Diseases of the Blood and Blood-forming Organs

The hematologic disorders discussed in the following section are grouped, for ease of consideration, according to the cell type involved. No attempt is made to describe every known blood disease or even all the common ones. The sole criterion for inclusion in this section is the occurrence of oral manifestations and their obvious dental implications.

Diseases Involving Red Blood Cells

Anemia

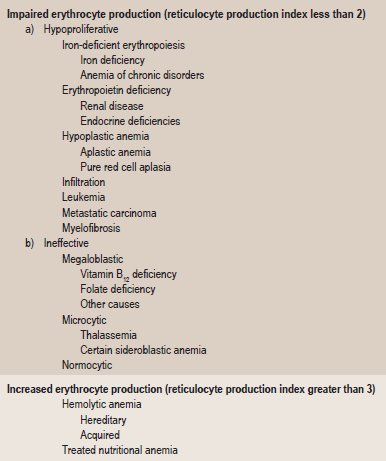

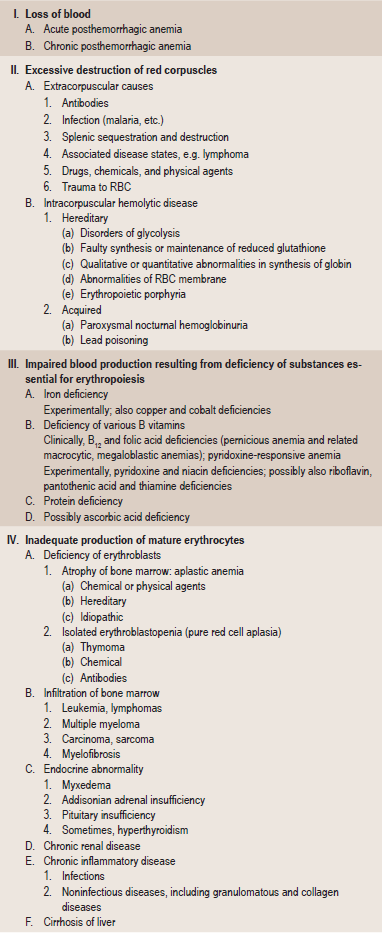

Anemia is defined as an abnormal reduction in the number of circulating red blood cells, the quantity of hemoglobin and the volume of packed red cells in a given unit of blood. The etiologies of the condition are extremely varied, and the classification presented in Table 18-1 based upon causes has been offered by Wintrobe.

Table 18-1

Etiologic classification of the anemia

Modified from MM Wintrobe: Clinical Hematology. 8th ed. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, 1981.

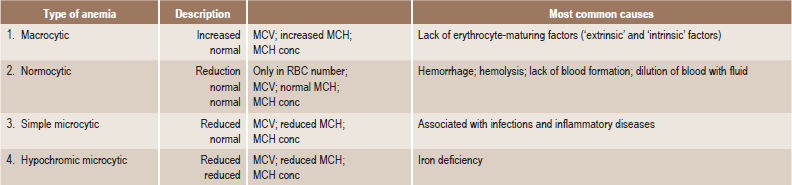

In addition to this etiologic classification, a morphologic classification (Table 18-2) has been found of great value. It expresses the characteristic changes in the size and hemoglobin content of the red blood cell and thus acts as a guide to treatment. A recent classification based on cellular kinetic parameters was suggested (Table 18-3).

Table 18-2

Morphologic classification of the anemia

MCV = mean corpuscular volume (Volume/RBC).

MCH = mean corpuscular hemoglobin (Hb/RBC).

MCH conc = mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (Hb/Vol).

Pernicious Anemia: (Vitamin B12 deficiency, Addisonian anemia, Biermer anemia, Hunter-Addison anemia, Lederer anemia, Biermer-Ehrlich anemia, Addison-Biermer disease)

Clinical Features

Pernicious anemia is rare before the age of 30 years and increases in frequency with advancing age. In the United States, males are affected more commonly than females; in other countries, notably Scandinavia, females are more commonly affected. No apparent racial predilection is noticed.

Oral Manifestations

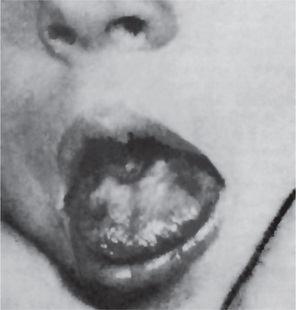

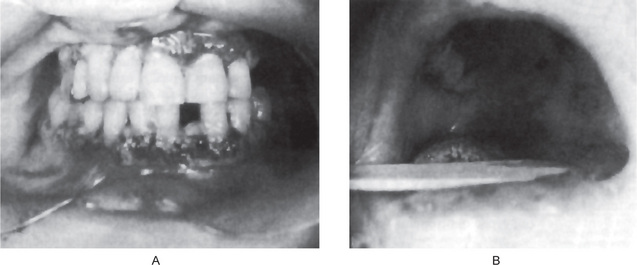

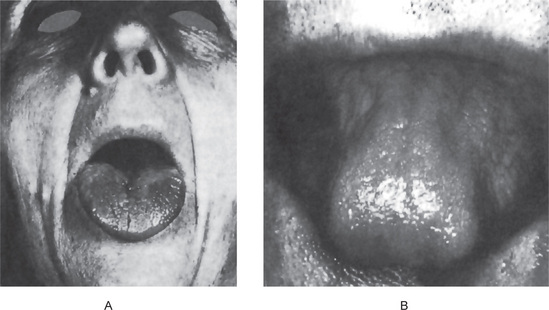

The tongue is generally inflamed, often described as ‘beefy red’ in color, either in entirety or in patches scattered over the dorsum and lateral borders (Fig. 18-1). In some cases, small and shallow ulcers — resembling aphthous ulcers — occur on the tongue. Characteristically, with the glossitis, glossodynia and glossopyrosis, there is gradual atrophy of the papillae of the tongue that eventuate in a smooth or ‘bald’ tongue which is often referred to as Hunter’s glossitis or Moeller’s glossitis and is similar to the ‘bald tongue of Sandwith’ seen in pellagra. Loss or distortion of taste is sometimes reported accompanying these changes. The fiery red appearance of the tongue may undergo periods of remission, but recurrent attacks are common. On occasion, the inflammation and burning sensation extend to involve the entire oral mucosa but, more frequently, the rest of the oral mucosa exhibits only the pale yellowish tinge noted on the skin. Millard and Gobetti have emphasized that a nonspecific persistent or recurring stomatitis of unexplained local origin may be an early clinical manifestation of pernicious anemia. Not uncommonly the oral mucous membranes in patients with this disease become intolerant to dentures.

Figure 18-1 Pernicious anemia. The tongue is inflamed and painful in each case, and there is beginning of atrophy of the papillae in (A) and advanced atrophy in (B) (Courtesy of Dr Boynton H Booth and Dr Stephen F Dachi).

Farrant and Boen and Boddington have reported that cells from buccal scrapings of patients with pernicious anemia presented nuclear abnormalities consisting of enlargement, irregularity in shape and asymmetry. These were postulated to be due to a reduced rate of nucleic acid synthesis with a reduced rate of cell division. These epithelial cell alterations are rapidly reversible after administration of vitamin B12.

Laboratory Findings

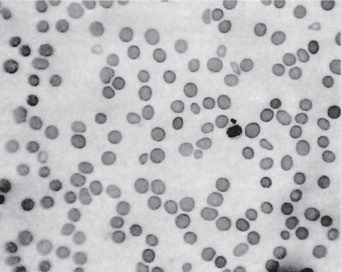

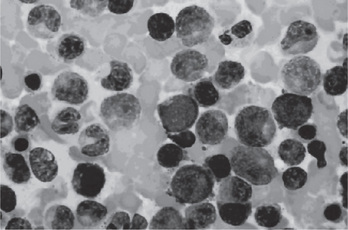

This chronic disease often exhibits periods of remission and exacerbation, and the blood changes generally parallel these clinical states. The red blood cell count is seriously decreased, often to 1,000,000 or less per cubic millimeter. Many of the cells exhibit macrocytosis; this, in fact, is one of the chief characteristics of the blood in this disease, although poikilocytosis, or variation in shape of cells, is also present (Fig. 18-2). The hemoglobin content of the red cells is increased, but this is only proportional to their increased size, since the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration is normal. A great many other red blood cell abnormalities have been described, particularly in advanced cases of anemia, including polychromatophilic cells, stippled cells, nucleated cells, Howell-Jolly bodies and Cabot’s rings punctate basophilia. Leukocytes are also often remarkably reduced in number, but are increased in average size, in number of lobes to the nucleus (becoming the so-called macropolycytes) and anisopoikilocytosis. Mild to moderate thrombocytopenia is noticed. Coexistent iron deficiency is common because achlorhydria prevents solubilization of dietary ferric iron from foodstuffs. Striking reticulocyte response and improvement in hematocrit values after parenteral administration of cobalamin is characteristic.

The bone marrow biopsy and aspirate usually are hypercellular and show trilineage differentiation. Erythroid precursors are large and often oval. The nucleus is large and contains coarse motley chromatin clumps, providing a checkerboard appearance. Nucleoli are visible in the more immature erythroid precursors. Imbalanced growth of megakaryocytes is evidenced by hyperdiploidy of the nucleus and the presence of giant platelets in the smear. Lymphocytes and plasma cells are spared from the cellular gigantism and cytoplasmic asynchrony observed in other cell lineages. The bone marrow histology is similar in both folic acid and cobalamin deficiency.

Celiac Sprue: (Celiac disease, nontropical sprue, gluten-sensitive enteropathy, Gee-Herter disease)

Oral Manifestations

The oral changes in sprue are similar to those of pernicious anemia and have been described by Adlersberg from observation of 40 cases. There may be a severe glossitis with atrophy of the filiform papillae, although the fungiform papillae often persist for some time on the atrophic surface. Painful, burning sensations of the tongue and oral mucosa are common, and small, painful erosions may occur. These severe oral manifestations are seldom absent in cases of sprue (Fig. 18-3). Tyldesley has reviewed this problem recently and concluded that there is an association between recurrent oral ulceration, or recurrent aphthous ulcers, and celiac disease and that proper dietary treatment leads to remission of the oral lesions.

Laboratory Findings

The blood and bone marrow changes are often identical with those of pernicious anemia and include a macrocytic anemia and leukopenia. Hypochromic microcytic anemia occasionally occurs. A low serum iron level is common. The prothrombin time (PT) might be prolonged because of malabsorption of vitamin K. The patients do not usually exhibit achlorhydria, nor is the ‘intrinsic’ factor absent.

Aplastic Anemia

Clinical Features

The patients usually complain of severe weakness with dyspnea following even slight physical exertion and exhibit pallor of the skin. Numbness and tingling of the extremities and edema are also encountered due to anemia. Petechiae in the skin and mucous membranes occur, owing to the platelet deficiency, while the neutropenia leads to a decreased resistance to infection.

Oral Manifestations

Petechiae purpuric spots or frank hematomas of the oral mucosa may occur at any site, while hemorrhage into the oral cavity, especially spontaneous gingival hemorrhage, is present in some cases. Such findings are related to the blood platelet deficiency (Fig. 18-4). As a result of the neutropenia there is a generalized lack of resistance to infection, and this is manifested by the development of ulcerative lesions of the oral mucosa or pharynx. These may be extremely severe and may result in a condition resembling gangrene because of the lack of inflammatory cell response.

Thalassemia: (Cooley’s anemia, Mediterranean anemia, erythroblastic anemia)

Two other forms of thalassemia major that represent α-thalassemia also exist. These are:

• Hemoglobin H disease, which is a very mild form of the disease in which the patient may live a relatively normal life.

• Hemoglobin Bart’s disease, with hydrops fetalis, in which the infants are stillborn or die shortly after birth.

Clinical Features

In high-risk areas (i.e. Greek and Italian islands), 10% of the population may have homozygous β-thalassemia; 5% in Southeast Asian populations; and 1.5% in African and American black populations. The onset of the severe form of the disease (homozygous β-thalassemia) occurs within the first two years of life, often in the first few months. Siblings are commonly affected. The child has a yellowish pallor of the skin and exhibits fever, chills, malaise and a generalized weakness. Splenomegaly and hepatomegaly may cause protrusion of the abdomen. The face often develops mongoloid features due to prominence of the cheek bones, protrusion or flaring of the maxillary anterior teeth, and the depression of the bridge of the nose which gives rise to the characteristic rodent facies. The child does not appear acutely ill, but the disease follows an ingravescent course which is often aggravated by intercurrent infection. Some patients; however, die within a few months, especially when the disease is manifested at a very early age. Logothetis and his associates have shown that the degree of cephalofacial deformities in this disease (including prominent frontal and parietal bones, sunken nose bridge, protruding zygomas and mongoloid slanting eyes) is closely related to the severity of the disease and the time of institution of treatment.

Thalassemia minor (thalassemia trait) is generally without clinical manifestations.

Radiographic Features

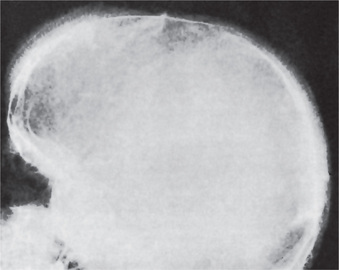

The skeletal changes in thalassemia are most striking and have been thoroughly described by Caffey. A frequent finding in rib has been referred to as the rib-within-a-rib appearance and is noted particularly in the middle and anterior portions of the ribs. The finding consists of a long linear density within or overlapping the medullary space of the rib and running parallel to its long axis. In the skull, there is extreme thickening of the diploe (medulla), the inner and outer plates (cortices) become poorly defined, and the trabeculae between the plates become elongated, producing a bristle like crew-cut or hair-on-end appearance of the surface of the skull (Fig. 18-5). Because of the lack of hematopoietic marrow, the occipital bone usually is not involved.

Treatment

There is no treatment for this form of anemia. The administration of liver extract, iron or vitamin B6 is fruitless. Blood transfusions do provide temporary remissions. Bone marrow transplantation may be a definitive treatment option, but long-term results from transplants already performed are not available. The disease is usually fatal, although mild forms which are compatible with life apparently exist. Generally, the earlier in infancy the disease occurs, the more rapidly it proves fatal. Death is generally due to intercurrent infection, cardiac damage as a result of anoxia, or liver failure.

Sickle Cell Anemia: (Sickle cell disease)

Oral Manifestations

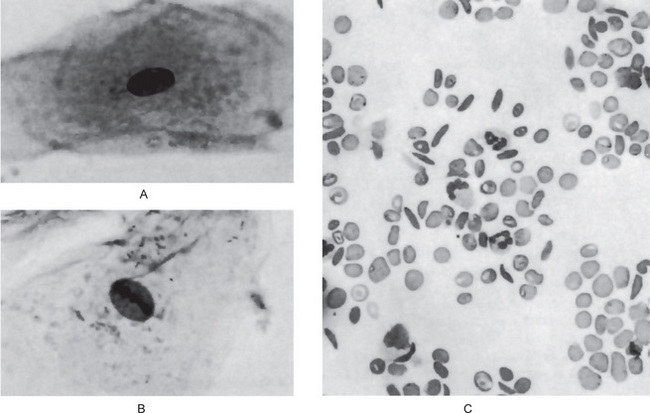

Goldsby and Staats have reported morphologic alterations in the nuclei of epithelial cells in scrapings of the oral mucosa in 90% of all studied cases of patients with homozygous sickle cell disease. These changes were chiefly nuclear enlargement, binucleation and an atypical chromatin distribution. These changes are similar to those that have been reported occurring in pernicious anemia and sprue (Fig. 18-6A, B).

Laboratory Findings

On the blood smear, typical sickle-shaped red blood cells are commonly seen, although they are present also in cases of the sickle trait without clinical evidence of the disease (Fig. 18-6C). Elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase and decreased levels of haptoglobin confirm the presence of hemolysis. Hemoglobin electrophoresis can be done to differentiate homozygous from heterozygous.

Treatment

Treatment strategies include the following five goals:

• Management of vaso-occlusive crisis

• Management of chronic pain syndromes

• Management of the chronic hemolytic anemia

• Prevention and treatment of infections

• Management of the complications and the various organ damage syndromes associated with the disease.

Because this is a lifelong disease, prognosis is not good. The goal is to achieve a normal lifespan with minimal morbidity.

Erythroblastosis Fetalis

Pathogenesis

• In some cases the mother may be unable to form antibodies even though immunized by the Rh-positive fetus.

• Even though the fetus is Rh-positive, transplacental transfer of the antigen does not occur, so that there is no maternal immunization.

• Immunization may occur, but its level is so low as to be clinically insignificant. Recent evidence has shown that, in general, women have a reduced immunologic responsiveness during pregnancy.

Oral Manifestations

Erythroblastosis fetalis may be manifested in the teeth by the deposition of blood pigment in the enamel and dentin of the developing teeth, giving them a green, brown or blue hue (Fig. 18-7). Ground sections of these teeth give a positive test for bilirubin. The stain is intrinsic and does not involve teeth or portions of teeth developing after cessation of hemolysis shortly after birth.

Iron Deficiency Anemia and Plummer-Vinson Syndrome: (Paterson-Brown-Kelly syndrome, Paterson-Kelly syndrome, sideropenic dysphagia)

The iron deficiency leading to this anemia usually arises through:

• Chronic blood loss (as in patients with a history of profuse menstruation

• Increased requirements for iron, as during infancy, childhood and adolescence and during pregnancy.

The Plummer-Vinson syndrome is one manifestations of iron-deficiency anemia and was first described by Plummer in 1914 and by Vinson in 1922 under the term ‘hysterical dysphagia’. Not until 1936; however, was the full clinical significance of the condition recognized. Ahlbom then defined it as a predisposition for the development of carcinoma in the upper alimentary tract. It is, in fact, one of the few known predisposing factors in oral cancer. It is thought that the depletion of iron-dependent oxidative enzymes may produce myasthenic changes in muscles involved in the swallowing mechanism, atrophy of the esophageal mucosa, and formation of webs as mucosal complications. It is also thought to be an autoimmune phenomenon as the syndrome is seen in association with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, pernicious anemia, celiac disease, and thyroiditis. Other factors such as nutritional deficiencies, genetic predisposition are thought to play roles in the causation of this disease.

Polycythemia

Secondary polycythemia is similar to primary polycythemia except that the etiology is known. Secondary polycythemia is caused due to absolute increase in red blood cell mass resultant to enhanced stimulation of red blood cell production. In general, the stimulus responsible for producing a secondary polycythemia is either bone marrow anoxia or production of an erythropoietic stimulating factor. Bone marrow anoxia may occur in numerous situations such as pulmonary dysfunction, heart disease, habitation at high altitudes or chronic carbon monoxide poisoning. Erythropoietic stimulatory factors include a variety of drugs and chemicals such as coal-tar derivatives, gum shellac, phosphorus, and various metals such as manganese, mercury, iron, bismuth, arsenic and cobalt. Some types of tumors such as certain brain tumors, liver and kidney carcinomas and the uterine myoma have also been reported associated with polycythemia. The mechanism for increased production of the red blood cells by these tumors is unknown, but has been postulated as due to elaboration of a specific factor which stimulates erythropoiesis.

Polycythemia Vera: (Polycythemia rubra vera, erythremia, Vaquez’s disease, Osler’s disease)

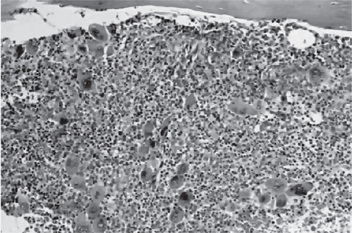

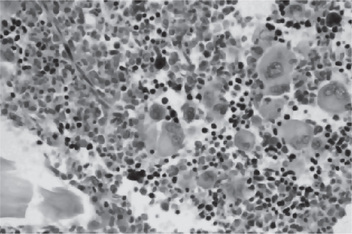

The bone marrow of patients with polycythemia vera shows normal and abnormal stem cells (Figs. 18-8, 18-9, and 18-10). The clonal proliferation of abnormal stem cells interfere with or suppress normal stem cell growth and maturation. Evidence indicates that the etiology of this panmyelosis is unregulated neoplastic proliferation. The cause of the stem cell transformation remains unknown.

Figure 18-8 Polycythemia vera, bone marrow aspirate. Increased number of both erythroid and myeloid precursors are seen. PV results in a panhyperplasia of marrow cell elements (Wright Giemsa, Oil).

Figure 18-9 Polycythemia vera, bone marrow core biopsy. Hypercellular, megakaryocytes are increased.

Figure 18-10 Polycythemia vera, megakaryocytes proliferation. This biopsy illustrates the proliferation of megakaryocytes in PV.

Clinical Features

Polycythemia vera often manifests itself primarily by headache or dizziness, weakness and lassitude, tinnitus, visual disturbances, mental confusion, slurring of the speech and inability to concentrate. The skin is flushed or diffusely reddened, as a result of capillary engorgement and high red cell mass, as though the patient were continuously blushing. This condition is most obvious on the head, neck and extremities, although the digits may be cyanotic. Increased red blood cell mass increases blood viscosity and decreases tissue perfusion, and also predisposes for thrombosis. If secondary polycythemia is secondary to hypoxia, patients can also appear cyanotic or may have acrocyanosis which is caused by sluggish blood flow through small blood vessels. The skin of the trunk is seldom involved. Splenomegaly is one of the most constant features of polycythemia vera, and the spleen is sometimes painful. Gastric complaints such as gas pains, belching and peptic ulcers are common, and hemorrhage from varices in the gastrointestinal tract may occur. Pruritus results from increased histamine levels released from increased basophils and mast cells and can be exacerbated by a warm bath or shower in up to 40% of patients. The disease is more common in men and usually occurs in middle age or later.

Laboratory Findings

Red blood cell mass and plasma volume can be measured directly using radiochromiumlabeled red blood cells which show an increase in mass with a normal or slightly decreased plasma volume. The red blood cell count is elevated and may even exceed 10,000,000 cells per cubic millimeter (Figs. 18-11). The red blood cells in patients with PV are usually normochromic normocytic. The hemoglobin content of the blood is also increased, often as high as 20 gm/dl, although the color index is less than 1.0. Because of the great number of cells present, both the specific gravity and the viscosity of the blood are increased.

Figure 18-11 Polycythemia vera, peripheral blood. It is often difficult to prepare a good peripheral blood smear in PV due to the increased viscosity of the blood. The red cells are crowded together (Wright Giemsa).

Leukocytosis is usual, as is a great increase in the number of platelets (400,000–800,000/dl) (Figs. 18-12, 18-13); in addition, the total blood volume is elevated through distention of even the smallest blood vessels of the body. The leukocyte alkaline phosphatase score is elevated (>100 U/L) in 70% of patients. There is usually hyperplasia of all elements of the bone marrow. Bleeding and clotting times are normal.

Diseases Involving White Blood Cells

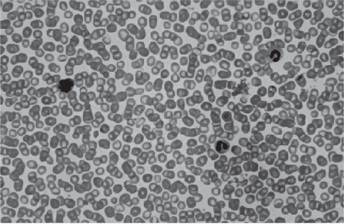

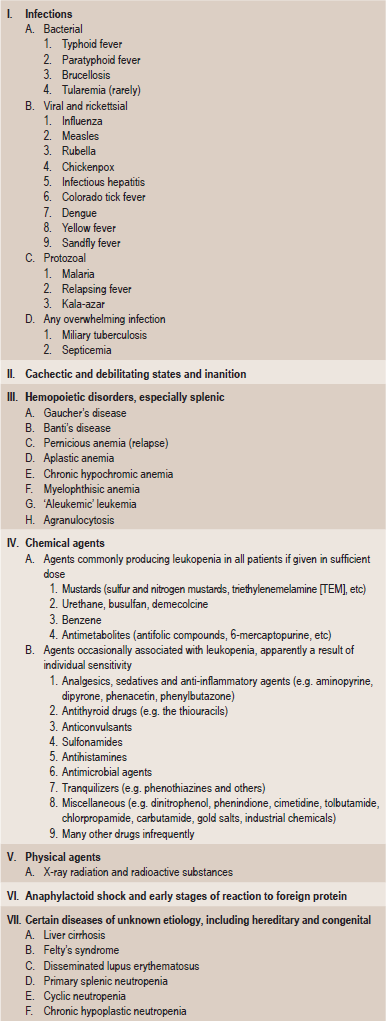

Leukopenia

Leukopenia is an abnormal reduction in the number of white blood cells in the peripheral blood stream. This decrease involves predominantly the granulocytes, although any of the cell types may be affected. The etiology of this particular sign of disease is extremely varied, but the classification shown in Table 18-4 has been devised by Wintrobe.

Table 18-4

Modified from MM Wintrobe: Clinical Hematology, 8th ed. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, 1981.

Agranulocytosis: (Granulocytopenia, agranulocytic angina, malignant leukopenia or neutropenia)

Etiology

The most common known cause of agranulocytosis is the ingestion of any one of a considerable variety of drugs (Table 18-5) and infections. Those compounds chiefly responsible for the disease are also those to which patients commonly manifest idiosyncrasy in the form of urticaria, cutaneous rashes and edema. For this reason and because often only small amounts of these drugs are necessary to produce the disease, it appears that the reaction may be an allergic phenomenon, although attempts to demonstrate antibodies in affected patients have not been successful. Moreover, in the case of some of the drugs, the disease occurs only after continued administration.

Table 18-5

Risks of agranulocytosis associated with select drugs

| Drug | RR | Excess risk |

| Antithyroid drugs | 97 | 5.3 |

| Macrolides | 54 | 6.7 |

| Procainamide | 50 | 3.1 |

| Aprindine | 49 | 2.7 |

| Dipyrone | 16 | 0.6 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 16 | 2.4 |

| Thenalidine | 16 | 2.4 |

| Carbamazepine | 11 | 0.6 |

| Digitalis | 2.5–9.9 | 0.1–0.3 |

| Indomethacin | 6.6 | 0.4 |

| Sulfonylureas | 4.5 | 0.2 |

| Corticosteroids | 4.1 | |

| Butazones | 3.9 | 0.2 |

| Dipyridamole | 3.8 | 0.2 |

| β-Lactams | 2.8 | 0.2 |

| Propranolol | 2.5 | 0.1 |

| Salicylates | 2.0 | 0.0006 |

From the International Aplastic Anemia and Agranulocytosis Study.

Barbiturates (including amobarbital and phenobarbital)

Sulfonamides (including sulfanilamide, sulfapyridine, sulfathiazole and sulfadiazine)

The mechanism that causes agranulocytosis is not understood completely. In drug-induced agranulocytosis, the drug may act as a hapten and induce antibody formation. Thus produced antibodies destroy the granulocytes or may form immune complexes which bind to the neutrophils and destroy them. Autoimmune neutropenia due to antineutrophil antibodies is seen in few cases.

Oral Manifestations

The oral lesions constitute an important phase of the clinical aspects of agranulocytosis. These appear as necrotizing ulcerations of the oral mucosa, tonsils and pharynx. Particularly involved are the gingiva and palate. The lesions appear as ragged necrotic ulcers covered by a gray or even black membrane (Fig. 18-12). Usually no purulent discharge is noticed. Significantly, there is little or no apparent inflammatory cell infiltration around the periphery of the lesions, although hemorrhage does occur, especially from the gingiva. In addition, the patients often manifest excessive salivation.

Cyclic Neutropenia: (Periodic neutropenia, cyclic agranulocytic angina, periodic agranulocytosis)

Clinical Features

This type of agranulocytosis may occur at any age, although the majority of cases have been reported in infants or young children. The symptoms are similar to those of typical agranulocytosis except that they are usually milder. The patients manifest fever, malaise, sore throat, stomatitis and regional lymphadenopathy, as well as headache, arthritis, cutaneous infection and conjunctivitis. In contrast to other types of primary agranulocytosis, rampant bacterial infection is not a significant feature (Table 18-6), presumably because the neutrophil count is low for such a short time. Entities closely mimic the clinical characteristics of cyclic neutropenia are variable, encompassing a wider spectra (Table 18-7).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Diseases Involving Red Blood Cells

. Diseases Involving Red Blood Cells . Diseases Involving White Blood Cells

. Diseases Involving White Blood Cells . Leukocytosis

. Leukocytosis . Diseases Involving Blood Platelets

. Diseases Involving Blood Platelets . Thrombocytasthenia

. Thrombocytasthenia . Diseases Involving Specific Blood Factors

. Diseases Involving Specific Blood Factors