19

Ophthalmic anaesthesia

Anaesthesia for ophthalmic surgery can be divided into the following areas:

- cataract surgery (usually elderly);

- squint surgery (usually children);

- corneal and vitreoretinal surgery;

- emergency surgery.

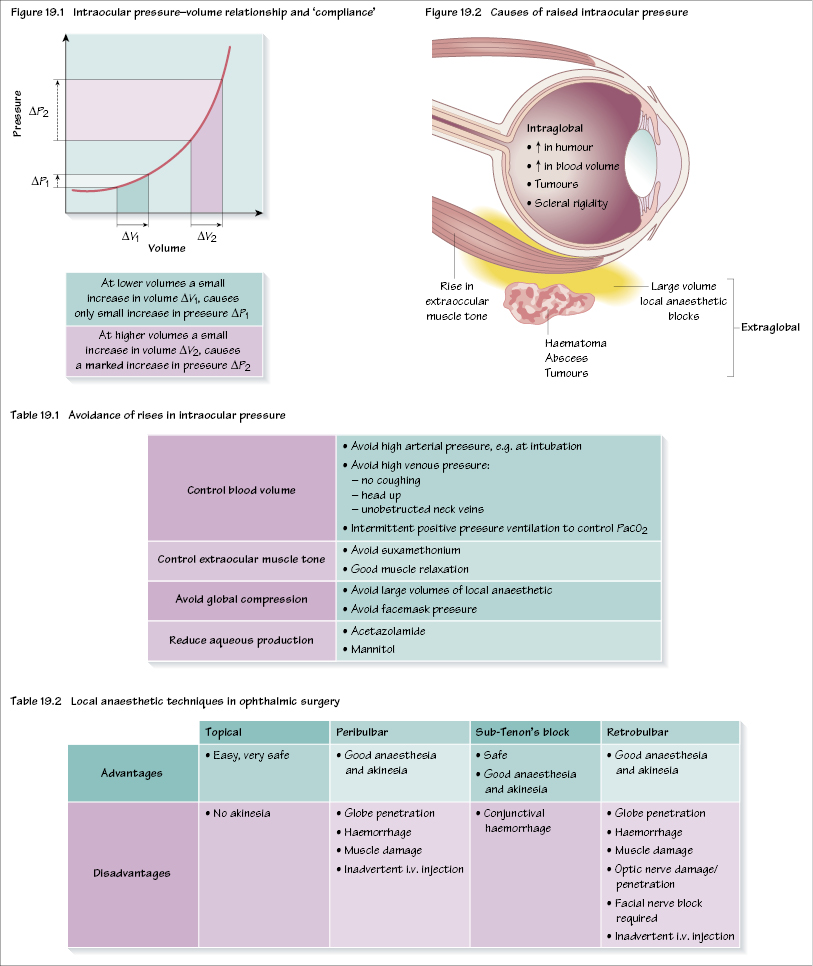

A key area in ophthalmic anaesthesia involves the factors that increase or lower intraocular pressure (IOP). The eye (like the brain) is a rigid structure that has very little ability to expand, therefore any increase in intraocular volume rapidly causes a marked increase in IOP. This pressure–volume or compliance relationship is shown in Figure 19.1.

The normal IOP is 10–20 mmHg. A rise in IOP from intraglobal causes (e.g. blood, aqueous) or from extrinsic pressure can cause IOP to rise to dangerous levels. In an intact eye, perfusion of the retina is put at risk if IOP exceeds retinal artery pressure. However, should a rise in IOP occur when the eye is open during surgery or during a penetrating eye injury it may cause the loss of intraorbital contents (e.g. vitreous/lens) etc. The factors that cause a raised IOP are shown in Figure 19.2. Preventing a rise in IOP is fundamental to good ophthalmic anaesthesia and strategies are shown in Table 19.1.

Cataract surgery

The essential requirements are anaesthesia of the conjunctiva together with a quiet eye, that is no rise in intraocular pressure. Some surgeons require akinesia too, necessitating additional anaesthesia to topical (surface) anaesthesia. The majority of these procedures are carried out under local anaesthesia, with patients spending only a couple of hours in hospital. There are a number of available techniques (Table 19.2).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses