Treatment Plans for Partially and Completely Edentulous Arches in Implant Dentistry

Carl E. Misch

Partially Edentulous Arches

To organize treatment plans in a consistent approach, a classification of patient conditions is necessary. There are more than 65,000 possible combinations of teeth and edentulous spaces; as a result, no universal agreement exists regarding the use of any one classification system. Numerous classifications have been proposed for partially edentulous arches. Their use allows the profession to visualize and communicate the relationship of hard and soft structures. This chapter reviews a classification for diagnosis and treatment planning for patients who are partially or completely edentulous and require implant prostheses. By using this classification, which the author first presented in 1985, the doctor is able to convey the dimensions of the bone available in the edentulous area and indicate the strategic position of the segment to be restored.1,2

History

Cummer,3 Kennedy,4 and Bailyn5 originally proposed the classifications of partially edentulous arches that are most familiar to the profession. These classifications were developed to organize removable partial denture (RPD) designs and concepts. Other classifications have also been proposed6–16 (including one by the American College of Prosthodontists), none of which has been universally accepted. The Kennedy classification, however, has been taught in most American dental schools.

The Kennedy classification divides partially edentulous arches into four classes.4 Class I has bilateral posterior edentulous spaces, class II has a unilateral posterior edentulous space, class III has an intradental edentulous area, and class IV has an anterior edentulous area that crosses the midline.

The Kennedy classification is difficult to use in many situations without certain qualifying rules. The eight Applegate rules are used to help clarify the system.13 They may be summarized in three general principles. The first principle is that the classification should include only natural teeth involved in the final prosthesis and follow rather than precede any extractions of teeth that might alter the original classification. This concept, for example, considers whether second or third molars are to be replaced in the final restoration. The second rule is that the most posterior edentulous area always determines the classification. The third principle is that edentulous areas, other than those determining the classification, are referred to as modifications and are designated only by their number. The extent of the modification is not considered.

Classification of Partially Edentulous Arches

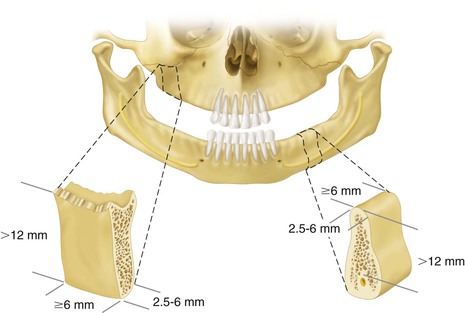

The implant dentistry bone volume classification developed by Misch and Judy in 1985 may be used to build on the four classes of partial edentulism described in the Kennedy–Applegate system.1,2 This facilitates communication of teeth positions and the primary edentulous sites among the large segment of practitioners already familiar with this classification, and it enables the use of common treatment methods and principles established for each class. The implant dentistry classification for partially edentulous patients by Misch and Judy also includes the same six available bone volume divisions (A, B, VB–w, C–w, C–h, and D) previously presented for edentulous areas. Other intradental edentulous regions that are not responsible for the Kennedy–Applegate class determination are not specified within the available bone section if implants are not considered in the modification region. However, if the modification segment is also included in the treatment plan, then it is listed followed by the available bone division it characterizes.

Treatment Planning: Class I

In class I patients, distal edentulous segments are bilateral and natural anterior teeth are present (Figure 19-1). The majority of these arches are only missing molars, and almost all have retained at least the anterior incisors and canines.17 Therefore, after restored to proper occlusal vertical dimension, the natural anterior teeth contribute to the distribution of forces throughout the mouth in centric relation occlusion. More importantly, when opposing natural teeth or in fixed implant prosthesis, they also permit excursions during mandibular movement to disclude the posterior implant–supported prostheses and protect them from lateral forces. However, many of these mandibular class I patients oppose a maxillary denture, in which case bilateral balance is more appropriate.

Class I patients are more likely to wear a RPD than class II or III patients because mastication and support of an opposing removable prosthesis is more difficult when not wearing the bilateral mandibular prosthesis. The posterior soft tissue–supported class I partial dentures are designed to either primarily load the edentulous regions or the natural anterior teeth. The clasp design, which places less force on the tooth (e.g., bar clasp including t, y rpi), places more force on the bone. The RPDs, which place more force on the abutment teeth (e.g., precision partial dentures), place less force on the bone. In either case, the removable prosthesis often accelerates the posterior bone loss. In addition, a partial denture that is not well designed or maintained distributes additional loads to abutment teeth and may even contribute to poor periodontal health. The combinations of these conditions lead to bone loss in the edentulous regions and poorer adjacent natural abutments.18–20 As a result, it is this author’s observation that long-term class I patients who have been wearing a RPD often exhibit division C ridges and mobile abutment teeth.

Class I patients often have mobile anterior teeth because long-term lack of bilateral posterior support caused by the wearing of a poorly fitting RPD, or none at all, has resulted in an overload to the remaining dentition. Therefore, these patients often require a posterior implant prosthesis to be independent from the mobile natural teeth. In addition, the occlusal scheme must accommodate the specific conditions of mobile anterior teeth. This requires increased implant support in the posterior segments compared with most class II or III patients, as well as greater attention and frequency for occlusal adjustments.

The treatment plan must consider the factors of force previously identified and relate them to the existing bilateral edentulous condition. Osteoplasty cannot be as aggressive in a class I patient to increase bone width compared with a class IV or fully edentulous patient with implants primarily in the anterior regions because of the opposing anatomical landmarks (maxillary sinus or mandibular canal). Augmentation procedures are often required to improve posterior bone volume, increase the implant surface area, and permit the fabrication of an independent implant restoration.

Financial concerns may require the staging of treatment over years. The posterior region with the greatest volume of bone usually is restored first if no bone grafting is required. In this manner, implants of greater size and surface area can resist the unilateral posterior forces while the patient awaits future treatment. If many years pass before implants are to be inserted in the lesser available bone, then continued resorption may require augmentation before reconstruction.

If both posterior segments require bone grafting, the patient is encouraged to have both posterior segments augmented at the same time. In this way, the autologous portion of the graft may be harvested and distributed to both posterior regions, decreasing the number of surgical episodes for the patient.

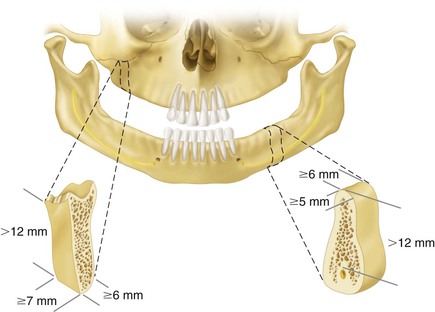

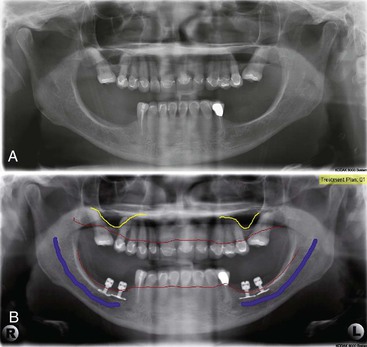

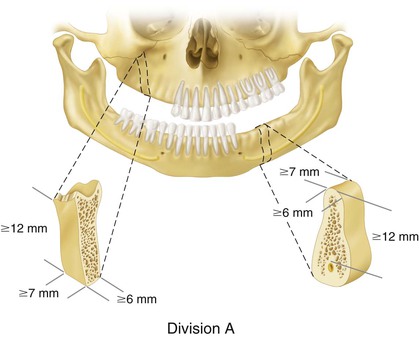

Division A Treatment Plans

When patients are placed in a class I, division A category, an independent implant–supported fixed prosthesis is usually indicated. Two or more endosteal root form implants are required to replace molars with independent prostheses (Figure 19-2). The greater the number of teeth missing, the larger the size or number of implants required. Posterior available bone is limited in height by the mandibular canal in the mandible or the maxillary sinus in the maxilla. The first premolar positioned implants must avoid encroachment on the apex of the canine root and yet avoid the maxillary sinus in the maxilla. In the mandible, the first premolar implant is placed most often anterior the mental foramen and the anterior loop when present (Figure 19-3).

Division B Treatment Plans

Class I, division B patients have narrow bone in posterior edentulous spaces and anterior natural teeth (Figure 19-4). A fixed prosthesis is also indicated in these categories. Available bone height is restricted by the mandibular canal or maxillary sinus. Therefore, osteoplasty to increase bone width has limited applications. Endosteal small-diameter root form implants may be placed in the mandibular posterior division B edentulous ridge. If narrow-diameter root forms are used, then a greater number is usually required than for the division A root form size. The use of one implant for every missing tooth root with no cantilever is recommended.

A patient missing molars and both premolars in the mandible requires at least three division B root forms (distal of the first molar, first premolar, and mesial of first molar [the second molar is not replaced]), and this may be the foundation of an independent fixed partial denture (FPD) in the mandible, depending on the other stress factors. In the maxilla, the second molar is usually replaced, and four division B root form implants are required (first premolar, second molar, first molar, second premolar). If stress factors are too great (as a result of parafunction) or bone density is poor (as in the maxilla), then the division B bone should be augmented to division A before larger-diameter implant insertion. The anterior teeth in class I patients should provide disclusion of the posterior implants during all excursions when opposing natural teeth or a fixed prosthesis.

Molar endosteal implants should not be rigidly cross-splinted to each other in a mandibular class I patient. Flexure of the mandible during opening and torsion during clenching may cause a rigid splint to exert lateral forces on the posterior implants. Therefore, independent restorations are indicated.

Another option in selected patients for division B bone may be a narrow plate form implant. These implants are usually used to replace a missing molar or molar and second premolar (when opposing a maxillary denture or low for factors). The plate form implant is often splinted to one or two nonmobile premolars in the final prosthesis. No lateral loads should be applied to the implant prosthesis when opposing natural teeth.

Division C Treatment Plans

When inadequate bone exists in height, width, length, or angulation or if crown height space (CHS) is equal to or greater than 15 mm, the practitioner must consider several options. The first treatment option is to not use implant support but rather to orient the patient toward a conventional removable partial prosthesis. However, although this condition is easiest to treat with a traditional soft tissue–borne restoration, bone loss will continue and can eventually compromise any restorative modality.

The second option is to use bone augmentation procedures. If the intent of the bone graft is to change a division C to a division A or B for endosteal implants, then at least some autogenous bone is indicated. Augmentation is used most often in the class I maxilla, where sinus grafts with a combination of allografts and autogenous bone are a predictable modality. Implants may be placed after the graft has created a division A ridge, and the treatment plan follows the options previously addressed.

In the mandible, the third option for the class I, division C patient is to place unilateral subperiosteal implants or disc implants above the canal (Figure 19-5). The disc or subperiosteal implant may support independent posterior fixed prostheses bilaterally or may be splinted to one or two premolars. As with the plate form implant, no lateral loads should be applied to the implant restoration when opposing natural teeth.

A division A root form implant may usually be inserted in the first premolar position even when the rest of the posterior ridge is division C–h. A fourth treatment option in the mandible is nerve repositioning and endosteal implants in class I patients who are poor candidates for bone augmentation or subperiosteal implants. Risks of long-term paresthesia exist that may include hyperesthesia and pain. Reports in the literature also concern dysesthesia and fracture of the severely atrophic mandible.21,22

The placement of disc implants or nerve repositioning in the division C mandible still must compensate for the increased crown height and resultant unfavorable forces to any cantilever or angled force. Therefore, it is important that only long axis forces are placed on the prosthesis and anterior guidance distributes bilateral forces away from the posterior restorations.

Division D Treatment Plans

Class I, division D usually occurs most often in the long-term edentulous maxilla (Figure 19-6). The ridge is division D because the sinus expands more than the crest of the ridge resorbs. A sinus graft is usually performed before implant placement. These augmentation procedures are very predictable. Class I, division D ridges are rarely found in a mandibular partially edentulous patient. When observed, the most common causes are from trauma or surgical excision of neoplasms. These patients often need autogenous bone onlay grafts to improve implant success and prevent pathologic fracture before prosthodontic reconstruction. After the graft is mature and the available bone improved, the patient is evaluated and treated in a manner similar to other patients with favorable bone volume.

Another option in a class I, division D mandible is to extract the anterior teeth, place five or six implants in the anterior region between the mental foramen, and cantilever a fixed prosthesis to restore the complete dentition. This option is more often used when the anterior teeth are periodontally compromised, the patient desires a fixed restoration, and the anterior mandible has an ovoid to tapering residual ridge form.

Treatment Planning: Class II

Kennedy–Applegate class II partially edentulous patients are missing teeth in one posterior segment (Figure 19-7). These patients are often able to function without a removable restoration and are less likely to tolerate or overcome the minor complications of wearing the prosthesis. As a result, they are not as likely to wear a removable restoration. The available bone is therefore often adequate for endosteal implants even when long-term edentulism has been present. Endosteal implants with minimum osteoplasty in the mandible are a common modality in these patients, who are class II, division A or B types.23,24 However, in the maxilla, the sinus usually expands and the local bone density may be decreased.

Because the patient is less likely to wear the RPD, the opposing natural teeth have often extruded into the posterior edentulous region. The occlusal plane and tipped or extruded teeth should be closely evaluated and restored as indicated to provide a favorable environment in terms of occlusion and forces distribution. It is not unusual to require extraction of the second molar, endodontics, crown lengthening and a crown of the first molar, and enameloplasty for the second premolar.

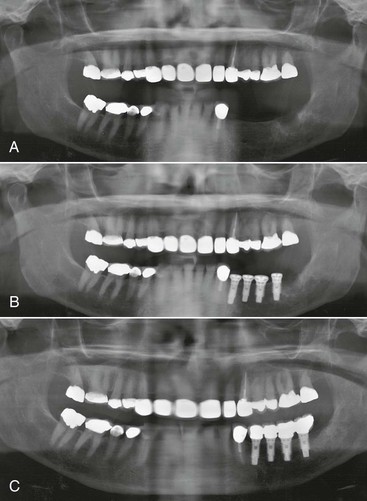

Division A Treatment Plans

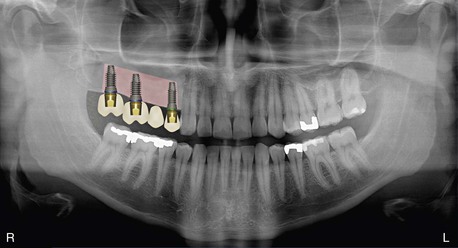

When patients are placed in a class II, division A category, an independent implant–supported fixed prosthesis is usually indicated. Two or more endosteal root form implants are required to replace molars with independent prostheses. The greater the number of teeth missing, the larger the size or number of implants required. Posterior available bone is limited in height by the mandibular canal in the mandible or the maxillary sinus in the maxilla. The first premolar-positioned implants must not encroach on the apex of the canine root while still avoiding the anterior loop of the mandibular canal or maxillary sinus (Figure 19-8). When parafunction is present, one implant for each tooth missing should be considered (Figure 19-9).

Division B Treatment Plans

Class II, division B patients have narrow bone in one posterior edentulous space and anterior natural teeth. A fixed prosthesis is also indicated in these categories. Available bone height is restricted by the mandibular canal or maxillary sinus. Therefore, osteoplasty to increase bone width has limited applications. Endosteal small-diameter root form implants may be placed in the mandibular posterior division B edentulous ridge. If narrow-diameter root forms are used, then a greater number than for the division A ridge is indicated, and the use of one implant for every missing tooth root with no cantilever is recommended when stress factors are greater than use (e.g., parafunction, opposing an implant prosthesis). Remember, in the mandible, the second molar is rarely replaced. In the division B maxillary ridge, bone spreading or augmentation is more usual because the density of bone is more often poor.

When force factors are low (i.e., older female patient, opposing a denture, limited parafunction), a plate form implant may be used to replace a molar or second premolar and molar in the mandible. This implant is usually splinted to a nonmobile posterior tooth.

A patient missing molars and both premolars requires additional implant support. Three division B root forms may be the foundation of an independent FPD in the mandible, depending on the other stress factors. If stress factors are too great (as a result of parafunction) or bone density is poor (as in the maxilla), then the division B bone should be augmented to division A before larger-diameter implant insertion (Figure 19-10). The anterior teeth in class II patients should provide disclusion of the posterior implants during all excursions.

Division C Treatment Plans

When inadequate bone exists in height, width, length, or angulation or if CHS is equal to or greater than 15 mm, the edentulous site is division C (Figure 19-11). This category has several options. In the mandible, the first treatment option is to not use implant support but to consider a posterior cantilevered FPD replacing one premolar-sized crown using two or three anterior teeth as abutment support. This is the easiest option and is strongly recommended when only molars are missing./>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses