Chapter 2

The Meaning of Quality

Aims

This chapter aims to explore the various definitions of quality and to define commonly used words and phrases. It also aims to summarise the valuable contributions made by some of the leading gurus of the quality movement.

Outcome

The reader should be familiar with a number of approaches to quality and the impact of some of the leading proponents in this field and how their views relate to general dental practice.

Introduction

Society has always been concerned about the quality of goods and services provided. Over the ages quality has developed as a discipline; the earliest paradigm of quality relying on the principle of caveat emptor (let the buyer beware) – an approach that placed the responsibility of appraising goods and services firmly with the user. The principles of quality control and total quality management came later with the industrial age, although there is evidence of conformance and control in ancient Rome. However, it was the post-industrial age that saw the development of the modern paradigm which impacts on the world as we see it today.

The American Society for Quality (ASQ) suggests that the term “quality” should not be used as a single term to express a degree of excellence in a comparative sense, nor should it be used in a quantitative sense for technical evaluations. These meanings, it suggests, should be communicated by a qualifying adjective.

A review of the literature suggests that there are numerous definitions of quality – almost as many as there are quality consultants. Hoyer and Hoyer (2001) surmised that these expert definitions of quality fall into two broad categories:

-

Level one quality is a simple matter of producing products or delivering services, the measurable characteristics of which satisfy a fixed set of specifications that are usually numerically defined.

-

Independent of any of their measurable characteristics, level two quality products and services are simply those that satisfy customer expectations for their use or consumption.

This approach is well suited to general dental practice where success is dependent on the delivery of quality care at both these levels.

The meaning and interpretation of quality is contextual; it depends on the nature of the service or product on offer and domain within which it is available. Some examples are listed in Table 2-1 and have certain themes in common, which are:

-

Cost

-

Time

-

Customer experience

-

Defect-free.

| Domain | The consumer view on quality indicators |

| Airlines | Safety, on-time, comfort, low-cost, good on-board food and drink |

| Healthcare | Correct diagnosis, minimum waiting time, safety, security, low cost |

| Restaurant food | Good food, fast delivery, comfortable environment, good atmosphere, polite service |

| Postal services | Fast delivery, reliable, low cost |

| Consumer products | Well made, fit for purpose, defect-free, good value |

| Mobile phone communication | Clear, fast, good coverage, low cost, design |

| Cars | Reliable, defect-free, faster, inclusion of extras, image and reputation of brand |

Definitions

According to the American Institute of Medicine, quality is constituted by: “The degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.” It suggests that:

-

Quality performance and outcomes occur on a continuum, theoretically ranging from unacceptable to excellent.

-

The scope of inquiry is limited to the structure, process, and outcomes of care provided by the healthcare delivery system.

-

Quality may be assessed at multiple different levels.

-

The link between process and outcomes should be established.

-

Research evidence must be used to identify the services that improve health outcomes and in the absence of scientific evidence regarding effectiveness, professional consensus can be used to develop criteria.

In the UK, Donaldson and Muir Gray defined quality in healthcare as: “Doing the right thing, for the right person at the right time and getting it right first time.” It is a definition that suits the practice of dentistry because it emphasises that there is more to quality than the quality of the technical outcome. For example, the quality of the outcome of root canal therapy on an upper molar may be undisputed, but if the root canal therapy has been the result of an incorrect or delayed diagnosis, then the patient has not received the “right thing at the right time”. The root canal therapy may be excellent, but the quality of care may be less than satisfactory.

Another, more generally stated definition (European Committee for Standardization, 1994) holds that: “Quality is the totality of characteristics of an entity that bears on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs.” This allows both provider and patient expectations to be taken into account.

Øvretveit (1992) prefers a broader view, arguing that the scope of the above definition is limited by the fact that it considers the satisfaction of only those who receive the service and ignores those who do not. He defines quality as: “Fully meeting the needs of those who need the service most, at the lowest cost to the organisation, within limits and directives set by higher authorities and purchasers.” Another interpretation introduces variance into the definition. Robert A. Broh observed that: “Quality is the degree of excellence at an acceptable price and the control of variability at an acceptable cost.”

During December 1999, readers of Quality Digest magazine were invited to submit their definitions of quality. Some of those definitions, which reflect the earlier discussions in this chapter, are shown in Table 2-2.

| The meaning of quality |

|

Karl Albrecht of Karl Albrecht International defines quality in two ways:

|

Terminology

Quality Assurance and Quality Improvement

The ASQ states the purpose of quality assurance is to: “Provide adequate confidence that a product or service will satisfy given needs.” Quality assurance helps to identify outliers and usually involves external inspection and some form of accreditation.

Quality assurance is a widely used phrase and there are concerns about what it means. One is that the word “assurance” is a misnomer. Coster and Bue-tow make the point that whilst “quality can be protected and enhanced, it cannot be ensured”. The other is that quality assurance sets minimum standards; this results in compliance to baseline thresholds, but does not instil the ethos of continual quality improvement.

A breach of those thresholds can lead to litigation, complaints and/or disciplinary action by the profession’s regulatory bodies. It can also lead to a culture of “name, blame and shame” – a trend that healthcare organisations are keen to reverse. It is for these reasons that the preferred term amongst pundits is continuous quality improvement.

Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)

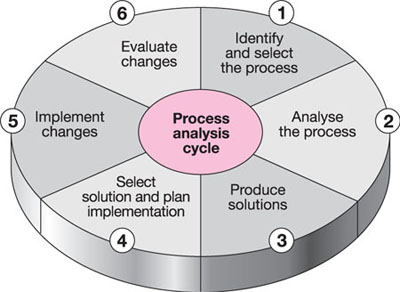

Most problems are found in processes, and CQI aims to improve those processes through small, incremental changes (Fig 2-1). It has been defined as: “An approach to quality management that builds upon traditional quality assurance methods by emphasising the organisation and systems: focuses on ‘process’ rather than the individual; recognises both internal and external ‘customers’; promotes the need for objective data to analyse and improve processes.” (Source: Graham NO. Quality in Healthcare, 1995)

Fig 2-1 Analysing the process.

The key features of CQI are:

-

Success is achieved through meeting the needs of patients.

-

Most problems are found in processes, not in people.

-

CQI does not seek to blame, but rather to improve processes.

-

Unintended variation in processes can lead to unwanted variation in outcomes – this is addressed by reducing or eliminating such unwanted variations.

-

It is possible to achieve continual improvement through small, incremental changes. CQI is itself evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

-

CQI is most effective when it becomes a natural part of the way everyday work is done.

-

It can be of limited value in situations where radical changes are required.

Attempts at CQI in practice can be frustrating. Some useful tips to bear in mind are:

-

Define the problem before trying to solve it.

-

Before you try to control a process, understand it.

-

Before trying to control everything, first find out what is important and prioritise your efforts.

-

Work on the processes that will have the biggest impact.

-

Look at failure as a learning opportunity.

CQI is covered more fully in Chapter 5.

Quality assessment seeks to compare performance against explicit a priori criteria. It may be accomplished by observation, analysis, interview, a review of processes, evaluation of deliverables, measures, and identification of issues. It helps to highlight gaps in performance and identifies opportunities for improvement. It applies equally to clinical and non-clinical aspects of care within the practice and should lead to putting quality improvement initiatives in place.

Quality control is an operational technique that focuses on the/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses