice instead of the patient. The chapter on credit and collection policies discusses this in more detail.

If the dentist does not accept assignment of benefits, the accounting is easy. The dentist should charge the patient (actually the account) the full fee and collect as fee for service. The dentist then prints a completed insurance form for the patient to submit, and the patient is responsible for getting reimbursed from the insurer.

If the dentist does accept assignment of benefits, then he or she collects from the patient only the portion that the insurer does not pay. There are two options here. First, the dentist can submit the insurance form to the insurer. The reimbursement will be sent to the dentist. The dentist waits until the insurance “clears” and then charges the patient the difference. The second option is to estimate (through the computer system) what the insurer will pay and charge the patient their expected amount immediately (at time of service). When the insurance company sends payment for its portion, the dentist reconciles his or her estimate with the actual payment. If there is a difference, the dentist either charges or reimburses the difference, depending on whether the total payments are too large or too small. The claim should be closed in the computer system so that it will not continue to track the claim as open (unpaid). The second option speeds cash flow through the practice, but it may require some adjustments after the insurance clears. The dentist also needs to be sure to keep accurate and up-to-date information on all the plans in the computer.

With any of these systems, the dentist should get a pretreatment estimate of benefits from the insurer, especially for large cases or insurance plans with which the dentist is not familiar. The insurer will send an explanation of benefits (EOB) to dentist and the patient. This estimates the patient’s coverage (what the insurer will pay for the procedures) that the dentist has submitted for this patient. It is not a payment or even a contract for payment. It is a good faith estimate of what the insurance company will pay. It can (and occasionally does) change from the time the dentist receives the estimate and submits the claim for reimbursement. This does not allow or disallow treatment. That is between the dentist and the patient. The insurance simply pays (or not) for certain procedures, according to the contract with the patient or employer. The pretreatment estimate defines this payment so that no one is surprised.

Insurers will often send one check for payment for services done for several patients. These “bulk payments” will have a form (explanation of payments) with them that details the patient payments included, what procedures the payments cover, and the amount of each payment. When the dentist receives these bulk payments, he or she should be sure to allocate them to the proper procedures on the correct patients.

Accountings for Managed Care Payments

If a dentist participates in a managed care program, he or she will have signed a contract agreeing to the terms of the program, one of which is a reduced fee for procedures. Two options exist for these payments, depending on the specific program(s) with which the dentist participates. In one, the dentist charges and collects from the patient a contractually agreed price for each service. In this case, the dentist enters the full fee value as the charge and then adds a collection adjustment of the difference between the full fee value and the contractually agreed fee. This is listed as a “managed care adjustment” or discount. In the second method, the dentist submits the full fee value to the managed care insurer like a traditional insurance plan. The managed care insurer then sends payment along with an explanation of payment that details how much it reimburses and how much (if anything) the dentist may charge the patient. The difference between the full fee and the total payments (from the insurer and patient, if any) is the managed care adjustment. The chapter on third-party plans describes the financial impact of managed care participation on the dental practice.

Tracking Who Owes Money (Accounts Receivable)

Immediate payments are easy to account for on the day sheet. A bigger problem comes when patients do not pay immediately or have a third-party that pays all or part of the bill. The dentist needs to track the amounts that patients and insurers owe so that the dentist can be sure that he or she is paid properly. (See the chapter on credit and collection policies for a discussion of how to set financial policies for the office.)

All management computer systems have a method for tracking accounts receivable. These are generally called account aging reports. These reports categorize accounts by the time since the patient made the last payment. The generally accepted categories are 30, 60, 90, and 120 days. So an account that falls into the 60-day category has not had a payment made in at least 60 days and possibly as many as 89 days.

Simply printing the report does not solve any problem. The dentist has to use the information on the report. This means calling patients, writing letters, or denying future appointments until the patient brings the balance up to date. The older the account, the more difficult it is to collect. So the real value of these reports is to prevent problems by identifying slow payers early so that they can be encouraged to pay what they owe.

For patients who have insurance, there are two theories for determining aging of accounts. (Most dental office software will let a dentist choose which method to use.) The dentist can “start the clock” for payments when the procedure is billed or start it when the insurance has cleared and th dentist is certain what the patient’s portion of the bill is. If a dentist uses the first method, he or she needs to have good information about the patient’s insurance plan so that the patient’s portion can be accurately estimated. This becomes less of a problem with plans that are common in the dental office; more of a problem with seldom-used plans.

The dentist also needs to keep track of insurance forms and pretreatment estimates that he or she has submitted to insurance companies. If the dentist does not get a response from the insurance within 30 days (some offices use 2 weeks) then the dentist (or staff) should follow up with a telephone call to find out what the problem is. Insurance companies are not usually in a hurry to pay out money, so claims and pretreatment estimates may sit on someone’s desk if they have a question. The dentist’s computer program will track “open” (unpaid) claims and pretreatment estimates that insurers have not returned; he or she should use this feature regularly.

Multipractitioner Offices

Accounting for income becomes more complex in multipractitioner offices. The problem becomes allocating charges and payments to particular providers, rather than the office as a whole. (If the providers are all on salary or other fixed compensation, then there is no need for allocation; simply tally the office totals no matter who provided the service.) There are two common methods of allocating payment to providers, first in, first out (FIFO) and specific. FIFO is an accounting term that means that the payments go to the first procedure completed on the transaction history. Specific allocation states that the dentist will credit the payment to the nearest specific procedure.

For example, Dr. Alpha sees Mrs. Jones and does $300 worth of dental procedures. The next visit, Dr. Baker does a $400 procedure, which requires a $200 down payment. Mrs. Jones pays $300. Who gets credit for the $300 payment? The FIFO procedure says that Dr. Alpha gets credited. Because those procedures were the “first in” the account, they should be the “first out” as well. (This says that the well is filled from the bottom up.) The specific method says to credit Dr. Baker because the requirement for the down payment takes precedence over the age of the receivable. Either way works; the dentist needs to be sure to list in advance which method the office will use. (The FIFO method is more common.)

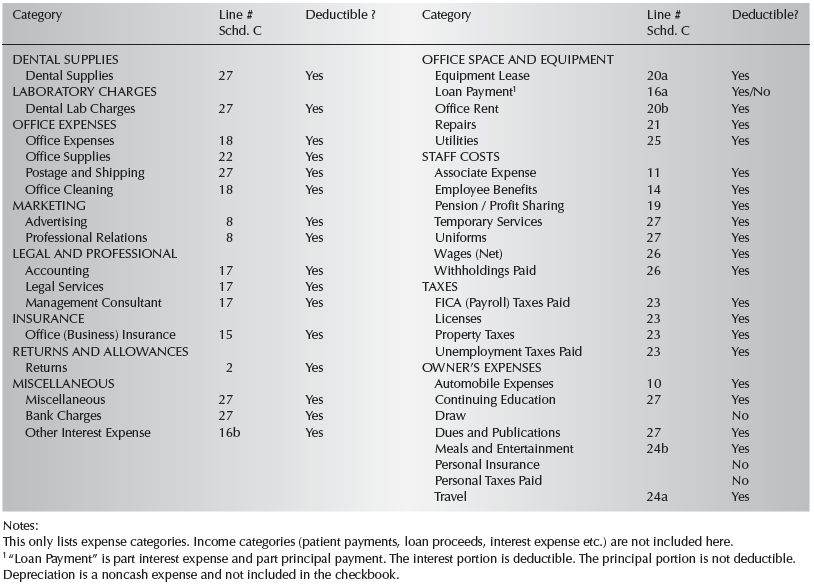

Recording Expenses: Payments to Others

The dentist also will need a system to record and categorize expenditures for the office. He or she needs this information for two purposes: to know how much cash is in the account and to record expenses for tax and management purposes. Most dentists have two methods for paying office expenses: a credit card and checkbook.

Checkbook Systems

The office checkbook is the system for managing cash in the practice. The dentist should have two checking accounts: one for the office that contains only office expenditures and another personal account that has only personal expenditures. This way, the accounting becomes much easier because the dentist does not need to decide, after the fact, if an item is an office expense or not. All checks written from the office account are business expenses. Be sure that the categories that are established for the checkbook register are the same ones used for tax reports and management information. That way, the entries will not have to be recategorized when the reports are run. (Table 21.3 gives an example of the categories.)

Dentists deposit all income (cash payments, personal checks received from patients, insurance checks, and credit card payments) into the office checking account. (The total amount of daily deposit should be the same as the daily receipts on the computer system.) Dentists then make all office payments from the checkbook and pay the office credit card with a check from the office checking account. If the dentist borrows money, it adds to the checkbook balance, but it is not considered income.

The check register is the mechanism for recording and allocating office costs. Registers may be paper products (they are available from any office supply house) or they may be part of a computerized check system. Check registers identify checks issued for the month and allow the dentist to categorize each expenditure for tax reporting and business management purposes. The purpose of the register is not to keep a running tally or balance of the checking account. The dentist should do that in the checkbook on the check stubs. Instead, the register allocates or categorizes expenses into categories. Summarize the categories for the month and “post” them to an annual report.

The annual report is a summary of all office expenses for the year, broken down by category. These categories are the same as on the checkbook register. The annual report is what the dentist takes to the accountant for processing of taxes. If a dentist has done a good job in these bookkeeping chores, he or she will save hundreds or thousands of dollars in tax preparation fees.

Types of Checkbooks

Binder Checkbooks

Some dentists have checkbooks that fit into three-ring binders, which the bank has provided. The least expensive method is to get the checkbook from the bank and then purchase a good register from an office supply company. Bank checks come in two styles. If a dentist processes his or her own payroll, he or she should get the type called “payroll stub checks” that have an extra section for recording tax withholdings on employees’ checks. The dentist will keep meticulous records of employee withholdings on a separate payroll record. Nevertheless, it is important that employees see the total amount of their pay (gross), and all the money that various taxing agencies require that employers withhold and pay for them. Although this will not necessarily make employees happier about their pay level, the lack of this information can cause confusion and dissatisfaction.

Table 21.3 Listing of Accounts for Office Checkbook

Computer Checking Systems

Many dental office management programs have check writing and register elements included. Most dentists use commercially available accounting systems such as Quicken/QuickBooks. These systems can print the physical check itself, keep an accurate register, determine staff pay and withholdings, produce financial statements, and transfer funds electronically. They are the most effective method available today for tracking expenses in the office. They all operate using the same principles and nomenclature as traditional checkbook systems.

Electronic Checks (E-Banking)

Many banks allow and encourage patrons to use e/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses