Chapter 17 Esthetic Inlays and Onlays

Brief History of Clinical Development and Evolution of Esthetic Inlay and Onlay Procedures

Material Options

Commercial and indirect resin ceramic systems are listed in Table 17-1.

| PRODUCT NAME (PREVIOUS GENERATION) | PRODUCT NAME (CURRENT GENERATION) | MANUFACTURER |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Indirect Resin Systems | ||

| Visio Gem | Sinfony | 3M ESPE (St Paul, Minnesota) |

| Conquest | Sculpture Plus | Pentron Clinical (Wallingford, Connecticut) |

| Herculite Lab | Premise Indirect† | Kerr Corp. (Orange, California) |

| Concept* | Adoro‡ | Ivoclar (Schaan, Liechtenstein; Amherst, New York) |

| — | Cristobal+ | DENTSPLY International (York, Pennsylvania) |

| — | Gradia Indirect | GC America (Aslip, Illinois) |

| — | Tescera ATL | Bisco Inc. (Schaumberg, Illinois) |

| Commercial Ceramic Systems | ||

| — | Duceram LFC | DENTSPLY International (York, Pennsylvania) |

| — | Omega 900 | Vident (Brea, California) |

| — | Finesse or Finesse All Ceramic | DENTSPLY International (York, Pennsylvania) |

| — | Authentic | Jensen Dental (North Haven, Connecticut) |

| — | OPC | Pentron Clinical (Wallingford, Connecticut) |

| — | IPS Empress or IPS e.max | Ivoclar Vivadent (Schaan, Liechtenstein; Amherst, New York) |

* Concept was known as Isosit SR Inlay/Onlay outside North America.

† Premise Indirect was formerly belleGlass HP.

‡ Adoro is available only outside the United States.

Advantages

Some of the laboratory-fabricated resin systems have been in existence for 10 to over 22 years and have proven clinical efficacy. In recent years the physical properties and clinical performance of these materials have improved significantly (see Table 17-1). Although controversy exists as to which material, indirect composite or ceramic, provides the optimum long-term, durable, esthetic restoration, this author believes both indirect resin and ceramics can be used successfully. The final determination should rest with the clinician and be guided by personal preference. Numerous factors contribute to a high-quality restoration, and each must be examined with respect to the material, the fabrication process, and the clinical technique. Clearly, indirect composite materials are being fabricated with enhanced durability, wear resistance, and fit. The ultimate long-term success is a function of the materials used, the technique used by the clinician and the laboratory technician, and the patient’s care. In comparison to ceramic materials, inlay or onlay restorations composed of composite resin can generally be fabricated with greater ease in the laboratory. Resins also demonstrate improved wear compatibility against opposing tooth structure and can be repaired more easily intra-orally. For inlays, indirect composite seems to be currently the preferred material. For onlays the marketplace is weighted more toward ceramics than indirect composite but not by much. Numerous clinical trials have shown ceramic inlays or onlays to be viable restorations over time.

Treatment Planning for Esthetic Inlays or Onlays

Options

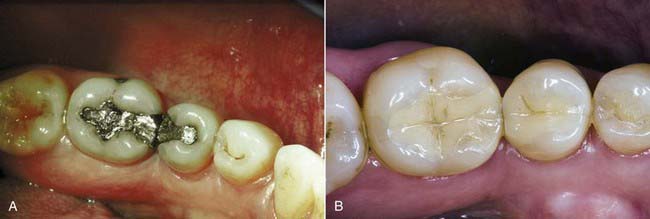

Figure 17-1 shows a very large amalgam in the first molar replacing a cusp. In the second molar there is an occlusal amalgam. In treatment planning for the second molar, which has some recurrent caries, the amalgam restoration can easily be replaced with a direct composite because of the relatively small size. The first molar has a very large amount of amalgam in need of replacement, so the decision is between going to a full-coverage crown, which would necessitate virtually removing the three remaining cusps, or removing all the old alloy plus any associated disease, leaving the three remaining cusps, and placing a bonded esthetic onlay. The latter is far more conservative because of the tooth reinforcement achieved by bonding to a significant amount of enamel and because the three cusps are preserved. Potentially this tooth may never need to be crowned. The case in Figure 17-2 shows the advantages, both conservative and esthetic, of adhesive onlay restorations.

FIGURE 17-1 Case demonstrating the advantages (conservative and esthetic) of adhesive onlay restorations.

Figure 17-3 shows four amalgams, two in molars and two in premolars. Those in the premolars would be defined as relatively small restorations. When one also considers the amount of occlusal force premolars are subjected to, these amalgams could be replaced with direct composite resin restorations.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses