Chapter 2

Assessment of the Edentulous Patient

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to outline the procedures for assessing edentulous patients.

Outcome

At the end of the chapter, the practitioner should understand that there are many functional and psychological consequences of edentulousness. These are difficult to rectify with complete replacement dentures, and a successful outcome depends on clinical and patient-related factors. The practitioner should realise that a treatment plan should take into account these factors, and that the plan should be tailored to the needs of the individual. This includes preliminary treatment designed to improve the health of the denture-bearing area. It should be recognised that good clinical technique is important in preserving healthy tissue and function.

Consequences of Edentulousness

The anatomical changes which occur following extraction of natural teeth can broadly be divided into intraoral and extraoral changes. These will differ between individuals who remain partially dentate and those who become edentulous. As people age, loss of alveolar bone is inevitable. However, following total tooth loss, alveolar bone resorption is greatly increased. Alveolar bone height and width decreases markedly (Figs 2-1, 2-2). Most of this change occurs in the first year following extraction, but remains an inexorable process throughout life. Resorption occurs on the buccal aspect of the maxillary ridge and the lingual aspect of the mandibular ridge. Despite extensive research, the reason for the great individual variation in bone loss remains unclear. It seems likely that a combination of local and systemic factors may be responsible for this phenomenon.

Fig 2-1 Lateral cephalogram of a 62-year-old patient with severe alveolar resorption.

Fig 2-2 Edentulous mandible with gross alveolar resorption.

Further consequences of tooth loss include:

-

impaired mastication

-

limitation of food selection, especially nutritious foods such as fruits and vegetables

-

speech impairment

-

change in appearance

-

psychosocial impact.

The influence of tooth loss on masticatory ability, masticatory performance and dietary selection has been well documented. Objective tests of masticatory performance indicate that chewing efficiency of edentulous adults is approximately 20% that of dentate individuals. Subjective tests which assess patients’ attitudes to food choice suggest that edentulous patients tend to favour highly flavoured soft foods which are of low nutritional value. Reasons for this are complex, and include socioeconomic factors as well as denture-related causes. Surveys of nutritional intake report that edentulous adults have a lower intake of fibre, vitamin C and other important nutrients compared with dentate adults. This suggests that edentulous patients with poor quality diet are at a higher risk of serious illness, including cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Loss of anterior teeth affects speech and can be a difficult problem to deal with, particularly in patients with a skeletal Class 2 jaw relationship. In addition to preserving bone, teeth support soft tissues such as the cheeks and lips. These, in turn, influence appearance, which is adversely affected once teeth are lost. This is most noticeable in the circumoral region, as the commisures of the lips collapse inwards. A further consequence is loss of vertical dimension and this has the effect of approximating the chin to the nose (Fig 2-3). Some of these changes can be rectified by complete replacement dentures, but there are some limitations. In cases of severe resorption, it may be impossible to meet the patient’s aesthetic requirements and, at the same time, provide stable replacement dentures.

Fig 2-3 Edentulous patient without dentures. Note the approximation of the chin to the nose.

Increasingly, researchers are beginning to look at wider issues of health-related quality of life. As well as effect on function, it is now recognised that tooth loss has much broader social and psychological impact. Acceptance of tooth loss and complete replacement dentures is variable and subjective. Research indicates that patients who have lost their natural teeth have poorer oral health-related quality of life than patients with their own teeth. From a clinical point of view, the outcome of complete replacement dentures in the rehabilitation of edentulousness is difficult to predict. As described above, there are a number of difficult functional problems to overcome. Still, some patients manage very well with technically inadequate dentures. It would appear that satisfaction with the outcome is not always strongly correlated with the technical quality of dentures or the denture-bearing tissues. Some studies also indicate that patients with denture-wearing difficulties score highly on neuroticism indices. Whilst complete replacement dentures continue to be successful for many patients, there are significant numbers of edentulous patients for whom these dentures will not be satisfactory. Despite this, there is ample evidence that well-constructed complete dentures help provide satisfactory oral health-related quality of life for many edentulous patients.

Planning New Complete Dentures

The aim of the first visit is to assess the patient and to formulate a treatment plan. The treatment plan should address the specific requirements of the individual patient. Care should be taken not to leap into the clinical phase of treatment without carefully listening to the patient’s complaint. There is wide variation in patient satisfaction with the outcome of complete denture therapy, and the ability of the patient to adapt to change and to the limitations of complete denture therapy should be assessed. It is at this stage that patient expectations should also be determined.

The dental practitioner will encounter a wide variety of presentations, such as: patients with very old dentures and poor quality denture-bearing areas; very old, frail patients; “maladaptive” patients; and patients unhappy with, and seeking, replacement of new dentures.

Assessment of the Patient

The patient’s concerns regarding their current dentures and their aspirations for treatment must be assessed. The patient should be asked about the following:

-

Reason for replacing dentures.

-

Is this problem longstanding or of recent onset?

-

How long have they been edentulous?

-

How many sets of complete dentures have they had in the past?

-

Medical history.

-

Social history.

Perhaps the most common problem is that of “loose” dentures. This may be the only complaint, or it may be one of a number of complaints, including:

-

pain

-

dissatisfaction with appearance

-

inability to chew food

-

speech problems

-

damaged acrylic or fracture of a denture.

Many patients are able to articulate the precise problem they have with their dentures. However, some patients find it difficult to express the nature of their problem, and the clinician should devote some time to eliciting the complaint in such cases. The clinician should enquire about the duration of the complaint. Once the nature of the complaint has been determined, the next stage is to relate this complaint to the examination findings.

Details of the patient’s medical history should be recorded. This can be done using a self-completion proforma, but should be carefully checked by the clinician when assessing the patient. Of particular relevance in treating edentulous patients are factors likely to influence adaptation to wearing dentures and factors affecting tolerance of the treatment process. These include:

-

Neuromuscular disorders, e.g. Parkinson’s disease; stroke

-

Dry mouth (xerostomia) associated with

-

medications, e.g. antihypertensives, diuretics, antidepressants

-

diabetes mellitus

-

salivary gland disease

-

post radiotherapy to the orofacial region

-

-

Psychiatric illness

-

Nutritional deficiency (may be associated with burning mouth syndrome)

-

Arthritis (affects the treatment process).

The patient’s social history should also be discussed. If they smoke and/or consume alcohol, the clinician should enquire about the amount and frequency, bearing in mind that these are aetiological factors in the development of oral cancer. If the patient lives at a considerable distance from the surgery, can they attend for the number of visits required to make dentures? If they rely on a relative or friend to bring them to the surgery, will they be able to come for each and every visit?

Examination of the Patient

Following assessment of the patient, a thorough clinical examination should be undertaken, including:

-

extraoral examination

-

intraoral examination

-

dentures in situ

-

dentures out of the mouth.

Extraoral examination

At the outset, one should assess the “biological” age of the patient in relation to the chronological age, as this is a useful prognostic indicator. The patient shown in Fig 2-4 is 91 years old and lives independently. He has been edentulous for 60 years and has learned to adapt to dentures extremely well. He has an active social life, and the prognosis for treatment is considered good. In contrast, the patient shown in Fig 2-5 is 53 years old and has poor general health. He appears much older than his chronological age, and may struggle to cope with new complete dentures.

Fig 2-4 Biological versus chronological age – 91-year-old edentulous, independently living male.

Fig 2-5 Biological versus chronological age – 53-year-old male with poor health.

In the facial region, the patient’s skeletal profile should be assessed with the dentures in situ (i.e. Class 1, 2 or 3) bearing in mind that, following loss of the occluding vertical dimension due to wear of the denture teeth, the mandible may appear prognathic (Fig 2-6). Take note of the muscle tone and assess lip support and the proximity of the chin to the nose in both facial and lateral views (Fig 2-6). If the patient has a neuromuscular disorder or has had a cerebrovascular accident (stroke), muscle tone should be carefully noted. The health of the tissues, particularly the lips and corners of the mouth, should also be assessed and any pathology diagnosed and treated.

Fig 2-6 Edentulous patient with dentures in place: (a) lateral view (b) facial view.

Intraoral examination

The following aspects are of particular interest in the intraoral examination:

-

The condition of the denture-bearing tissues. This includes the height of the residual alveolar ridge, the condition of the supporting tissues and the presence of mucosal lesions and non-pathological conditions such as bony exostoses.

-

The condition of the dentures themselves.

Ridge dimensions

The height and width of the alveolar ridge should be assessed. Shallow ridges offer little stability, and they may have resorbed to the extent that the genial tubercles and mylohyoid ridge become superficial. If the ridge is narrow, then it may not provide adequate support for a denture. The presence of bony exostoses (“tori”) should be noted. These are most commonly seen in the centre of the palate and on the lingual aspect of the anterior mandible. If they are prominent, then it may be impossible to extend the denture into the sulcus and this will affect denture retention. In this situation, prominent tori may need to be surgically removed.

Soft tissues

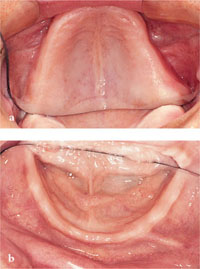

The tissues overlying the ridges should be examined visually and palpated. Ideally, the tissues should be firm and healthy (Fig 2-7). When the tissues are not healthy, retention and stability of the dentures may be compromised. If the tissues are inflamed, then the cause of the inflammation should be determined. Common causes of inflammation of the oral tissues are trauma and candidal infection. Oral manifestations of blood dyscrasias (e.g. iron-deficiency anaemia, leukaemia) may also be present. If salivary flow has diminished, the mucosa will feel dry and this will affect comfort and denture retention. Areas of thin mucosa offer poor support for a denture and may not be resistant to trauma. Management strategies for this situation are discussed in Chapter 7. Areas of mobile, flabby tissue should be noted, as these will compromise retention and stability. The presence of pathological conditions should also be checked. Common pathological conditions associated with denture-wearing include chronic candidal infection and denture-induced hyperplasia. The clinician should also bear in mind the possibility of neoplasia. This may be associated with chronic irritation due to overextended areas of a denture (Fig 2-8).

Fig 2-7 Healthy ridges free of pathology:(a) maxilla and (b) mandible.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses