Chapter 2

Understanding Endodontic Failure

Aim

To describe the reasons why root canal treatment fails in practice.

Outcome

At the end of this chapter, the practitioner should be able to identify the possible reasons for root canal treatment failure and understand how failure may be converted to success.

Introduction

When failure has occurred or if a periapical lesion does not heal after root canal treatment, there are four possible ways of dealing with the problem:

-

wait, watch and reassess

-

non-surgical retreatment

-

surgical retreatment

-

extraction.

As patients increasingly express a preference for retaining their natural dentition, non-surgical or surgical retreatment offers the patient another chance of saving their root treated tooth. The first practical step in managing endodontic failure is to identify the cause. Only then is it possible to retreat a tooth with confidence. Unless the cause of failure is properly addressed, there is a risk of perpetuating or compounding the problem.

Possible Causes of Failure

Persistent Infection

The commonest reason for endodontic failure is infection, caused by the presence of microorganisms and their by-products, inside or outside the root canal system. This may be a result of new infection being introduced or a failure of the original treatment to manage the pre-existing infection.

Intraradicular infection

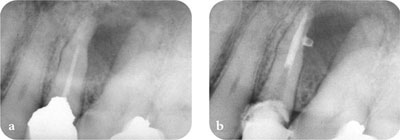

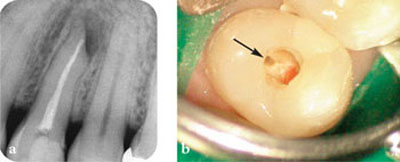

Persistent intraradicular infection occurs most frequently when the original treatment falls short of acceptable technical standards (Fig 2-1a). Cross-sectional surveys from various countries have revealed that, on average, 30% of endodontically treated teeth are associated with periapical radiolucencies and there is a positive correlation with poor technical quality of the root filling. Unfortunately, radiographs, typically taken in a buccolingual direction, rarely tell the whole story. Apparently well-treated cases may have, for example, obvious deficiencies in the third dimension or missed canals (Fig 2-2). Failures associated with technical deficiencies are usually amenable to non-surgical retreatment (Fig 2-1b).

Fig 2-1 Persistent intraradicular infection. (a) Poor technical quality root filling. (b) Managed by non-surgical retreatment.

Fig 2-2 Do not go by looks alone! (a) An apparently well root filled tooth. (b) The missed, untreated palatal canal (arrowed).

Extraradicular infection

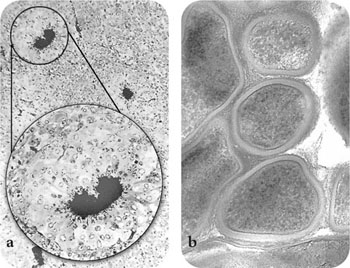

Failures in cases in which a high technical standard of treatment has been attained are more challenging to handle and resolve. Often, it is difficult to identify the reason for this type of failure. Studies have suggested that therapy-resistant cases may be associated with some form of extraradicular recalcitrant infection – an established infection colonising the external root face, forming a biofilm and persisting in periapical tissues. Inaccessible and unresponsive to conventional root canal treatment, the infection also resists the efforts of the host defences. Actinomyces israelii (Fig 2-3) and Propionibacterium propionicum have been reported to be associated with extraradicular infections.

Fig 2-3 A. israelii. (a) Light microscope view showing several colonies, magnified inset shows typical “ray fungus” appearance of actinomycosis. (b) Electron microscope view of ultrastructure, Gram-positive cell walls surrounded by extracellular matrix. (Courtesy of D. Figdor.)

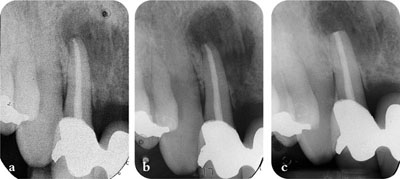

Typically, a radical approach, including a combination of surgical and non-surgical retreatment, may be required to deal with therapy-resistant cases (Fig 2-4). Even then, not all affected teeth can be saved. It should be noted, however, that non-surgical retreatment is almost always justified as a first-line approach for managing failures associated with apparently well root treated teeth (see Chapter 3 and Fig 2-5).

Fig 2-4 Failure due to extraradicular infection. (a) Initial root canal treatment. (b) Six-month review, the periapical radiolucency increased in size. (c) Immediately following combined non-surgical and surgical retreatment. Biopsy report revealed infection caused by A. israelii.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses