Chapter 2

Nightguard Vital Bleaching

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to consider the indications for nightguard vital bleaching and to outline the technique. Tray design and issues pertaining to existing restorations are covered.

Outcome

On reading this chapter the practitioner will be familiar with the pre-bleaching assessment of patients, the protocol for nightguard vital bleaching, and tray design.

Introduction

Nightguard vital bleaching has revolutionised aesthetic dentistry in that it produces a safe, effective and scientifically proven method of improving the appearance of discoloured teeth.

Development

The most popular, predictable and well-researched method of bleaching teeth is nightguard vital bleaching. This technique was developed by Haywood and Heymann in 1989. With this method, 10% carbamide peroxide is placed in a customised tray which is worn by the patient while asleep, hence the expression nightguard vital bleaching.

Haywood and Heymann were largely responsible for the clinical development and the scientific evaluation of nightguard vital bleaching. They based the development on earlier work by Klusmier, Wagner, Austin and Munro. Klusmier was an orthodontist, Wagner a paedodontist, Austin a general dentist and Munro a periodontist. Working independently, these individuals noted lightening of teeth as a side-effect of using carbamide peroxide in the management of gingival tissue conditions. It was Haywood, however, who made bleaching more widely available, following rigorous scientific evaluation.

The most acceptable evidence for good clinical practice is based on the results of prospective, randomised, double-blind, controlled clinical trials. Such trials are relatively rare in dentistry but a number of such trials have confirmed the safety and efficacy of nightguard vital bleaching. Colour changes have been reported to be maintained over periods of up to four years. Figs 2-1 and 2-2 show examples of teeth before and after bleaching.

Fig 2-1 Discoloured teeth before bleaching.

Fig 2-2 Teeth after bleaching.

Patient Management

All dental procedures have advantages and disadvantages. Assessment of patient expectations of bleaching is extremely important and should be done at the earliest opportunity. With nightguard vital bleaching the main clinical issue is compliance in wearing the tray with the bleaching gel in it for the required periods of time.

If patients indicate an interest in bleaching, it is good practice to have information packs available. These packs can be e-mailed or posted to patients prior to their consultation in order to give them basic information on bleaching and time to reflect on the advantages and disadvantages ahead of the consultation appointment.

There is no reason to avoid the use of occlusal coverage trays in patients with a history of temperomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD). It is prudent, however, to warn patients with a history of TMD that they may experience some mild discomfort. There are no reports of patients undergoing nightguard vital bleaching complaining of TMD during the bleaching process. In fact, some TMD patients may experience some relief of their symptoms, given that the soft bleaching tray may double as a soft TMD guard.

Pre-examination Questionnaire

A patient pre-examination questionnaire may be a useful adjunct prior to the consultation. This should include questions such as:

-

What do you wish to achieve?

-

Have you tried any other treatment for your teeth? If so, how did you find the results?

-

What do you think has caused the problem?

-

What would you consider a satisfactory solution?

(Please note, if somebody answers “very white” be careful, as their expectations may be too high. “Somewhat lighter teeth” is a much more realistic treatment objective.)

-

How long do you think treatment may take to achieve the desired result?

Protocol

The protocol for nightguard vital bleaching is based on that developed by Haywood and Heymann and is as follows:

-

A history is taken, a detailed clinical examination carried out and a differential diagnosis is made in respect of the cause of the discolouration.

-

Restorations in the target and adjacent teeth are recorded. Veneers or crowns are charted as these, together with other existing restorations, will not change colour with bleaching.

-

A note is made as to whether the periodontal tissues are thick or thin (Fig 2-3).

-

A three-in-one syringe is used to blow air around the teeth to be bleached and any sensitivity recorded. Patients should be warned that if any teeth are sensitive at the time of initial examination then these teeth are likely to get much more sensitive with bleaching (Fig 2-4). Patients presenting with sensitivity may need to bleach for two hours only at a time, rather than for the typical overnight period.

-

Tooth surface loss caused by, in particular, erosion is noted as the affected teeth may be sensitive and become more sensitive with bleaching (Fig 2-5). Tooth wear due to attrition is rarely a problem when bleaching.

-

The shade of the teeth is agreed with the patient by reference to a value-oriented (from light to dark) shade guide. This shade is recorded in the notes and a written record given to the patient.

-

The patient’s expectations, whether they are realistic or not, need to be assessed. If a patient whose teeth are already very white insists that they are too dark, it is probably unwise to proceed with bleaching. A diagnosis of possible dysmorphophobia (distortion of body image) should be considered.

-

The option of bleaching just one arch rather than both arches should be discussed with the patient.

-

Any abnormalities of enamel and dentine, the extent and sufficiency of any restorations and the presence or absence of any periodontal conditions are noted (see Fig 2-6).

-

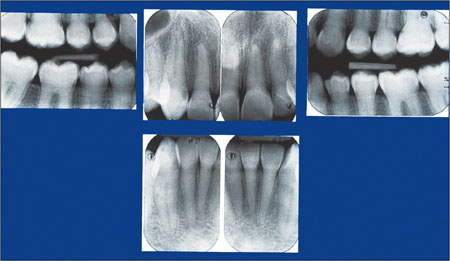

Radiographs, if appropriate and indicated, are taken and a note made of any relevant findings, including periapical status, sclerosis, atypical pulp morphology or size (see Fig 2-7).

-

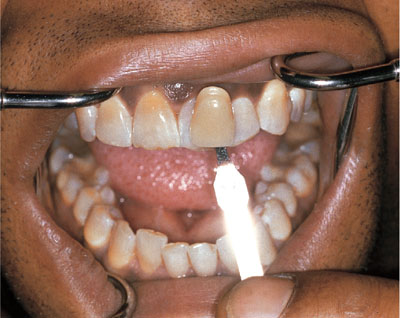

A check on whether the patient retches can be made by running a finger along the expected extension of the bleaching tray. If patients retch, or are unable to tolerate having an appliance in their mouth for prolonged periods while awake or asleep, then nightguard vital bleaching is unlikely to be successful. Frequently, patients who retch have a history of having had an invasive procedure such as tonsillectomy or extraction of teeth under general anaesthesia. Patients who have experienced a difficult general anaesthetic frequently show great reluctance to have an appliance in their mouth. It is prudent to discuss such details as part of the patient’s history, prior to incurring the costs of making bleaching trays. Retching when an impression is being taken may be a warning of future difficulties with compliance. • A photograph is taken of the teeth to be bleached and the opposing teeth, with a shade guide tab being held adjacent to the teeth as a reference (Fig 2-8).

-

The alternatives to bleaching are discussed. Attention is drawn to the fact that restorations will not change colour. This is a very important aspect of consent for bleaching. If this is not done before bleaching is started patients may think that their restorations are getting darker or otherwise damaged as their natural teeth are becoming lighter.

-

Patients may blame the dentist for changing the colour of their restorations and expect these to be replaced free of charge. The clinical and laboratory costs of replacing restorations can easily exceed the cost of bleaching. The apportionment of the costs of such treatment can be the subject of dispute.

-

If veneers, crowns, bridges or implant-retained crowns are lighter, the patient should be advised that bleaching can lighten the natural teeth to match the restorations (Figs 2-9 and 2-10).

Fig 2-3 Thin periodontal tissues. Note the dehiscence at the lower right central incisor.

Fig 2-4 Recession at the upper left lateral incisor and canine. These teeth are likely to be sensitive when bleaching.

Fig 2-5 Erosion of the palatal aspects of the upper incisors. These teeth are likely to be sensitive when bleaching.

Fig 2-6 A case of dentinogenesis imperfecta.

Fig 2-7 Radiographs reveal the absence of pulp chambers and canals.

Fig 2-8 The shade tab is held beside the teeth when the preoperative photograph is taken. This acts as a reference to monitor changes during bleaching.

Fig 2-9 Dark teeth before bleaching with lighter crowns present on the upper central incisors.

Fig 2-10 The natural teeth have been bleached to match the crowns. The crowns have not changed colour.

If the natural teeth are lighter than adjacent crowns/veneers then bleaching will make things look worse. Patients with existing restorations need to be warned to control the rate of bleaching and not to overbleach the natural teeth. It is prudent to limit the amount of bleaching gel given to such patients and to review them at one-week intervals.

Patients need to be told that if the natural teeth start to go lighter than the restorations, they must stop bleaching immediately and return to the surgery for reassessment (Figs 2-11 and 2-12).

Fig 2-11 Existing crown on the upper right central incisor with discoloured adjacent and opposing teeth.

Fig 2-12 Teeth adjacent to and opposing the crowned upper right central incisor have been bleached. The colour of the crown has not changed. />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses