Chapter 2

Hygiene Phase Therapy

Aims

To provide a comprehensive overview of the methods that are available for the mechanical and chemical control of dental plaque.

Outcome

After reading this chapter the practitioner should:

-

be aware of the range of toothbrush designs and interdental cleaning aids that are available

-

understand the indications for using chemical plaque control

-

have knowledge of the range of generic mouth rinses that are available for chemical plaque control.

Plaque Control Programmes

Homecare, plaque control programmes and hygiene phase therapy are crucial components of non-surgical periodontal therapy. Programmes should be based on individual patient needs in order to achieve a level of plaque control that is compatible with a stable periodontium. It is, however, unrealistic to expect patients to achieve a plaque-free dentition. Indeed, many clinical studies have confirmed that most patients, even with intensive hygiene phase therapy and regular re-enforcement of plaque control measures, will still have about 10–15% of tooth surfaces with residual plaque deposits. For the vast majority of patients with chronic periodontitis, this standard of tooth cleaning may be found to be acceptable.

Clinical trials in the 1980s confirmed that plaque control may be taught effectively in two 15 minute appointments (Table 2-1). It is important that sufficient time is dedicated specifically to the hygiene phase of therapy so that patients appreciate fully that they have the key role to play in the management of their periodontal disease. This role often necessitates significant behavioural and attitude changes with respect to oral healthcare practices. In order to achieve this, patients must be made aware that they are different from the general population with respect to their susceptibility to periodontitis and, consequently, they must achieve exceptionally high standards of homecare if treatment is to succeed.

| First visit (15 minutes) | Second visit (15 minutes) |

| Provide dental health information including, for smokers, the effects of nicotine on oral health | Ask smokers if they are ready to quit and where appropriate provide smoking cessation advice |

| Disclose and score plaque | Disclose and score plaque and compare to previous score |

| Advice on the selection of a toothbrush and give instructions in tooth-brushing | Identify any problems with tooth brushing and the use of interdental aids. If necessary, reinforce or change advice |

| Instructions on interdental cleaning | Professional prophylaxis to remove residual stained plaque |

| Professional prophylaxis to remove residual stained plaque | Always be positive and praise the patient’s efforts |

Mechanical plaque control

Plaque control refers to the removal of plaque from tooth surfaces and gingival tissues, and prevention of new microbial growth. Effective plaque control results in resolution of gingival inflammation and is fundamentally important in all periodontal therapy. Periodontal treatment performed in the absence of plaque control is certain to fail, resulting in disease progression or recurrence. Mechanical plaque control is performed using toothbrushes, toothpaste and other cleaning aids. Plaque control programmes should be tailored to the requirements of individual patients, addressing their local risk factors at the whole mouth, tooth and site levels (see book 1 in this series, Understanding Periodontal Diseases: Assessment and Diagnostic Procedure in Practice).

Manual Toothbrushes

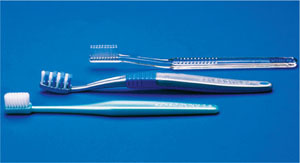

Conventional, manual toothbrushes vary in design and size, and the type of brush used is a matter of personal preference (Fig 2-1). Bristles are generally made of nylon, which is relatively flexible, resistant to fracture and does not become saturated with water. Bristles are arranged in tufts, and round-ended bristles cause fewer scratches on the gingiva than flat-ended bristles do. Softer bristles have greater flexibility, and have been shown to reach further interproximally and subgingivally. Hard bristles are more likely to result in gingival trauma. However, the technique and the force applied when brushing are more important determinants of plaque removal capability and gingival trauma than the hardness of the bristles themselves. With use, toothbrushes show signs of wear and flattening of bristles, and should be replaced approximately every three months. A typical, conventional, manual toothbrush is likely to conform to the following standards:

-

brush head dimensions – 1.5–2.5cm long and 0.15–0.75cm wide

-

four rows of “bristles” of medium texture and made from nylon polymer filaments of 10–12mm length.

Fig 2-1 A small number of the wide range of manual toothbrushes that are available on the market.

Specialist toothbrushes are available for certain patients and specific clinical indications (Fig 2-2):

-

children’s toothbrushes – which have a reduced head size and a more bulky, easier-to-grip handle

-

single tufted toothbrushes (interspace brushes) – which can be used in areas that are inaccessible to a conventional brush, e.g. sites of gingival recession, furcations and large interdental spaces

-

orthodontic toothbrushes – which have a V-shaped indentation along the head of bristles to accommodate the components of fixed orthodontic appliances

-

denture brushes – which may be used with partial or complete dentures. They usually have a dual-purpose head with tapered bristles that are much firmer than those of a conventional toothbrush.

Fig 2-2 Specialist toothbrushes: (left to right) a child’s toothbrush, a single tufted toothbrush and an orthodontic toothbrush used to clean around the components of fixed orthodontic appliances.

Powered Toothbrushes

The brush heads of powered toothbrushes (Fig 2-3) tend to be more compact than those of their manual counterparts – a feature that facilitates interproximal brushing and cleaning of, in particular, posterior teeth. Bundles of bristles are arranged in rows in a rectangular head or in a circular pattern mounted in a round head. Some brushes have single, compact tufts, which are specifically designed for interproximal cleaning. The traditional design of brush head operates with a side-to-side or back and forth motion. Circular heads have an oscillating motion.

Fig 2-3 Three powered toothbrushes with different handle and brush head designs. The brushes with circular arrangements of bristles operate with an oscillating motion whereas the traditional design of brush head operates with a side-to side or back and forth motion.

Powered brushes have previously been considered particularly beneficial for special needs patients, patients with fixed orthodontic appliances, and those who are hospitalised or institutionalised and who may need a third-party/carer to assist with toothbrushing. It is now more generally accepted that powered brushes may be advantageous for a much wider group of patients who might otherwise be unable to achieve an “acceptable” standard of plaque control. Numerous studies have confirmed that, for most patients, powered brushes are more effective than manual toothbrushes. This may be because of better mechanical cleaning, although the novelty of using a powered toothbrush may also improve compliance, especially in children.

Contemporary designs of powered toothbrushes have a number of special features that enhance their use:

-

timing mechanisms

-

easy start features which increase the brushing force over the first few occasions of use

-

dual-speed options

-

programmable pacers that provide feedback to signal the amount of time that has been spent in one part (quadrant) of the mouth.

Toothpastes

Toothpastes are used as aids for cleaning tooth surfaces and contain abrasives (e.g. silica), water, preservatives, flavouring, colouring, detergents and therapeutic agents (e.g. fluoride). Abrasives (approximately 20–40% of the content) enhance plaque removal, but may result in damage to the tooth surface if there is overzealous brushing. Smokers’ toothpastes and tooth powders contain significantly higher proportions of abrasives and their use is not recommended. Chemotherapeutic agents (e.g. chlorhexidine) may be added to toothpastes. These agents are discussed in more detail later in this section.

Toothbrushing techniques

The majority of patients use a “horizontal scrub” technique, which does not clean effectively around gingival margins and can lead to tooth wear. When brushing, a systematic approach is essential, and all accessible surfaces of all teeth should be cleaned thoroughly. The Bass technique is useful for the majority of patients with or without periodontal disease (Fig 2-4). The Charters’ method is useful for gentle gingival cleaning, particularly during healing immediately after periodontal surgery and for patients with necrotising gingivitis in whom the painful symptoms have resolved.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses