Chapter 2

Communicable diseases in the dental surgery

HOW INFECTIONS ARE SPREAD

Microorganisms must attach to or penetrate the surfaces of the body in order to establish themselves, and they have the potential to cause infection and disease in the host. This association between microbes and human cells is very specific and has evolved over millions of years; thus, many species of bacteria which colonise the mouth and oral tissues are not found anywhere else in the human body or at any other site in the biosphere.

While the body is well protected by intact skin, the orifices of the body are sites of potential entry for infection and are protected by secretions such as saliva and tears and defence mechanisms such as tonsils and lymph nodes. However, they remain a potential weak link in our defences, and hence we wear protective clothing such as masks to protect the respiratory tree, lips and mouth from infection and goggles to protect the eyes as part of infection control and prevention protocols.

The vast majority of microbes do not cause infection in humans; indeed a resident or commensal flora on the skin or in the gut and mouth is essential for health. These bacteria live in harmony with our body and protect us by preventing other more harmful bacteria attaching to and colonising the body. An example of this is seen in dental plaque where the species such as Streptococcus sanguis is associated with health and Streptococcus mutans with rampant caries in patients on high-sucrose diets.

Some microbes which are considered commensal and harmless can cause infection and disease when the host’s immune system is compromised by, for example, age, diseases such as diabetes or cystic fibrosis, or infection such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). These are called opportunist pathogens and for this reason dentist must take particular care in taking a medical history of patients to enquire about conditions which may make patients more susceptible to infection and take steps to protect these vulnerable patients.

A successful microorganism which can cause disease (pathogen) must have a means of transmission from host to host; otherwise it would eventually disappear. Some microbes such as avian influenza virus, rabies virus, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) and Salmonella use animals as their main host and occasionally spread to humans. These are known as zoonosis and although are important in the food industry and agriculture, they do not usually pose a risk of infection in the dental clinic. Insects such as mosquitoes can act as a means of transmission of infection of malaria, and these infections may impact on dentistry as they are usually blood-borne infections and could be potentially transmitted during operative dentistry. The dental clinic offers the potential to transmit infection from person to person and the method of prevention of this transmission is the essence of cross-infection control.

RESERVOIRS AND SOURCES OF INFECTION

For infection to spread there must also be a source of infection, which is most often a patient attending for dental treatment, and these sources may present three stages of infection/colonisation:

- Patients suffering from an infectious disease known as the index case, e.g. influenza, measles, AIDS and tuberculosis (TB)

- Patients in the prodromal or convalescent stage of infection, e.g. herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV)

- Healthy carriers of disease, e.g. Streptococcus pyogenes (sore throat), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Neisseria meningitidis (meningitis) and Haemophilus influenzae (bronchitis)

Patients with acute infection are usually very infectious and release large numbers of microbes into the environment. Those with serious infections rarely attend for routine clinical dentistry, but the dentist must be able and willing to treat such people in a manner which will ensure the safety of other staff and patients and consistent with offering high standards of dental care to the patient. It is a good policy to postpone elective treatment during the infective period which improves the patient’s comfort and eliminates the risk of infection.

Much attention has been focused on convalescent and asymptomatic carriers of infection as these patients are often infective and the infections represent some of the most serious risks of transmission in the dental practice and the carriers cannot be readily identified. Those patients who carry hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) cannot be identified, but a good medical history is useful since some people will know their carrier status.

Healthcare associated infection (HCAI) or hospital-acquired infection, or nosocomial infection are infections caught or emerge while in hospital, for instance, infections caught from other patients or during treatment, and are a major cause of concern to the medical profession. Infections are considered HAI if they first appear 48 hours or more after hospital admission or within 30 days after discharge from hospital. Prevalence rates vary greatly but are of the order of 10% in many countries, with urinary tract infection and pneumonia being most prevalent. Outbreaks of MRSA, Clostridium difficile and antibiotic multi-resistant organisms have created much anxiety amongst patients and the dental team must know how to prevent the spread of these microbes should a patient present in their clinic. Because the vast majority of dental procedures are performed outside an institutional environment, HAIs are less often reported, but there is, as discussed in Chapter 1, a risk of infection in every clinical setting. Much information aimed primarily at health professionals has sought to reduce the incidence of HAI and has emphasised the importance of procedures such as hand washing and barrier to personal protection discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. (Further information on HAI can be found at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthprotection/Healthcareacquiredinfection/index.htm.)

INFECTIOUS DISEASE BY ROUTE OF TRANSMISSION IN THE DENTAL SURGERY

There are three main routes by which infection can be transmitted in a dental practice:

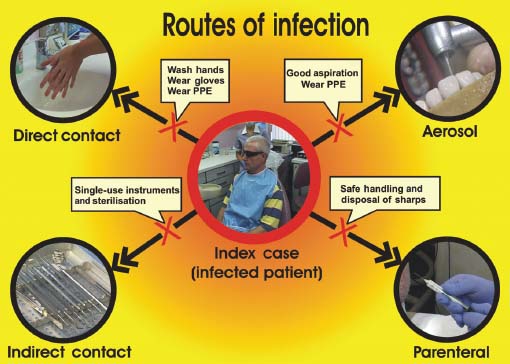

It is important to know the route of transmission of an infective agent as the infection control measures as set out in standard precautions are targeted at blocking the potential route of transmission (Figure 2.1). Problems often arise when the routes of transmission of new emerging infections pose a challenge to our standard precautions. For example, vCJD is difficult to denature and remove from instruments; hence, the contact route of transmission may not be blocked by our routine standard precautions and they have to be modified in the light of experimental evidence to reduce the risk of transmission.

Figure 2.1 Routes of transmission of infection in the dental surgery and how they are blocked by standard infection control precautions (courtesy of Paul Morris).

Direct and indirect contact spread of infection

This is the most obvious and commonly appreciated mode of spread of infection by dental professionals. Contact spread is a direct spread from person to person, or indirectly via equipment, via contaminated fluids, or from food or objects such as towels.

Pathogens which have a risk of transmission by contact include the herpes group of viruses – herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) a, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and the respiratory viruses. While we associate the spread of respiratory viruses with the spread by aerosol, it must not be forgotten that the patterns of transmission observed during nosocomial outbreaks of influenza suggest that large droplets from a patient with infection and contact (direct and indirect) are the most important and most likely routes of spread. Also, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a highly infectious respiratory virus, which causes outbreaks in hospitalised children is largely spread by direct contact. Many bacterial infections could potentially be transmitted by contact in the dental clinic but the one which causes most concern especially in oral surgery is S. aureus, in particular MRSA.

HSV is very infectious and patients commonly attend dental clinic with a herpes labialis or cold sore which can infect the dentist’s fingers, resulting in an intensely painful lesion known as a herpetic whitlow. VZV which causes chicken pox and shingles is a risk to the fetus and pregnant women, and in many countries including the UK, dentists must be vaccinated if they have no natural immunity to prevent primary infection. This is to reduce the risk of infection to pregnant women from the health care worker (HCW).

MRSA infection is of concern because they are resistant to antibiotics including methicillin and other more common antibiotics such as oxacillin, penicillin and amoxicillin. About 25–30% of the population are colonised with S. aureus but only approximately 1% carry MRSA. MRSA occurs most frequently among persons in hospitals and health care facilities, and thus the dentist may be at greatest risks of becoming colonised during locum visits to patients in such institutions. The main mode of transmission of MRSA is via the hands of the HCW which may become contaminated by contact with either colonised or infected patients or from sites on their own body which are colonised or infected.

Community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) is a different strain of MRSA that is easier to treat, and infects younger populations in the community and can, if left untreated, cause very serious disease. CA-MRSA primarily causes infection in athletes, children in day care and intravenous drug users, where there is close skin-to-skin contact and spread is encouraged by poor hygiene. (Further information on MRSA can be found at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/AdvanceSearchResult/index.htm?searchTerms=MRSA.)

Prevention of person-to-person spread of infection

The primary source of spread from person to person is by hands and clothing and this route of infection is easily interrupted by hand washing and wearing of gloves (Figure 2.1), as outlined in Chapter 5.

Prevention of spread of infection from equipment

Equipment including dental instruments must be decontaminated between patients (Figure 2.1) or be discarded safely if they are designated single use, as outlined in Chapter 7. Impression materials should be disinfected to reduce the risk of infection of dental technicians and comply with regulation concerning the transport of infected material by postal services. Dental chairs and units must also be cleaned and disinfected between patients and this is facilitated by dividing the surgery into ‘zones’ of different levels of contamination, as outlined in Chapter 8.

Prevention of spread of infection by fluids

The dental unit waterlines are a potential source of the spread of infection by both aerosol and contact (Figure 2.1), and the management and method of reducing this risk is discussed in Chapter 9. Disinfectant and detergents must be stored in concentrated form according to the manufacturer’s recommendation as they can become a source of infection by bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa which are resistant to some disinfectants and pose a risk to immunocompromised patients.

The transmission of infection via food is a major source of concern in society but should not be a risk in dentistry since no food should be taken in surgery and adequate kitchen facilities should be provided for staff.

Parenteral transmission of infection via the bloodstream

Many organisms are potentially transmissible in the occupational setting via percutaneous (sharps) (Figure 2.1) or mucocutaneous (mucous membrane/broken skin) routes. The so-called blood-borne viruses (BBVs) are of primary concern. The BBVs which present most cross-infection hazard to HCWs are those associated with a carrier state with persistent replication of the virus in the human host and persistent viraemia. These include HIV and hepatitis B and C.

Hepatitis B virus

Hepatitis B is a blood-borne and sexually transmitted virus, a member of the Hepadnaviridae DNA family, which causes inflammation of the liver. Transmission usually occurs by unprotected sexual intercourse, intravenous drug misusers, sharing contaminated needles and from mother to baby at birth. Up to 90% of babies infected perinatally and around 5–10% of those infected as adults develop chronic carrier status. Many infected people have no symptoms, but others have a flu-like illness with nausea and jaundice. The persistence of the ‘e’-antigen correlates with a high level of viral replication and increased infectivity. Hepatitis B becomes a chronic infection when the infection persists longer than 6 months and more than 350 million people worldwide have chronic infections. Hepatitis B is a significant problem for public health within the European region with over 1 million newly infected, 14 million chronically infected and 36 000 deaths annually attributed to HBV. The increase in prevalence is influenced by migration rates from high-incidence areas. Hepatitis B vacci/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses