Chapter 2

Immunological Problems of the Oral Mucosa

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to review immunological oral disease, including lichen planus, oro-facial allergic disorders, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, mucocutaneous autoimmune disorders, vasculitis and systemic autoimmune disorders presenting in the head and neck region.

Outcome

After reading this chapter you should be able to understand the features of immunological disease affecting the head and neck, together with the systemic effects of these diseases and factors influencing their presentation or management.

Introduction

Immunological oral disease is a very broad subject. Many mucosal and periodontal problems are caused either directly or indirectly by the host’s immune system. Some oral manifestations represent mouth changes as part of a whole body process, and other conditions produce lesions or symptoms mainly or only in the mouth. In this chapter immunological problems, including the oral effects of allergy, will be reviewed together with the oral mucosal effects of immunological reactions to the oral mucosa.

Orofacial Allergic Disorders

Allergy is usually classified by its four main methods of presentation:

-

type 1 – immediate (anaphylactic)

-

type 2 – autoimmunity

-

type 3 – immune complex disease

-

type 4 – delayed hypersensitivity.

Many patients presenting with allergy-related disease will have a history of atopy, such as eczema or asthma. The presentation of allergy in the oral soft tissues may be very varied. Gingival hyperplasia may be found in patients with allergic nasopharyngeal reaction, resulting in tissue desiccation secondary to mouth-breathing. Gingival erythema may be the result of a toothpaste allergy, often leading to a significant plasma cell infiltrate and the clinical appearance of a desquamative gingivitis. Allergy can be the basis of many other oral mucosal diseases not primarily considered ‘allergic’ disorders. These include recurrent aphthous ulceration and lichen planus. There is also an association with geographic tongue, but there is no good evidence suggesting a causal relationship.

Type 1 Reactions

These are produced by the rapid movement of fluid into the tissues from the circulation and are characterised by rapidly increasing swelling of the tissues and, following removal of the stimulus, gradual resolution over a period of hours. In this condition the transudation of fluid into the tissues from the capillaries is more rapid than the capacity of the lymphatics to drain the fluid away. This can be seen in patients with angio-oedema of the lips or tongue such as may be triggered by ACE-inhibiting drugs or C1 esterase dysfunction.

Angio-oedema

In this condition the patient will report rapid lip swelling over less than an hour with gradual resolution over the remainder of the day. Most patients with these symptoms do not seem to have a recognisable trigger, and empirical management with a long-acting, non-sedating antihistamine is the mainstay of treatment.

The combination of angio-oedema with bronchospasm, vasodilatation and rapid hypotension suggests another type 1 reaction – anaphylaxis. This reaction may follow dental treatment, such as a reaction to latex containing gloves worn by the dental team, or more rarely a local anaesthetic injection. Environmental triggers, such as a bee or wasp sting, are also possibilities, and an anaphylactic reaction should never be discounted only because no drug has been administered to the patient.

Type 2 Reactions

There are no oral conditions commonly associated with a type 2 reaction.

Type 3 Reactions

In the oral tissues the type 3 reaction is uncommon. This involves an antibody combining with an antigen in the circulation and the resulting immune complex becoming deposited in the blood vessel walls. This activates the complement cascade locally, causing perivascular inflammation of the tissues. In the mouth the most frequent clinical picture seen is the widespread inflammation and ulceration associated with erythema multiforme.

Erythema Multiforme (Fig 2-1 and Fig 2-2)

Patients with this condition present to many different medical specialties, depending on the most involved tissue. Dermatologists see those patients presenting only with skin lesions, ENT surgeons manage patients with nasopharyngeal involvement and urologists deal with lesions limited to the genitals. When all of the above sites are involved the condition is termed ‘Stevens-Johnson syndrome’. In the mouth the patient classically presents with a haemorrhagic pseudomembrane on the lips, together with oral ulceration not dissimilar to that seen in a primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Erythema multiforme is usually self limiting within 10-14 days. Patients are best managed with supportive treatment, including fluids and analgesia. There is now good evidence that many of the patients with oral symptoms have the episode triggered by herpes simplex virus, and patients with recurrent episodes of erythema multiforme in the mouth often benefit from low-dose, prophylactic aciclovir for six months. Mycoplasma pneumonia is a less commonly seen trigger, and drug reactions are unusual. Occasionally symptoms are severe enough to warrant a reducing course of a systemic steroid – for instance, prednisolone combined with an antiviral drug such as aciclovir or famciclovir. In other patients the erythema multiforme may result from an environmental trigger, and formal allergy testing can be considered for patients not helped by aciclovir prophylaxis.

Fig 2-1 ‘Target’ lesions on the arms of a patient with erythema multiforme.

Fig 2-2 Erythema multiforme presenting with ulceration and crusting of lips.

Type 4 Reactions

These are sometimes known as contact allergy or delayed hypersensitivity and present on the skin with itch, erythema and vesiculation. Whereas the latter two are found in oral reactions, itch is uncommon except when the lips or perioral skin are affected. There are many possible triggers for type 4 reactions, and in dentistry these include:

-

metals

-

dental materials

-

latex

-

food allergies.

Metal Allergies (Fig 2-3)

Nickel and palladium are the metals most commonly implicated in oral allergic reactions. Palladium is present in bonding alloys used in restorative procedures. Nickel is a constituent of most metal alloys and is thus found in stainless steel dental instruments, orthodontic appliances and cobalt chromium dentures. Contact sensitivity to nickel is reported in up to 15% of the population. After visiting the dentist the nickel sensitive patient may experience perioral discomfort, angular cheilitis and lip erythema, which may be mistaken for a recurrent herpetic lesion. The use of latex-free rubber dam on a plastic frame can reduce contact between the dental instruments and the perioral tissues, consequently reducing post-treatment symptoms.

Fig 2-3 Patch-testing: this shows a positive result (round patch of erythema) as a result of mercury sensitivity from amalgam.

Dental Materials

Many dental materials contain organic and synthetic elements implicated in sensitivity reactions elsewhere in the body. Inside the mouth reactions are unusual, although hypersensitivity to eugenol, acrylic monomer and composite resins, such as 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, have all been reported. Chemicals used in dental procedures, such as formaldehyde and sodium hypochlorite, have also been shown to sensitise some staff and patients.

Lichenoid reactions to amalgam and, less commonly, to composite restorative resins are discussed more fully later in the section on white lesions (Chapter 5). Typically the reaction to the material will resolve on its removal, but this can be a slow process taking up to six months for complete resolution.

Latex (Fig 2-4)

Many of the perioral features seen in type 4 reactions to latex gloves are identical to those described above for nickel-sensitive patients. Barrier methods, such as the non-latex dam, are useful here as well, but for the latex-sensitive patient the dental team involved in delivering clinical care should use latex-free gloves, such as the nitrile variety. Vinyl gloves are not now recommended, as they are not guaranteed to be impervious to body fluids and thus do not offer a satisfactory level of staff protection. Patients who are latex-sensitive must also be protected from other latex-containing materials in dentistry. These include local anaesthetics where latex is used in the cartridge seals, prophylaxis cups and orthodontic elastics. The use of gutta percha remains controversial in this patient group.

Fig 2-4 Perioral dermatitis in patient with a latex sensitivity after being treated by a dentist wearing rubber gloves.

Food Allergies

Food allergies have been blamed for many medical problems. A small proportion of patients have a true sensitivity to food constituents or additives, but many more claim this problem. For a true allergy to exist, not only must the suspected reaction resolve on withdrawal of the putative agent, but it must also recur on re-exposure. Coeliac disease is a true food allergy to the alpha gliaden component of wheat. There are a few oral diseases associated with allergies to food components. The most notable of these is orofacial granulomatosis (OFG) where, in some study populations, a significant proportion of patients show immediate or delayed reactions on testing to common food preservatives and flavourings. Preservatives such as benzoic acid (benzoates) and sorbic acid (sorbates) are common culprits, together with other additives in the E210-219 series. Flavouring agents, such as cinnamon and chocolate, and a variety of other everyday environmental items, such as balsam of Peru and colophony, can be identified as environmental triggers in OFG patients. Dietary and environmental agent exclusion are often the best management path for patients with this problem, but this can be difficult in view of the ubiquitous nature of the allergens in contemporary living. Food allergies are also worth considering in some patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis and angiooedema, particularly in those who respond poorly to conventional treatment.

Fixed Drug Eruptions

These are not commonly found in the oral environment, but more recently the potassium channel blocker nicorandil has been associated with tongue ulceration. The ulcer is usually shallow, about 1cm in diameter, on the lateral margin of the tongue, exceedingly painful and poorly responsive to conventional therapies. As most patients have been taking the drug for some time before symptoms develop many physicians fail to associate the ulceration with the drug. Stopping the nicorandil produces a rapid improvement in symptoms and rapid healing of the ulcer. Re-introduction of the drug is quickly followed by the return of the ulcer on the same site. If a drug reaction for an oral lesion is suspected, the dental practitioner must always discuss the problem with the patient’s physician to ensure that a suitable alternative therapy is arranged for the continuing medical problem, usually angina.

Orofacial Granulomatosis (Figs 2-5 to 2-7)

Orofacial granulomatosis is a chronic granulomatous condition limited to the face and mouth. It presents with a prolonged oedematous swelling of the lips and perioral soft tissues. Most often there is an associated angular cheilitis, with exfoliative lip dermatitis, fissuring and perioral erythema seen in a few cases. Typical intra-oral findings include mucosal oedema leading to a ‘cobblestone’ pattern together with mucosal tags and aphthous-type oral ulceration. In a minority a marked gingival erythema is noted. Rarely fistulae can develop from the mouth into the pharynx or, more distressingly, the facial skin.

Fig 2-5 Tissue tags on the buccal sulcus in a young patient with orofacial granulomatosis (OFG)

Fig 2-6 Chronic swelling of lower lip with associated bilateral angular cheilitis. These appearances are suggestive of orofacial granulomatosis (OFG) or oral Crohn’s disease. This feature is also known as cheilitis granulomatosa.

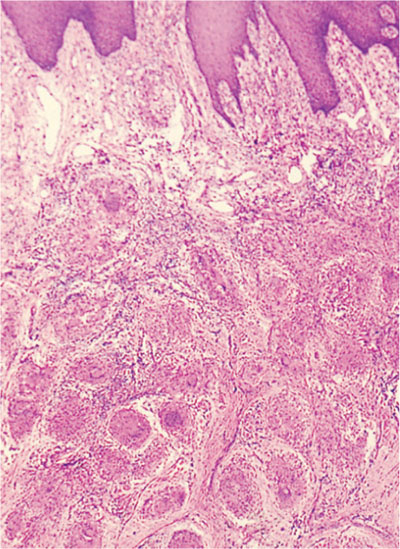

Fig 2-7 H&E stained section through the tongue demonstrating granulomatous inflammation from a patient with orofacial granulomatosis (OFG). A similar appearance would be seen in Crohn’s disease, and this specimen demonstrates how the granulomata lie fairly deep within the tissue and, as a consequence, the need for a large biopsy to allow diagnosis.

The oral lesions are due to giant cell granulomas located within the lymphatic channels draining the affected tissue. These act as a ‘plug’, preventing normal transudated tissue fluid passing back to the circulation through the lymphatics. There does not seem to be an increase in fluid entering the tissues, and the swelling seen is due to its gradual accumulation over time.

Consequently any effective treatment must prevent granuloma formation and thus allow the gradual reopening of the lymphatics. For this reason changes in appearance following any intervention can take many weeks to produce a clinical improvement. The condition can appear at any age, but most patients are in the first three decades of life. Biopsy does not always demonstrate the classical giant cell granulomas unless it is performed deep into the most affected tissue area, often as far as the muscle layer. However, distended lymphatics are usually seen. Similar pathological findings can be present in sarcoidoisis, and this condition must always be included in the differential diagnosis of chronic facial swelling. Much confusion exists within dentistry in differentiating OFG from Crohn’s disease. The label ‘oral Crohn’s’ is given when oral lesions are found in association with similar findings on biopsy, endoscopic or radiological changes noted in the ‘hidden’ gastrointestinal tract. Crohn’s disease, like OFG, is not a condition with a single cause and is likely to represent a group of conditions producing similar clinical findings. As with OFG, suggested causes for Crohn’s disease include food allergies, an infectious agent (possibly an atypical mycobacterium) or an idiosyncratic reaction to measles vaccine. Investigations for OFG patients should include a dietary history, especially carbonated beverage intake, note of any gastrointestinal symptoms of altered bowel habit or rectal bleeding, unusual breathlessness and skin lesions. Laboratory investigations vary widely between clinicians, but the serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is an important marker for sarcoidosis in many patients and is essential for every OFG patient. It is also important to check ferritin, red-cell folate and vitamin B12 levels, as low levels of these may suggest occult gastrointestinal tract disease. Additionally, low ferritin levels will exacerbate any angular cheilitis or oral ulceration present and iron must be replaced as part of the patient’s overall management. An important investigation is allergy testing to identify a suitable exclusion regimen where possible. In many patients the trigger is never found, and treatment is limited to reducing the cosmetic and psychological problems caused by the lip swelling. The use of repeated intralesional injections of a potent steroid such as triamcinolone can gradually produce an improvement in the patient’s appearance, although the benefit is usually lost over a few months. The condition seems to fade with time in many patients. However, if the swelling has been present for many years the chronic inflammatory changes will result in fibrin and possibly collagen deposition in the tissues. This makes the disfigurement permanent. In these cases the best cosmetic outcome is achieved through surgical filleting of the lip tissue.

Summary

-

Allergy is probably under-recognised as a cause of oral disease and symptoms.

-

Patch-testing is of limited value in identifying triggers for allergic problems.

-

Dietary and environmental exclusion trials are often the most useful way to identify certain disease triggers.

Lichen Planus (Figs 2-8 to 2-12)

This is a relatively common mucocutaneous condition affecting between 2–4% of the population. It can present as a purely skin problem, mucosal problem or a combination of both. Many patients present complaining of recurrent oral ulceration, and lichen planus should, therefore, be included in the differential diagnosis for this symptom. The skin lesions usually comprise an itchy, violaceous, macular-papular rash most frequently affecting the flexor surfaces of wrists, shins and midriff regions. However, other sites may be affected – such as the nails, which become dystrophic, or the scalp, leading to hair loss (alopecia). In approximately half of the patients presenting with dermatological manifestations of lichen planus the oral mucosa will also be affected. Only 10–30% of those presenting with oral lichen planus develop cutaneous manifestations, however, and this may reflect a different trigger for the two presentations.

Fig 2-8 Reticular oral lichen planus.

Fig 2-9 Lichenoid reaction on buccal mucosa due to amalgam sensitivity. Note the close proximity of the large amalgam restoration adjact to this lesion.

Fig 2-10 Major erosive oral lichen planus.

Fig 2-11 Desquamative gingivitis in a patient with oral lichen planus. A similar appearance may also be seen in patients with mucous membrane pemphigoid and can also occur as a result of a local hypersensitivity reaction. B/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses