Basic Tissues

• To describe a cell and the function of its components

• To define the function of epithelium, name the various types and their locations

• To describe the origin of glands and the ways in which they may be classified

• To describe the components, functions, and location of general connective tissues

• To describe briefly the structure of bone and the two ways in which it is formed

• To describe briefly the components and origin of blood cells, their functions and normal numbers

• To discuss the three types of muscles and their functions, shapes and locations

CELL STRUCTURE

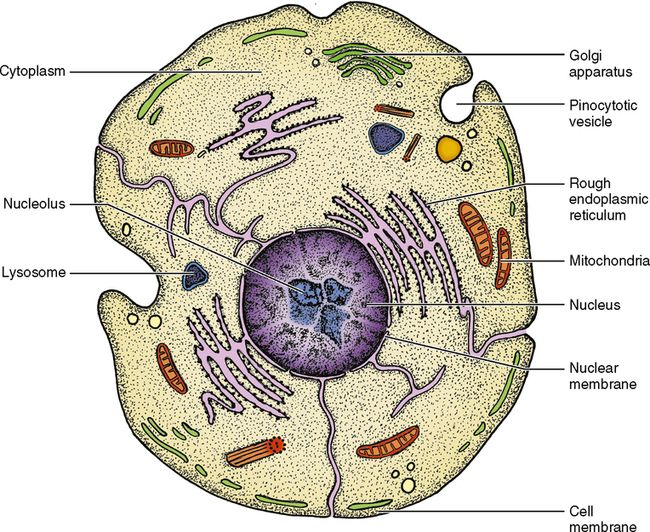

A cell can be thought of as a bag of fluid, generally varying in size from 0.01 to 0.05 mm in diameter. The wall of this bag is called the cell membrane, and its function is to keep the cellular fluid in and unnecessary foreign materials out. The cell membrane does have the potential to allow molecules of different sizes to pass through, and it can incorporate other membranes into it or add to it by itself. Fig. 17-1 shows the area inside the cell membrane, a fluid medium known as cytoplasm. Within the cytoplasm are other components of the cell, but looking through a light microscope you can probably distinguish only one structure—the nucleus. The nucleus is the master control of the cell. It contains deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), which control the operation of the cell. DNA is found in the chromosomes, which during nonmitotic times are found throughout the nucleus. Most of the RNA is found within the nucleolus. The nucleolus is a circumscribed dense area within the nucleus. There is generally one nucleolus per cell, but in some instances there may be more than one. The function of RNA is to carry genetic information or instructions from the DNA to the manufacturing parts of the cell.

Organelles

Small, usually oblong organelles known as mitochondria are responsible for energy production and for the rate at which the cell uses energy—commonly referred to as the metabolism of the cell. If the mitochondria are injured, the cell will not be able to function and may die. The number and location of the mitochondria are an indication of cellular activity and where the majority of activity is located within the cell. The mitochondria in Fig. 17-1 show the infoldings of the inner membrane of the mitochondria that form leaflike projections called cristae. The cristae have enzymes on their surface that aid in cell metabolism. Just as an increased number of mitochondria indicates increased cellular activity, an increase in cristae also indicates a more active cell.

Cellular Inclusions

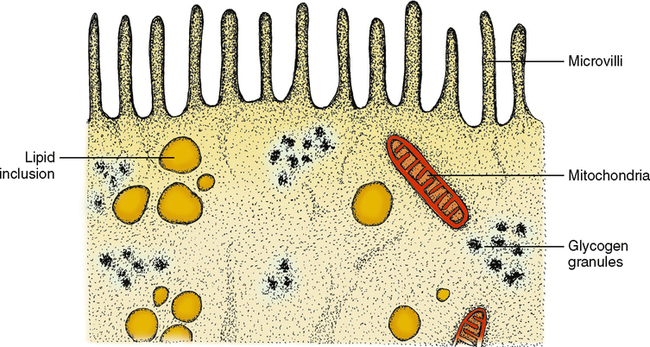

Organelles are intermixed in many cells with what are called cellular inclusions. This term indicates that the contents of the inclusions are not produced by the cell but rather are stored in the cell to be used at a later time and possibly another place. These inclusions may be little spheres of fat, known as lipid droplets, or multiple units of the sugar glucose, known as glycogen. Both lipid droplets and glycogen are storage forms of energy. When the body requires energy, they are released from the cell that stores them to travel to other parts of the body to be used as needed (Fig. 17-2). Many of these inclusions enter the cell by a process known as pinocytosis, which means a drinking in. The product pushes into the cell membrane from outside, and the membrane caves inward, finally pinching itself off and surrounding the inclusion without any loss of cytoplasm.

EPITHELIAL TISSUE

Simple Epithelium

Simple squamous epithelium

The word squamous means flat or platelike. If you looked at the surface of simple squamous epithelium, it would look like a collection of fried eggs side by side in a big pan. If you cut down through this epithelium and looked at a cross section, it would look like an overdone fried egg cut right through the yolk (Fig. 17-3). Looking at it from this side view you can imagine that such a thin layer would not be an extremely protective type of structure but might be thin enough for some materials to pass through between the cells. This type of epithelium is of the following two types:

1. Endothelial cells, found lining blood vessels; small, fluid-carrying tubes called lymphatic vessels; and lining the heart

2. Mesothelial cells, found lining cavities in the body such as pleural, peritoneal, and pericardial cavities

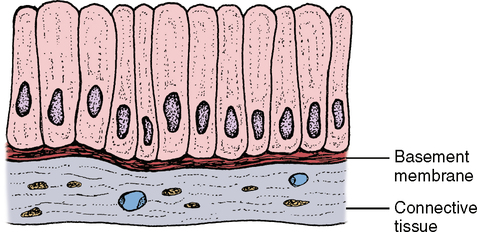

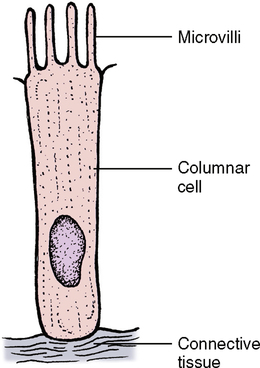

Simple columnar epithelium

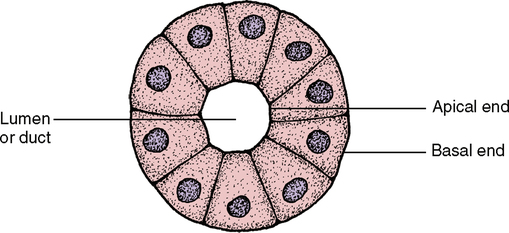

The columnar cells line the digestive tract from the stomach to the anal region (Fig. 17-4). In this location the main function of the epithelium is absorption of the breakdown products within the digestive tract. To do a more thorough job in this process, the end of the cell facing toward the lumen has small ultrastructural projections known as microvilli. These microvilli increase the surface area of the cell end by many times its original surface, thereby increasing the amount of nutrients that can be absorbed in the digestive tract (Fig. 17-5). The cells are also found in the ducts of various glands. When these columnar cells are packed together to form small ducts, they tend to form a pyramid shape (Fig. 17-6) and are often referred to as pyramidal cells. These cells also often have microvilli for the same purpose as cuboidal cells.

Pseudostratified columnar epithelium

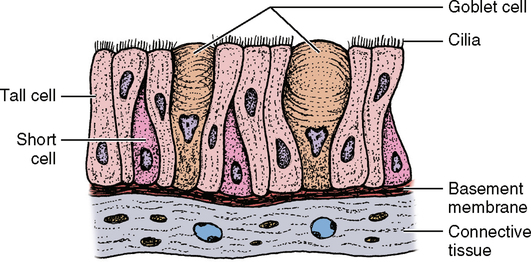

The term pseudostratified columnar epithelium means falsely layered epithelium or epithelium that looks like more than one layer. Some texts consider this a separate classification of epithelium from simple epithelium. Viewed under a microscope, it appears that several rows of nuclei are present, which would suggest more than one row of cells. However, on closer examination, it is evident that all of the cells reach down to the underlying tissue, the basement membrane. Some of the cells are very short, but others begin on the basement membrane with a very narrow stem and then expand once they reach the upper part of the cell layer. This type of epithelium is seen in several areas of the body, but the most prominent is the respiratory passages. In the respiratory tract and in other places, the epithelium has many small, single-celled glands called goblet cells intermixed with the epithelium (Fig. 17-7). These glands secrete a mucous substance and lubricate the surface of the epithelium for a number of functions. Along with the goblet cells, this epithelium also has small, hairlike projections known as cilia, which perform a waving, beating motion. These cilia are coated with mucus from the goblet cells and then trap contaminants in the air passing through the respiratory passages. These trapped particles are passed along from cilium to cilium by means of the beating motion until they reach the nasal opening or the opening of the oral cavity where they are removed from the body. Some simple columnar epithelia also have cilia. These cells are also found in male reproductive passages.

Stratified Epithelium

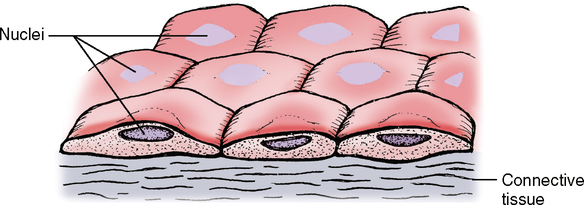

Transitional epithelium

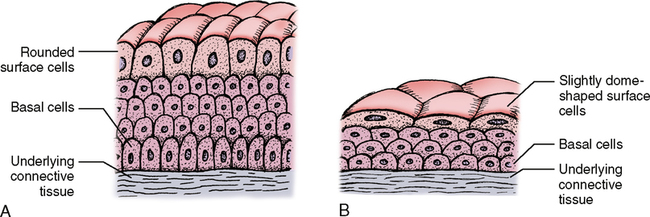

The term transitional indicates change, and that appropriately describes transitional epithelium. It changes in thickness and appearance as the need arises. Composed of multiple layers of cells and varying in thickness, it is found in the urinary system, with the primary concentration in the urinary bladder and ureter. When the bladder is empty, the epithelium is relaxed and about 8 to 10 layers of cells are present with the deepest layers composed of cuboidal cells and the surface layers slightly flattened but with rounded bulging nuclei (Fig. 17-8, A). When the bladder is full, the epithelium is stretched and may appear to be only 3 to 5 layers thick with the deepest cell layers somewhat flattened and the surface layers and the nuclei extremely flattened (Fig. 17-8, B). This change in appearance accounts for the name transitional and represents a very functional arrangement of cells.

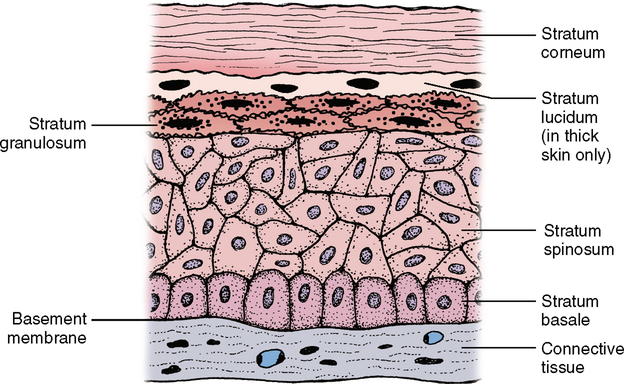

Stratum corneum

1. The cells may be alive and the epithelium referred to as nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. In this type, no stratum granulosum is present.

2. The cells on the surface, although still showing signs of nuclei, may be in the process of dying and are referred to as partly or parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Here, the stratum granulosum is very thin.

3. The cells on the surface may be dead and referred to as keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Here, the upper layer has no nuclei, and they appear somewhat opaque when they are not stained with dyes for microscopic study (Fig. 17-9; see also Fig. 23-1).

The thickness of this upper dead layer varies, depending on the amount of trauma or rubbing to which the tissue is subjected. As you know, working with a shovel or rake will eventually cause a callus to form, a result of a thickening of the stratum corneum and stratum spinosum. In thick skin such as the palms of the hands or the soles of the feet, a clear layer known as the stratum lucidum can be seen between the stratum granulosum and the stratum corneum. The cells are continually produced in the basal layer of the epithelium and move up through the other layers until they reach the surface where they are shed. This process can be seen when one sits in a tub of hot water for a while. Without using soap, a ring begins to develop around the tub. This ring is not readily visible but can be felt. The primary component of this ring is dead epithelial cells, which slough off and float to the edge of the tub. Just think of the mechanism that regulates the rate of cells produced with the rate of those lost and that adjusts to meet any changes. Without this control, we would either have skin as thick as an elephant or have no skin whatsoever (Table 17-1).

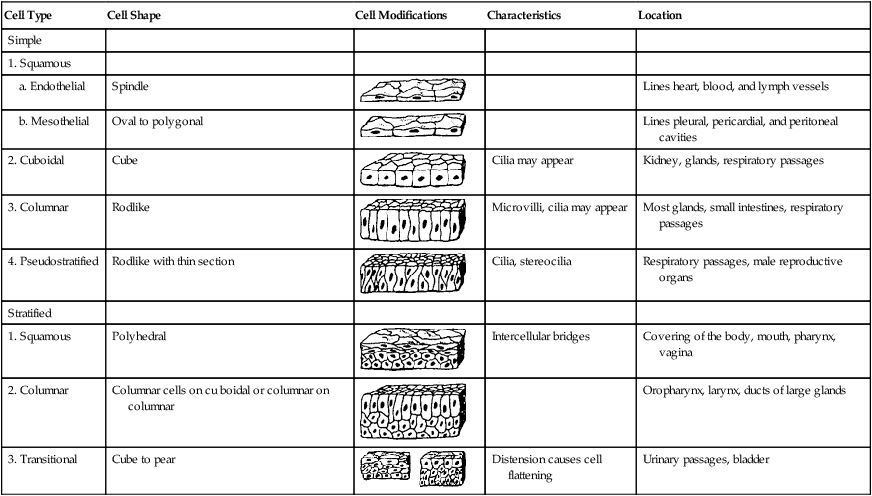

Table I7-I

| Cell Type | Cell Shape | Cell Modifications | Characteristics | Location |

| Simple | ||||

| 1. Squamous | ||||

| a. Endothelial | Spindle |  |

Lines heart, blood, and lymph vessels | |

| b. Mesothelial | Oval to polygonal |  |

Lines pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities | |

| 2. Cuboidal | Cube |  |

Cilia may appear | Kidney, glands, respiratory passages |

| 3. Columnar | Rodlike |  |

Microvilli, cilia may appear | Most glands, small intestines, respiratory passages |

| 4. Pseudostratified | Rodlike with thin section |  |

Cilia, stereocilia | Respiratory passages, male reproductive organs |

| Stratified | ||||

| 1. Squamous | Polyhedral |  |

Intercellular bridges | Covering of the body, mouth, pharynx, vagina |

| 2. Columnar | Columnar cells on cu boidal or columnar on columnar |  |

Oropharynx, larynx, ducts of large glands | |

| 3. Transitional | Cube to pear |  |

Distension causes cell flattening | Urinary passages, bladder |

From Avery JK: Essentials of oral histology and embryology, ed 2, St Louis, 2000, Mosby.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses