Chapter 2

Understanding Key Moments in Child Development

Developmental psychologists examine changes in physical, cognitive, and social/emotional development across the lifespan. Understanding how changes in each of these domains occurs allows researchers and practitioners to predict how individuals of different ages and abilities will react and behave in familiar and novel situations. This chapter will summarize changes that occur in each of the physical, cognitive and social/emotional domains in typically developing children, and will provide insight regarding what to expect from children and adolescents. One caveat before reading further is that the developmental sequences summarized here represent “averages,” or estimates of children’s abilities, expectations and experiences at any given point in development. Individual differences among children are great, and even within an individual child there may be variation in development. For example, while language skills may be high, physical development may lag behind peers of the same age. Thus, we must be careful not to overgeneralize based on a single observation, nor should we expect all children to conform to a single “right” pattern of development.

The information provided here explains how development progresses and identifies when major developmental changes typically are observed with the understanding that practitioners working with children must be ready to shift their expectations depending on their encounters with each individual child. Much of the information in this chapter deals with early childhood and presents information that often is not found in dental writings. However, more and more importance is being placed upon knowledge about the early years and how this contributes to understanding future development.

Why Very Early Development is Critically Important

Before exploring the lives of children, it is important to first think of their very earliest beginnings. An incredible amount of development occurs prior to birth as well as in the first few years of life, and the outcomes of these early experiences can have a lasting legacy. For this reason, knowing a little about a child’s early development is important in assessing clinical issues about the child. In addition, having this information reinforces the important role practitioners can play in assisting to-be parents through pregnancy and early infancy. Throughout this section, both nature (i.e., biological/genetic) and nurture (i.e., environmental) issues are highlighted, as both of these factors interact to shape the individual. By adopting this interactionist perspective, it becomes clear why all practitioners should take an active role in providing the best start for young lives.

Setting Good Foundations: Prenatal and Early Development

Advances in technology have allowed us to see that critical brain development occurs much earlier than we originally imagined. Indeed, the vast majority of the neurons an individual will ever have are formed by the end of the second trimester of pregnancy (Kolb and Fantie 1989; Rakic 1991). This is followed by the “brain growth spurt” between the last three prenatal months to the end of an infant’s second year, when more than half of an individual’s adult brain weight is achieved (Glaser 2000). During the brain growth spurt, more neurons are produced and it has been suggested that this abundance of neurons prepares the infant to face the myriad of possible sensory and motor experiences that could occur (Greenough et al. 1987: 2002). Since no individual experiences every possible form of stimulation, unnecessary neurons fail to thrive or serve as a reserve for injuries or new skill development (Elkind 2001; Huttenlocher 1994; Janowsky and Finlay 1986). In addition, neurons that successfully interconnect with each other crowd out those that do not. Both maturational unfolding and early experience, therefore, are important determinants of brain growth (Greenough et al. 1987; Johnson 1998, 2005; Thompson and Nelson 2001).

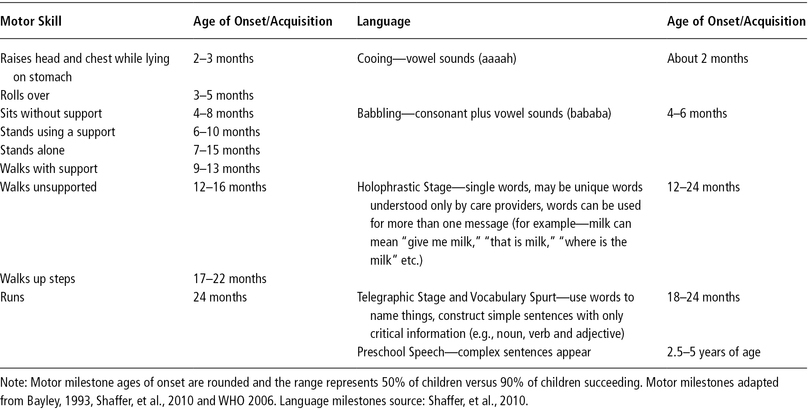

Physical growth also occurs at a rapid pace prenatally, during infancy, and through the early childhood years. The pace then tapers until adolescence when it increases again. With some exceptions, growth tends to follow both a cephalocaudal (i.e., from head to toe) and proximodistal (i.e., from the center of the body outward) pattern (Kohler and Rigby 2003). For example, prenatally, the head grows much faster than any other body part–so much so that at birth, infant head sizes are approximately 70% of their later adult head size (Shaffer et al. 2010). This growth in head size is followed by quick growth in the trunk area over the first year, which is then followed by rapid growth in leg length until adolescence, when both the trunk and legs lengthen. Proximodistal growth is also observed prenatally as the chest and internal organs form, followed by the arms and legs, and then the hands and feet. The growth of arms and legs outpaces the growth of hands and feet until puberty, when the hands and feet become the first body parts to reach adult proportions, followed by the arms and legs and, finally, the trunk (Tanner 1990). Muscular development also proceeds in cephalocaudal and proximodistal directions, with muscles in the head and neck maturing before those in the trunk and limbs. This pattern of growth can be used to explain how children acquire some motor movements before others. For example, head control comes in early while precise pincer grasps come in quite a bit later. Major motor milestones follow a fairly constant pattern. For a quick review of actions and expected trajectories see Table 2-1. It is important to keep in mind, however, that although the pattern of change tends to be similar across individuals, there is considerable variation in the acquisition of skills (resulting from differences in the timing of growth spurts, the amount of growth that takes place, and stimulation from the environment). As long as the skill is attained within the expected range, there is no particular advantage for earlier versus later acquisition.

While enriching environments can promote healthy growth, teratogens (e.g., drugs, diseases, environmental hazards such as X-rays or toxic waste) are agents in the environment that can cause birth defects (including facial and dental deformities), intellectual deficits, behavioral problems and death (Kopp and Kaler 1989, Mattson and Riley 2000). Many teratogens do the most harm during the first trimester, when there are critical periods where certain body structures develop. Other teratogens are particularly problematic later in pregnancy or during the early years. In order to ensure steady, healthy growth of brain and body, practitioners, parents, and researchers need to be aware of, and reduce, the presence of teratogens. One goal within the concept of The Dental Home (see Chapter Five) is to offer supportive instruction that complements healthy lifestyle choices for potential parents. It can provide protection against harm and promote healthy growth.

Table 2-1. Developmental milestones in movement and communication.

Coming Prepared for Action: Infants and Young Children

Refinements in physical development prepare infants and children for increased mobility. Mobility is one important foundation for encouraging exploration. For example, once infants attain head and neck control they can orient themselves toward interesting things to watch or hear. Rolling, sitting, standing, and walking (milestones shown in Table 2-1), continue to expand access to intriguing, novel, and familiar stimuli that fill children’s worlds. Indeed, infants are not the “helpless,” dependent, and passive participants in the world that we viewed them as in the past. We now know that infants arrive as active, engaged learners equipped with an impressive range of reflexes and sensory skills that allow them to respond to the vast array of stimuli that the world presents.

Among their repertoire of early reflexes are sucking, swallowing, coughing, and blinking, which serve important survival and protective functions. Similarly, other, less well-known reflexes such as the rooting reflex–which occurs when an infant is stroked on the cheek, resulting in the infant opening its mouth and preparing to latch to a nipple–also provide infants with skills to help them survive. In some cases, problems with reflexes such as sucking may lead to referral to a dentist. For example, mothers may be referred to a lactation consultant, who, in turn, sometimes calls upon a pediatric dentist to assess the need for a lingual frenectomy. Thus pediatric dentists need to be familiar with a newborn’s features, development, and characteristics since they may be referred infants shortly following their birth for examination.

Newborns also demonstrate reflexes that appear to serve no apparent function. For example, the Palmar grasp involves infants closing their hand around any object placed in the palm. Although parents and other care providers are often delighted when it appears that the infant is “holding” their finger, reflexes such as the Palmar grasp are believed to be vestiges from our evolutionary past. The presence of these reflexes at birth, as well as their disappearance in the first few months (when reflexive behaviors come under the voluntary control of higher brain centers), are early indicators for assessing development of the nervous system.

In terms of sensory readiness to explore the world, the five senses, although not all fully developed, are functional at birth. Newborns even have preferences for certain odors, tastes, sounds, and visual configurations. For example, infants prefer sweet tastes and are able to differentiate between salty, bitter, and sour solutions. They will also turn their head in the direction of a sound, and most show a preference for female voices. Early experiments comparing infants’ preferences for their mothers’ voices or faces compared to voices or faces of unfamiliar females demonstrated that, within the first few days of life, infants showed a preference for the familiar voice and face (DeCasper and Fifer, 1980; Field et al. 1984). Although vision is the least-developed sense (with acuity being about 20/600), newborns can still see all or almost all of the colors adults see (Brown, 1990; Franklin, et al. 2005). Newborns are also responsive to touch and sensitive to pain (Porter et al. 1988).

Cognitive Development: Learning, Thinking and Memory

Cognitive development starts early and progresses quickly as children are exposed to rich and stimulating learning environments. Interesting environments for young children can include both novel and familiar materials. Novel materials and books allow children an opportunity to expand their experiences, acquire new skills, and map learned skills to new contexts. Familiar materials, especially those that children can use in many ways (such as containers or blocks that can be stacked, be used to build things, or serve other purposes such as being tools, musical instruments, or even transport devices for other toys, etc.), also allow children to experiment and evolve their play just as well-loved books can allow them to demonstrate their increasing comprehension, letter-recognition, and other reading skills. Cognitive development, then, is influenced greatly by children’s experiences, the information they are given and the way in which they are encouraged to explore new information and events.

Exactly how does cognitive development take place? Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development embraced the notion of children as active, engaged learners who try to understand the world and experiences they encounter (Piaget 1971; Piaget and Inhelder, 1969). In his theory, children pass through four invariant stages of intellectual development with each stage reflecting a qualitative shift in reasoning capabilities. Schemas serve as the underlying cognitive structures that are used to identify and interpret objects, events, and information that infants and children encounter. Infants have very basic schemas that are refined, and replaced with more complex ones as children acquire more skills. Schemas are altered through two complementary processes, called assimilation and accommodation. When we encounter new objects, events, experiences, and information, we first use existing schemas to understand what is going on. If the new experience does not “fit” (i.e., it cannot be assimilated), then the schema must be modified, or a new schema must form to accommodate this new information. For example, when a child encounters a horse for the first time, they might try to understand it in terms of their pet dog and think “this is a very large dog.” However, when they become aware that the horse is quite different from a dog, this initial conceptualization will change and they will now think about dogs and horses in a different way. Piaget believed that within each of his stages there were significant cognitive understandings that children acquire. Once these ways of thinking were achieved, the child would progress to the next stage.

Using the tests that Piaget devised, we can still see infants and children respond in the same way that Piaget observed within each stage. For example, Piaget believed that infants experienced the world through their senses and motor activity with objects in the here and now. This first stage, the sensorimotor, begins at birth and extends to eighteen to twenty-four months. Once objects were no longer in view or available, infants perceived them as no longer there–literally “out of sight” meant “out of mind.”

A critical achievement, then, would be for the infant to be able to represent objects and people mentally, rather than just tangibly. That is, children must come to understand that things exist even when they are not immediately visible or in hand. This understanding of object permanence, at about two years of age, represents the point where Piaget believed they move to the second, or preoperational stage.

Preoperational children (ages two to seven) experience a language explosion, and with that increasing skill they come to use the arbitrary symbol system of language to represent objects and actions. Now words and images can be used to represent things and events. As the ability to represent things increases, there is also an increase in imaginary or symbolic play, where children pretend to be other people, creatures, and objects, and use objects in creative, playful ways. Concomitant with these gains are several limitations. For example, limitations in children’s schemas inhibit their ability to solve some logic problems. That is, children are unable to mentally manipulate all of the “operations” needed to solve some problems (hence the name preoperational).

The inability to solve conservation problems provides a good example. An example of this problem would be to show children a short, fat glass filled with liquid. Then, in full view of the child, an experimenter would pour the liquid from the short, fat glass into a tall, skinny glass and ask the child if the glasses contained more, less, or the same amount of liquid. The answer? Most children report that the tall, skinny glass has more. Children appear to be stymied by the one change–the higher height of the liquid in the tall glass–rather than understanding the constancy of volume across the two glasses. Children make this same mistake with mass and number. When children hone in on one feature, especially a perceptually salient one, to the detriment of taking in all the important variables, they are said to be engaging in centration–a characteristic flaw for this stage–and one that contributes to their failure at conservation. Children also have challenges with reversibility. In the case of the volume problem above, children may not be able to reverse the action and understand that the liquid could be poured back into the short fat glass, which would allow them to see that the volume would remain the same across the two glasses. Centration and irreversibility are two errors that impact children’s problem solving.

Children in this stage are also egocentric in their thinking. Often we interpret the word egocentric as something negative, but in this context it refers to how children “see” or represent the world. Think of children as seeing the world through only their own eyes and through only their own experience. For example, a child might show you an interesting picture he has found in a book. When showing it to you, the child might orient the book toward him rather than you, leaving you with an upside-down image. The child may not seem to understand that you will not be able to see the image well from that upside-down perspective. Egocentrism also shows up in children’s answers to questions. For example, parents might call out to their young child “Where are you?” and get the reply “Here.” The child is not trying to be obstinate or deliberately vague. Instead, the child looks around the environment that he can see and it is obvious to him that “here” is where he is. These cognitive traits for two to seven year old children can have great import when communicating with preoperational children in the dental office.

By Piaget’s third stage (concrete operations) children seven to twelve years of age are able to navigate the problems of preoperational thinking. They can decenter their thinking and focus on more than one dimension of a stimulus at a time. They understand the concepts of reversibility and conservation (although conservation comes in slowly with conservation of mass, for example, preceding conservation of volume). They can also engage in mental seriation (mentally arranging items along some quantifiable dimension such as shortest to tallest) and they are less egocentric. What is the limitation for children in this stage? The label “concrete” describes the most significant limitation. Children can apply logical operations only to concrete problems. Abstract or hypothetical problems are a challenge that is not resolved until children achieve the final stage, formal operations.

Figure 2-1. Allowing children to ’teach’ their favorite stuffed toy or a puppet can make the setting more memorable and more personally relevant for pediatric patients (a). Demonstration dolls are available for this purpose (b). Courtesy of Dr. Ari Kupietzky.

The formal operations (ages eleven to twelve and beyond) stage represents the ability to fully engage in multiple forms of logical thinking. Children can think deductively and inductively. They can generate and test hypotheses, and explore concrete and abstract ideas. This level of thinking, however, is not achieved by all children (or adults) (Kuhn 1984; Siegler 2005).

Applying Piagetian Theory Today

Critics of Piagetian theory argue against the notion of broad invariant stages, instead favoring constant, incremental gains with some areas developing well before others (Bjorklund 2005; Siegler 2000). Many traditional Piagetian tasks are considered too challenging, often requiring more than one skill set simultaneously (for example, requiring both advanced verbal and perceptual skills). For that reason, Piaget is thought to have underestimated the abilities of very young children and infants. However, we continue to adopt Piaget’s understanding of infants and young children as active, curious, and engaged learners, who construct knowledge by generating, testing, and developing theories to explain their world. Understanding children in this way means that we should present environments that intrigue them and give them opportunities to engage in trial and error. Even small changes to our approach to children can make this possible. For instance, some dentists acclimate young children to their practice by letting them see the equipment, and maybe take a “ride” in the chair. If this acclimation was taken one step further by allowing the child to see and test how the chair functions and how other tools work, then the children would be both familiarized and intrigued. Children may be given a dental mirror and shown how it assists the dentist in seeing the teeth from all aspects.

Encouraging them to think about the process without giving them all the answers can engage a child and begin the kind of rapport that is built upon interest and that can sustain engagement with a child. Knowing that pretend play emerges in the preschool to early grade school years tells us that this is a time to use pretend play as a way to connect with children and to convey important skills and knowledge in a manner that is interesting to them. For example, allowing children to pretend to be the dentist. Having them learn important hygiene skills or routines by letting them “teach” their favorite stuffed toy or puppet can make the setting more memorable and more personally relevant for the child. Demonstration dolls are available for this purpose (Figure 2-1). Regardless of age, effective teaching should involve concrete, observable instructions and demonstrations to maximize learning.

More Recent Views on Cognitive Development

More current views on cognitive development typically borrow from the work of Vygotsky or information processing models. Vygotsky (1978) argues that children’s cognitive development is highly tied to sociocultural factors. Children do not learn in a vacuum; instead, their knowledge is shaped by the beliefs, values and tools that surround them as they develop. This cultural context influences not only what they know but how they think. Where Piaget attributed cognitive gains to mechanisms within the child, Vygotsky argues that many of the discoveries and knowledge that a child attains are facilitated through exchanges with a knowledgeable “other.” The other can be a parent, peer, teacher, dentist, or anyone who engages the child and works collaboratively to help bring the child from their current level of knowledge to a higher level. Knowledgeable others can support learning because they can bridge the distance between what the child currently knows and can accomplish on his own, and what the child is capable of acquiring or performing with a little guidance or assistance. The term “zone of proximal development” represents this distance in knowledge. If the distance is too large–that is, too complex–it exceeds the child’s zone of proximal development, the child will not be able to internalize or make sense of the information, and the learning opportunity will be lost. Using Vygosky’s theory as the framework for facilitating practitioner-client interactions requires several key elements. First, practitioners need to know something about the context and culture/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses