CHAPTER 2

Edentulism, Digestion, and Nutrition

This chapter reviews current evidence of the consequences of tooth loss on dietary patterns and the effect of conventional prosthetic rehabilitation. It also details the effect of implant-supported prostheses on patients’ perceived ability to chew as well as changes in patients’ posttreatment food selection patterns. The potential effect of these changes on nutritional status is illustrated with pilot data from a study of mandibular overdentures supported by two implants.

Nutrient Intake and Dentition

Changes in the ability to eat food also are apparent in nutrition intake. Edentulous individuals living independently have been shown to have a lower nutrient intake compared with dentate adults.12 Those with 21 or more teeth consumed more of most nutrients, especially the nonstarch polysaccharides (dietary fiber), while edentulous adults consumed less nonstarch polysaccharides, protein, calcium, nonheme iron, niacin, and vitamin C. It also was found that mean daily intake of nutrients and total caloric intake correspondingly increased with the number of teeth.13 In older patients, a greater number of occluding pairs of teeth was associated with higher consumption of intrinsic and milk sugars in addition to more nonstarch polysaccharides compared with dentate adults.6,12 Nonstarch polysaccharide levels also have been shown to be lower in edentate adults than in dentate adults9-14; these same levels are reduced in patients who have difficulty chewing.15 This is reflected in the Survey Europe on Nutrition in the Elderly: Concerted Action study, which investigated the dentition and dietary intake of the elderly in 12 European cities and the state of Connecticut in the United States. Edentulous patients were found to have more chewing difficulties; lower intakes of carbohydrates and vitamin B6; and a trend toward reduced vitamins B1 and C, fiber, calcium, and iron intake compared with dentate adults.16

Blood-derived values of key nutrients also appear to be influenced by oral health status. Data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) conducted in elderly men and women from Great Britain showed that, even after controlling for confounding variables, plasma ascorbate and retinol were significantly associated with dental status. Furthermore, the relationship between ascorbate and tooth number was statistically significant. There also was a trend toward higher levels of most nutrients in dentate individuals. These findings are consistent with the results of the dietary intake of these populations.13

The effect of these findings perhaps is more clearly seen in the frail elderly. In a study reviewing the relationship between the oral and systemic health of institutionalized subjects, those with compromised oral function had both a significantly lower body mass index (BMI) and low serum albumin concentration.17 The presence of less than six occluding pairs of teeth was a strong predictor of malnutrition as determined by these parameters. A 6-year longitudinal study of the institutionalized elderly showed a greater decline in physical ability and higher mortality rates in edentulous subjects without dentures compared to patients with 20 or more teeth.18

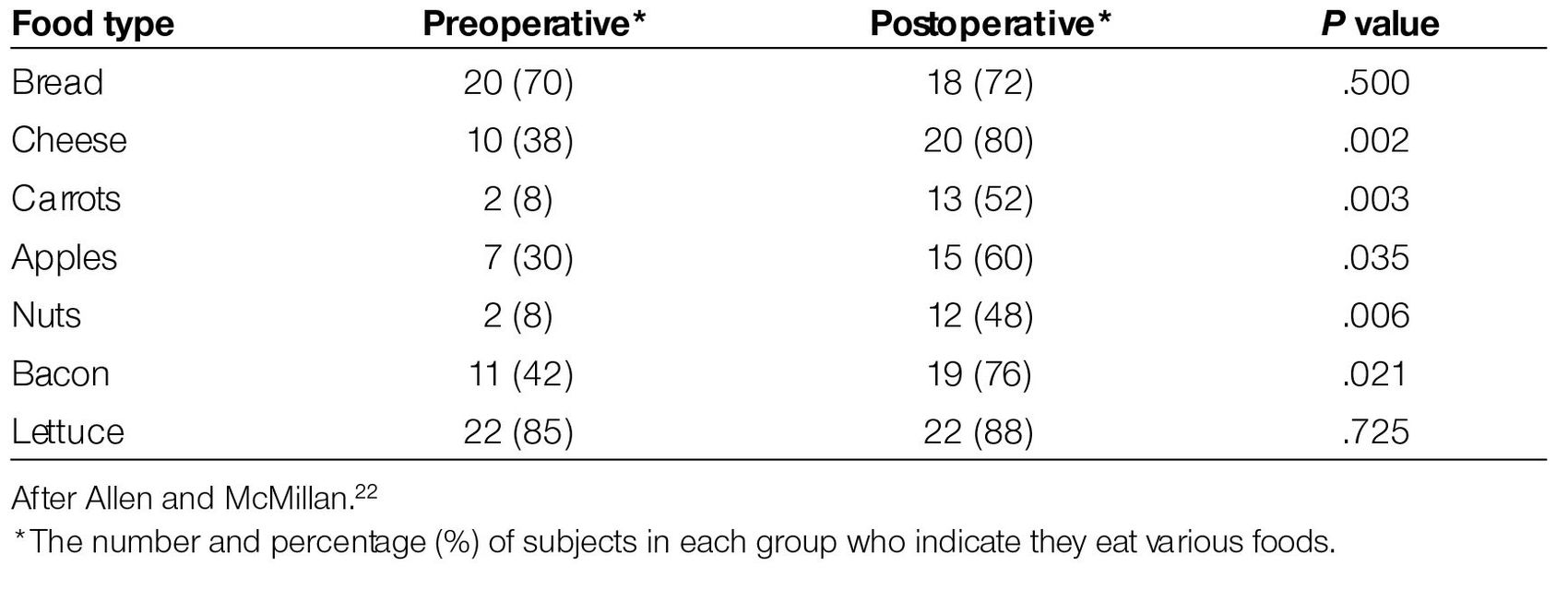

Table 2-1 Change in food selection in patients treated with fixed or removable implant-supported prostheses

Partially dentate patients with less than 10 occluding pairs of teeth have been shown to have undesirable nutrient intake both before and after rehabilitation. Patients with either a fixed or removable mandibular prosthesis w/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses