Chapter 18 Treatment Planning for the Edentulous Posterior Maxilla

Maxillary posterior partial or complete edentulism is one of the most common occurrences in dentistry. Seven percent of the adult population in the United States (12 million people) are missing all of their maxillary teeth and have at least some mandibular dentition—a condition that occurs 35 times more frequently than complete mandibular edentulism opposing maxillary teeth.1,2 In addition, 10.5% of the adult population has no teeth. Therefore 30 million people in the United States or 17.5% of the adult population are missing all of their maxillary teeth. In addition, 20% to 30% of the adult partially edentulous population older than 45 years of age is missing maxillary posterior teeth in one quadrant, and 15% of this age group is missing maxillary dentition in both posterior regions.2 In other words, approximately 40% of adult patients are missing at least some maxillary posterior teeth. Therefore the maxillary posterior region is one of the most common areas to be involved in an implant treatment plan to support a fixed or removable prosthesis.

The maxillary posterior edentulous region presents many unique and challenging conditions in implant dentistry. However, existing proven treatment modalities make procedures in this region as predictable as in any other intraoral region. Most noteworthy surgical methods include sinus grafts to increase available bone height, onlay grafting to increase bone width, and modified surgical approaches to insert implants in poorer bone density.3 Grafting of the maxillary sinus to overcome the problem of reduced vertical available bone has become a very popular and predictable procedure over the last decades. After the initial introduction by Tatum in the mid-1970s and the initial publication of Boyne and James in 1980, many studies have been published about sinus grafting with results higher than 90%.4–30

ANATOMICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE POSTERIOR MAXILLA

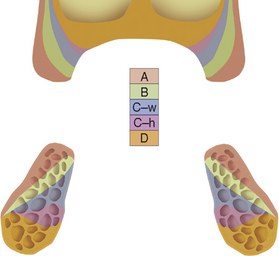

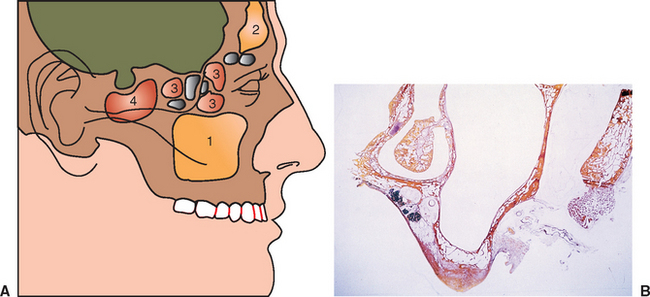

The dentate maxilla has a thinner cortical plate on the facial compared with the mandible. In addition, the trabecular bone of the posterior maxilla is finer than other dentate regions. The loss of maxillary posterior teeth results in an initial decrease in bone width at the expense of the labial bony plate. The width of the posterior maxilla decreases at a more rapid rate than in any other region of the jaws.27 The resorption phenomenon is accelerated by the loss of vascularization of the alveolar bone and the existing fine trabecular bone type. However, because the initial residual ridge is so wide in the posterior maxilla, even with a 60% decrease in the width of the ridge, adequate-diameter root form implants usually can be placed. Moreover, the ridge progressively shifts toward the palate until the ridge is resorbed into a medially positioned narrower bone volume.31 The posterior maxilla continues to progressively remodel toward the midline as the bone resorption process continues. This will result in the buccal cusp of the final restoration often being cantilevered facially to satisfy esthetic requirements at the expense of biomechanics in the moderate to severe atrophic ridges(Figure 18-1).

Special Considerations for the Posterior Maxilla

Poor Bone Density

In general, the bone quality is poorest in the edentulous posterior maxilla compared with any other intraoral region.32 A literature review of clinical studies from 1981 to 2001 reveals the poorest bone density may decrease implant loading survival by an average of 16% and has been reported as low as 40%.33 The cause of these failures is related to several factors. Bone strength is directly related to its density, and the poor density bone of this region is often 5 to 10 times weaker in comparison to bone found in the anterior mandible.34 Bone densities directly influence the percent of implant-bone surface contact, which accounts for the force transmission to the bone. The bone-implant contact is least in D4 bone compared with other bone densities. The stress patterns developed in poor bone density migrate farther toward the apex of the implant. As a result, bone loss is more pronounced and occurs also along the implant body, rather than only crestally as in other denser bone conditions. Type IV (D4) bone also exhibits the greatest biomechanical elastic modulus difference when compared with titanium under load.34 This biomechanical mismatch develops a higher strain condition to the bone, which may be in the pathologic overload range. As such, strategic choices to increase bone-implant contact are suggested.

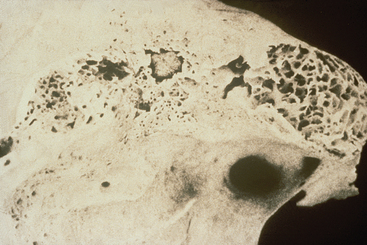

In the posterior maxilla, the deficient osseous structures and an absence of cortical plate on the crest of the ridge further compromise the initial implant stability at the time of insertion (Figure 18-2). The labial cortical plate is thin and the ridge is often wide. As a result, the lateral cortical bone-implant contact to stabilize the implant is often insignificant. Therefore initial healing of an implant in Type IV bone is often compromised, and clinical reports indicate a higher initial healing success than with D2 or D3 bone.

ANATOMY

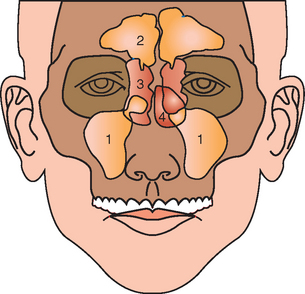

The maxillary sinuses were first illustrated and described by Leonardo Da Vinci in 1489 and later documented by the English anatomist Nathaniel Highmore in 1651.35 The maxillary sinus—or antrum of Highmore—lies within the body of the maxillary bone and is the largest and first to develop of the paranasal sinuses (Figure 18-3). Adult maxillary sinuses are pyramid-shaped, air-filled cavities that are bordered by the nasal cavity. There is much debate about the actual function of the maxillary sinus. Possible theorized roles of the sinus include weight reduction of the skull, phonetic resonance, participation of warming and humidification of inspired air, and olfaction. A biomechanical adaptation of the maxillary sinus directs forces away from the orbit and cranial cavity when a blow is delivered to the midface.

Expansion of the Maxillary Sinus

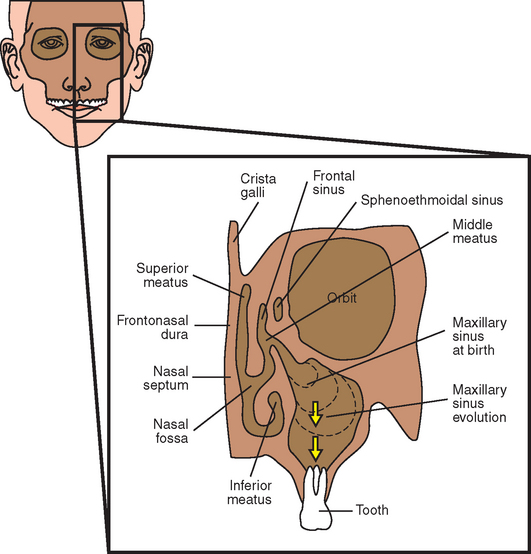

A primary pneumatization occurs at about 3 months of fetal development by an outpouching of the nasal mucosa within the ethmoid infundibulum. At that time, the maxillary sinus is a bud situated at the infralateral surface of the ethmoid infundibulum between the upper and middle meatus.36 Prenatally, a secondary pneumatization occurs. At birth, the sinus is still an oblong groove on the mesial side of the maxilla just above the germ of the first deciduous molar.36

At birth, the sinus cavities are filled with fluid. Postnatally and until the child is 3 months old, the growth of the maxillary sinus is closely related to the pressure exerted by the eye on the orbit floor, the tension of the superficial musculature on the maxilla, and the forming dentition. As the skull matures, these three elements influence its three-dimensional development. At 5 months, the sinus appears as a triangular area medial to the infraorbital foramen.37,38

During the child’s first year, the maxillary sinus expands laterally underneath the infraorbital canal, which is protected by a thin bony ridge. The antrum grows apically and progressively replaces the space formerly occupied by the developing dentition. The growth in height is best reflected by the relative position of the sinus floor. At 12 years of age, pneumatization extends to the plane of the lateral orbital wall, and the sinus floor is level with the floor of the nose. During later years, pneumatization spreads inferiorly as the permanent teeth erupt. The adult sinus has a volume of approximately 15 mL (34 × 33 × 23 mm). The main development of the antrum occurs as the permanent dentition erupts and pneumatization extends throughout the body of the maxilla and the maxillary process of the zygomatic bone. Extension into the alveolar process lowers the floor of the sinus about 5 mm. Anteroposteriorly, the sinus expansion corresponds to the growth of the midface and is completed only with the eruption of the third permanent molars when the young person is about 16 to 18 years of age.35–39

In the adult, the sinus appears as a pyramid of four bony walls, the base of which faces the lateral nasal wall and the apex of which extends toward the zygomatic bone (Figure 18-4). The floor of the maxillary sinus cavity is reinforced by bony or membranous septa joining the medial or lateral walls with oblique or transverse buttresslike webs. They develop as a result of genetics and stress transfer within the bone over the roots of teeth. These have the appearance of reinforcement webs in a wooden boat and rarely divide the antrum into separate compartments. These elements are present from the canine to the molar region and tend to disappear in the maxilla of the long-term edentulous patient when stresses to the bone are reduced. Karmody found that the most common oblique septum is located in the superior anterior corner of the sinus or infraorbital recess (which may expand anteriorly to the nasolacrimal duct).40 The medial wall is juxtaposed with the middle and inferior meatus.

Although the maxillary sinus maintains its overall size while the teeth are present, an expansion phenomenon of the maxillary sinus occurs with the loss of posterior teeth.37 The antrum expands in both inferior and lateral dimensions. This expansion may even invade the canine eminence region and proceed to the lateral piriform rim of the nose. The dimension of available bone height of the posterior maxilla is greatly reduced as a result of dual resorption from the crest of the ridge and pneumatization of the sinus after the loss of teeth. The sinus expansion is more rapid than the crestal bone height changes. As a result of the inferior sinus expansion, the amount of available bone in the posterior maxilla greatly decreases in height (Figure 18-5).

After periodontal disease, tooth loss, and sinus expansion, frequently less than 10 mm remain between the alveolar ridge crest and the floor of the maxillary sinus, resulting in inadequate bone quantity for implant placement. A limited review of the literature reveals implants that were 9 mm or less in height may have a 16% lower survival rate compared with those implants longer than 10 mm.33 Therefore the height of bone is of primary importance for predictable implant support. This limited dimension is compounded by the decrease in bone density and the problem of the resultant medial posterior position of the ridge after resorption of bone width. As a result, failure and complications in the long term of many endosteal implant systems are reported.

Implant Treatment Plans for the Posterior Maxilla

High Occlusal Forces

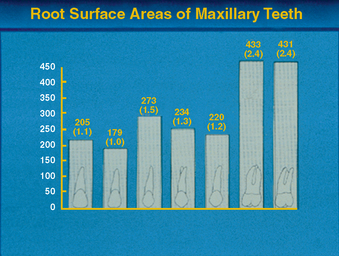

The occlusal forces in the posterior region are greater than in the anterior regions of the mouth. Studies have shown that the maximum bite force in the anterior region ranges from 35 to 50 lb/in2. The bite force in the molar region of a dentate person ranges from 200 to 250 lb/in2. As a consequence, the maxillary molars of the natural teeth have 200% more surface area than even the premolars and are significantly wider in diameter (Figure 18-6).3 Both these features reduce the stress to bone, which also reduces the strain of the bone. Following this natural selection, implant support should be greater in the posterior molar region than any other area of the mouth.3 Therefore the decrease in bone quantity and quality and increased forces should be considered in the treatment plan of this region of the mouth.41

Implant Size

Implant treatment plans should attempt to simulate the conditions found with natural teeth in the posterior maxilla. Because stresses occur primarily at the crestal region, biomechanical designs of implants to minimize their noxious effects should be implemented.41 Implant diameter is an effective method to increase surface area at the crestal region.41,42 Ideally, Division B implants are not used in the posterior maxilla. A 12-year retrospective study from 1982 to 1994 of 653 sinus grafts performed by the author revealed 14 implant failures. Eight implant failures were caused by implant fracture at the neck of smaller-diameter implants. Therefore implants of at least 4 mm in diameter are suggested, and 5-mm implants are encouraged in the molar region.

Implant Number

Implant number is an excellent method to decrease crestal stresses. As a general rule in this area, one implant for each missing tooth is indicated (Figure 18-7). Implants should always be splinted together to reduce stresses to the bone. If stress factors are magnified, two implants for each missing molar are suggested.

Implant Design

Implant design can increase surface area of support. A threaded design implant has 30% to 200% greater surface area compared with a cylinder implant of the same size. Although more difficult to place, the threaded implant in poorer density bone is strongly encouraged. Biomechanical aspects of thread designs affect the total increase in the surface area (i.e., thread pitch, shape, and depth).41

Roughened surface conditions or hydroxyapatite coating on the implant have been shown to increase the rate of osseous adaptation to implants, provide greater initial rigid fixation, increase the surface of bone contact and amount of lamellar bone, and give relative greater strength of the coronal bone around the roughened surface implants when compared with machined or smooth titanium implants.43–45 Therefore coatings or roughened surfaces are suggested in the compromised D3/D4 bone density.

TREATMENT HISTORY

Treatment of the Posterior Maxilla—Literature Review

In the late 1960s, Linkow reported that the blade-vent implant could be blunted and the maxillary sinus membrane slightly elevated to allow implant placement “into” the sinus in the posterior maxilla.55 This technique required the presence of at least 7 mm of vertical bone height below the antrum. For long-term predictable results, vertical bone height of at least 10 mm for D3 bone in the posterior maxilla has been clinically determined to be necessary when the diameter is 4 mm or more. Because the posterior maxilla often has D3 or D4 bone, implants of traditional design should have even greater height requirements.

Geiger reported that ceramic implants placed through the maxillary sinus floor could heal and stabilize without complication.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses