Nutritional Aspects of Gingivitis and Periodontal Disease

• Describe the role nutrition plays in periodontal health and disease to a patient.

• List the effects of food consistency and composition in periodontal disease.

• Describe nutritional factors associated with gingivitis and periodontitis.

• Discuss components of nutritional education for a periodontal patient.

• List major differences between full liquid, mechanically altered, bland, and regular diets.

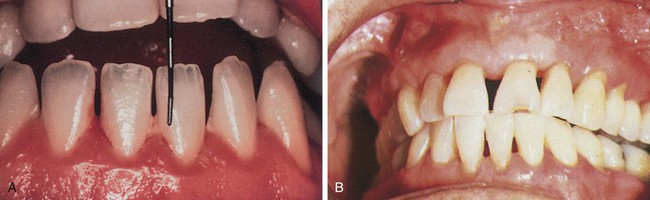

Gingivitis is characterized by inflammation, swelling, changes in contour or consistency, presence of plaque biofilm or calculus or both, no evidence of attachment loss, and bleeding on probing (Fig. 19-1, A). Connective tissue and bone support are intact. Gingivitis is often reversible with appropriate oral hygiene techniques. If left untreated, gingivitis can progress to periodontal disease.

Periodontal disease is a chronic, inflammatory, and infectious disease (see Fig. 19-1, B). It is the result of a loss of connective tissue and alveolar bone. Common findings are gingival bleeding, pain, infection, suppuration (formation or discharge of pus), tooth mobility, and tooth loss. Two targets for Healthy People 2020 are (1) to reduce the prevalence of moderate and severe periodontitis from nearly 13% to 11% in people ages 45-74 years and (2) to reduce the prevalence of tooth loss from periodontal involvement.1

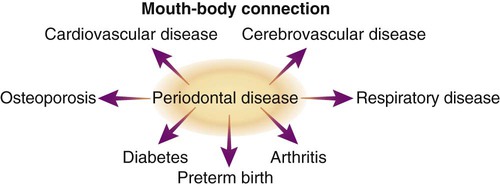

The inflammatory process of gingivitis and periodontal disease is affected by the host’s immune response—the body’s ability to protect itself from destructive periodontal pathogens and infection. Nutritional deficiencies, which may occur from adolescence through adulthood, can modify the body’s response to periodontal disease. Periodontal disease is the leading reason for tooth loss for individuals older than age 45 years. Bacteria associated with periodontal disease increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, premature births, respiratory infections, and uncontrolled diabetes (Fig. 19-2).

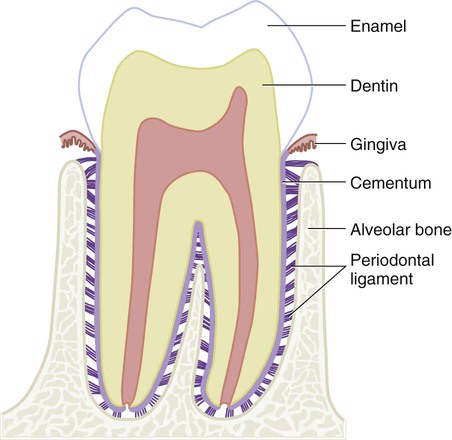

The involvement of nutrition in periodontal disease is not as clear as it is for dental caries. Predisposing, etiological, and contributing factors of periodontal disease are diverse; however, the primary initiating agent is plaque biofilm accumulation around teeth and gingiva. Nutrient deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances do not initiate periodontal disease, and megadoses of vitamin-mineral supplements do not cure or prevent periodontal disease. Indirectly, nutritional status may alter development, resistance, or repair of the periodontium (Fig. 19-3), which ultimately affects severity and extent of the disease. In addition, a patient’s health, medications, and food choices influence the properties of plaque biofilm and saliva. The buffering and antimicrobial effects of saliva are significant factors in periodontal disease. A change in composition or amount of saliva can influence development and maturation of plaque biofilm (see discussion of xerostomia in Chapter 20).

Physical Effects of Food on Periodontal Health

Food Composition

Normal growth and development of periodontal and oral mucosal tissues depend on sufficient intake of vitamin A (salivary glands, epithelial tissue), vitamin C (collagen, connective tissue), and vitamin B complex (epithelial and connective tissue). Calcification of the alveolus and cementum requires amino acids, calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, and magnesium. Maintenance of oral tissues and integrity of the host’s immune and repair responses requires sufficient amounts of vitamins A, C, D, and E; proteins; carbohydrates; calcium; iron; zinc; folic acid; and omega-3 fatty acids. Higher kilocalorie ranges also are indicated for increased metabolic needs for individuals with periodontal disease. (Refer to Chapters 4 through 12 for more descriptive information on the effects of specific nutrients on the periodontium.) Figure 19-4 depicts gingivitis-related malnutrition; note the inflammation, bulbous tissue, edema, and suppuration.

Nutritional Considerations for Periodontal Patients

Increased nutrients and energy are required by periodontal patients experiencing stress, tissue catabolism, or infection. A thorough assessment of the periodontal patient, as described in Chapter 21, provides valuable data needed to formulate a nutrition plan.

A medical and social history can indicate whether a patient is at risk of nutrient deficiencies because of alcoholism, anorexia, or other health problems. These patients would benefit from medical nutrition therapy by a RDN to normalize nutrient levels before treatment. Dietary education of all periodontal patients by the dental hygienist facilitates tissue repair and wound healing, improves resistance to infection, and reduces the number and severity of complications. Optimally, good nutritional status results in a shorter recovery and a more rapid return to health (Box 19-1).

Gingivitis

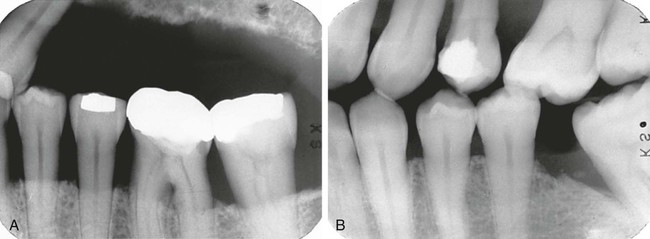

Gingivitis is a progressive inflammatory process beginning in the interdental papillae and advancing to the attached gingiva. The color of the gingiva varies from slight redness to a darker reddish blue. The gingiva bleeds easily and is either edematous and spongy or fibrotic (formation of fibrous tissue of the gingiva owing to chronic inflammation). The stippling of the gingiva disappears, and probing depths may increase without loss of attachment. Gingivitis is associated with a large accumulation of plaque biofilm and calculus on teeth (Fig. 19-5), which is exacerbated by frequent exposure to fermentable carbohydrates and retentive foods.

Chronic Periodontitis

Periodontitis involves clinical attachment loss (Fig. 19-6), separation of collagen fibers from the cementum and apical movement of the junctional epithelium onto the root surface. This destructive process results in bone loss. Inflammation is also present, affecting gingiva and other components of the periodontium. Severity of the gingival inflammation, recession, bone loss (Fig. 19-7), tooth mobility, and periodontal pocket formation varies according to duration of disease and the individual’s resistance level or immune response. It can be localized or generalized in the mouth possibly with purulent exudates, or drainage of fluids from the gingival sulcus.

Systemically, nutritional status determines immunocompetence of the periodontium. A deficiency of calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D can contribute to severity of bone loss (although the deficiency is not the primary cause). Recovery from periodontitis also is enhanced by the positive effect of adequate nutrient reserves and intake on the immune system. Adequate vitamin C reserves can help ensure wound healing.2 Nutrient intake exceeding the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) may not improve or accelerate the healing process and can be detrimental because of interference with other nutrients or drugs. With assistance from the dental professional, the patient can make dietary adjustments necessary to meet the stresses and increased nutrient requirements of the disease and to ensure optimal wound healing.

Nutritional recommendations for a patient with gingivitis can be adapted to meet the needs of a patient with periodontitis. Emphasis is placed on maintaining a nutritionally adequate diet; the Dietary Guidelines and MyPlate are valuable educational tools. The patient maintains a nutritionally adequate diet, while avoiding retentive foods; the dental hygienist analyzes food intake for the amount and frequency of fermentable carbohydrate intake (see Fig. 18-10 in Chapter 18). By working toward improving or eliminating etiological factors related to periodontitis, the healing process can minimize irreversible damage.

Periodontal Surgery

Preoperative

Postoperative

Dietary intake can be influenced by complications of anorexia, nausea, dysphagia, and oral discomfort. The texture of foods depends on extent of the surgery and symptoms of the patient. A full liquid diet may be required the first 1 to 3 days (Box 19-2). A full liquid diet provides food in a liquid form for patients who are unable to chew. It should consist of high-protein, high-kilocalorie fluids and semi-solid foods to promote optimal healing. Fluids can be drunk from a cup without the use of a spoon or straw. A full liquid diet is used only temporarily because nutrient and caloric value is usually inadequate. Any special diet modifications (e.g., low sodium, low fat) and patient preferences should be considered.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses