16 Introducing Lasers into the Dental Practice

Catone and Alling1 state that surgeons should possess at least a “fundamental understanding of qualitative laser physics and essential operation” of the lasers most useful in the clinical practice setting. Proper understanding of the science of lasers in dental practice is imperative in affording the clinician the knowledge and ability to deliver optimal treatment to patients. Many laser procedures are technique sensitive, and thus knowledge of the scientific basis of the treatment will enable the practitioner to improve and refine the techniques associated with the clinical practice and artistry of dentistry.

Cost of Acquiring a Laser

Cost is always one of the first considerations in the acquisition of a laser. The term “cost” can be viewed in several ways: “the amount or equivalent paid or charged for something: price; the outlay or expenditure (as of effort or sacrifice) made to achieve an object; [or] loss or penalty incurred esp. in gaining something.”2

Opportunity cost, also referred to as economic cost, is the cost of “passing up the next best choice” when making a decision. Opportunity cost is “the added cost of using resources (as for production or speculative investment) that is the difference between the actual value resulting from such use and that of an alternative (as another use of the same resources or an investment of equal risk but greater return).”2 Opportunity cost analysis is an important part of a company’s decision-making processes but is not treated as an actual cost in any financial statement.3 Opportunity cost is an important concept because it implies a choice between desirable but mutually exclusive results. Just as the acquisition of a laser has its cost, the choice not to purchase a laser also has associated costs. Among these opportunity costs are the loss of income that would have been produced by the new procedures that otherwise are referred out or not done at all, as well as the loss of referrals to the practice for those procedures that could be performed with a laser that were not previously done. Because there is a special perception of the “high-tech cutting edge” image that is projected by the use of lasers in the office, the loss of referrals is an additional opportunity cost lost to the practice resulting from the decision not to use lasers.

The first definition of cost mentioned is the price.2 The current price of a laser is about $4000 to $85,000 or more, depending on the type of laser and the manufacturer. The use of a laser can be paid for in four ways: purchase, finance, lease, and rent. The outright purchase of a laser may have distinct advantages if the cash flow of the practice or the assets of the owners allow for this option. Favorable tax laws may make the actual price significantly lower than the invoice price.

How do I adjust my fees for operative dentistry now that I am using a laser with a cost per “bur” (sapphire or quartz tip) of $10 to $85, rather than 99¢ for a carbide bur?

How do I adjust my fees for operative dentistry now that I am using a laser with a cost per “bur” (sapphire or quartz tip) of $10 to $85, rather than 99¢ for a carbide bur?Laser as Profit Center

Gingivectomy to improve access for operative dentistry, especially Class V lesions and root caries in geriatric patient

Gingivectomy to improve access for operative dentistry, especially Class V lesions and root caries in geriatric patientProcedures not previously done that enhance the results of routine procedures include the following:

Certain referred procedures now stay in the practice, as follows:

Oral medicine procedures, such as treatment of aphthous ulcers, herpetic gingivostomatitis, and lichen planus

Oral medicine procedures, such as treatment of aphthous ulcers, herpetic gingivostomatitis, and lichen planusReturn on Investment

Some of the items that should be included in this ROI would include profits from the following:

In this way a laser could be considered a profit center.

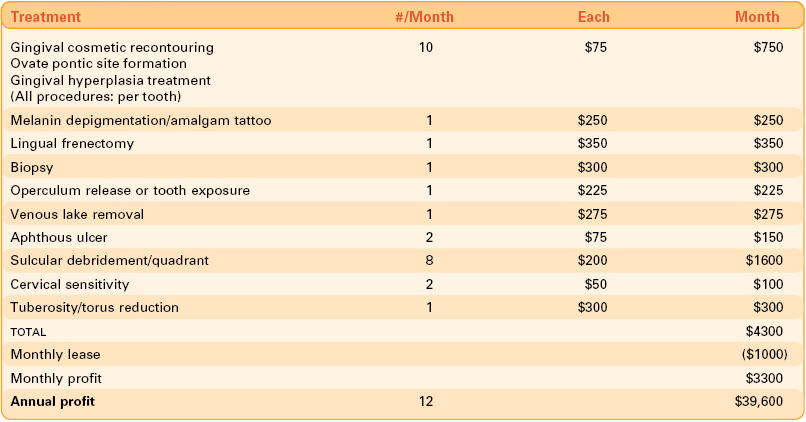

Table 16-1 demonstrates the significant positive financial impact a laser can have on the bottom line. It also illustrates possible income derived from the use of a laser for just a few procedures per month with very low fees (not using laser to full potential). If the laser’s price is $50,000, the income over this price in the first year is almost $40,000, so the laser would almost pay for itself in 1 year.

If you examine your practice for 1 week and track the number of procedures that could be performed with the laser, you can use Table 16-1 as a worksheet to evaluate the potential profit a laser can bring to your practice. Just plug in the number of procedures you tracked for the week, insert your fees, and do the calculations. Remember that this rough calculation does not include the amount of hours per week saved by using the laser for procedures that save time compared with conventional techniques (e.g., gingival retraction, implant recovery, gingivectomy), which will allow you to see more patients per week, thus generating even more income. This rough calculation also does not take into account the reduced time per week spent tending to postoperative visits for discomfort after surgical procedures, which are greatly reduced when lasers are used. Strauss4 emphasizes that “one of the main advantages of using the laser is the lack of postoperative problems and the minimal need for wound care.”

Tracking

Unique Selling Proposition

The USP is a marketing concept first proposed as a theory to explain a pattern among successful advertising campaigns of the early 1940s, making unique propositions to the customer that convinced them to switch brands. The USP is the “factor or consideration presented by a seller as the reason that one product or service is different from and better than that of the competition.”5 The USP of having a laser can be highlighted by emphasizing the following advantages of laser dentistry:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses