Biomechanical Aspects of a Modified Protraction Headgear

Ravindra Nanda

A routine dilemma in the treatment of children with developing Class III malocclusions is the choice of treatment strategy and whether early intervention will be successful in the long-term. Early treatment decisions should be based on several considerations, including genetics and family history; severity of the problem; whether the problem is diagnosed in the midface, mandible, or both; the age of the patient; patient compliance; and growth status of the patient.

The prevalence of children with Class III malocclusion in the United States is relatively small compared to Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Two studies evaluating the incisor relationship in children have reported an anterior crossbite incidence of 0.8% to 1.0%.1,2 One study reported a Class III molar relationship incidence of 3.8% in high school children.3 However, a Class III malocclusion in a child deserves special attention due to the esthetic, occlusion, function, and psychosocial concerns it raises.

Treatment of developing Class III patients is often based on the orthodontist’s expectations of treatment. The parents should be fully informed about the variability of results that can be expected. It is likely wishful thinking to aim to always convert a Class III growth pattern to a Class I growth pattern. The reality is that treatment results range from 100% success to no change at all in the long-term. The degree of success is based on the etiology of the Class III pattern, severity of malocclusion, age and growth status, choice of appliance used, and degree of patient cooperation. Other short-term goals should not be overlooked (i.e., to provide young Class III patients with a functioning occlusion, reduction in severity, and some esthetic improvement during their formative years).

Rationale for Using Protraction Headgear

Delaire et al.4–8 are credited with introducing the concept of protraction headgear to treat Class III malocclusions. Nanda introduced a modified protraction headgear in 1980,9 based on biomechanical concepts.

The rationale for protraction headgear is to apply heavy forces on the midface in order to advance the maxilla anteriorly. In patients with a normal sized mandible and retrusive maxilla, forward displacement of the maxilla is conceptually good. Several studies in the past 3 decades have shown that 25% to 41% of Class III problems in children are primarily the result of a retrognathic maxilla.10–12

The efficacy of protraction headgear is also supported by several studies in primates in the 1970s and 1980s.13–17 These studies, using cephalometrics and histological techniques, showed that treatment with an anterior force on the maxilla is capable of causing disassociation of sutural articulations by a resorption and apposition process at the sutural interfaces. Our own experience has also shown that the direction of midface protraction can be altered by changing the direction and point of delivery of the force.

In recent years noteworthy clinical studies have been reported regarding the use of protraction headgear.18–25 The majority of these studies show an anterior movement of the maxillary dentition, a significant extrusion of the upper molars, anterior displacement of the maxillary dentition, 1- to 3-mm anterior displacement of the maxilla, and a significant rotation of the mandible downward and backward.

A conventional protraction headgear, as described by Delaire et al.,4–8 and its variations use elastics from the molars (or other points at the occlusal plane level) to the facial mask. The interlabial gap and lips limit the ability to change the point of force application to attain predictable movement of the maxilla in the anterior direction.

Nanda9 introduced a modified protraction headgear in 1980, which allowed changes in the direction of force and point of force application on the maxilla as well as the chin. The study showed that use of a modified protraction headgear for 4 to 8 months can displace the maxilla 1- to 3-mm and maxillary dentition 1- to 4-mm. These changes were accompanied by remodeling at the B point, lingual tipping of the mandibular incisors, and downward rotation of the mandible. The cumulative effect of these changes was the correction of the Class III malocclusion. This chapter describes the biomechanical aspects of this headgear, which allows modification of forces in Class III patients to achieve the desired changes, such as in long face and short face Class III patients.

Components of Modified Protraction Headgear

There are two main components of a protraction headgear: intraoral setup and extraoral setup.

Intraoral Components

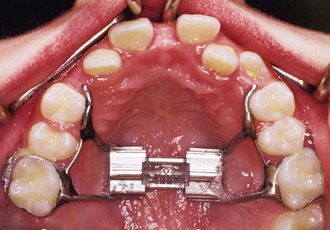

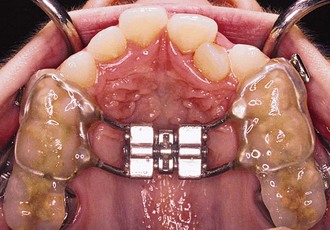

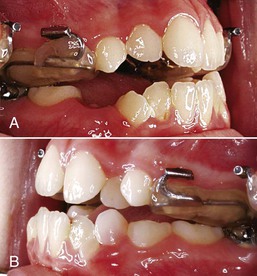

The protraction headgear force is applied via elastics to teeth or other devices supported by teeth and/or the palate. The primary aim is to transmit the force to the midface sutural interfaces. To achieve this, it is important to stabilize the maxilla as one unit (Fig. 16-1). In the primary dentition, it is advisable to use a cemented acrylic occlusal bite block or a removable acrylic plate with occlusal coverage (see Chapter 12). In patients with the mixed dentition and early permanent dentition, a removable acrylic plate (Fig. 16-2) should be used, supported by bands with headgear tubes on the molars or a rigid archwire with a palatal arch. Probably the best stabilization in patients with maxillary first molars is provided by a fixed rapid palatal expansion (RPE) device (Fig. 16-3). We prefer a Hyrax type of nonbonded device, as bonded RPEs (Fig. 16-4) interfere with the primary exfoliating teeth or teeth in the eruptive phase. Studies have also indicated that a simultaneous sutural expansion with an RPE at the start of protraction headgear treatment facilitates the anterior movement of the maxilla.19,20,26,27

Figure 16-1 A, Left and (B) right lateral views of an intraoral stabilization appliance. An acrylic bite block includes a heavy archwire to which a headgear tube is soldered. The bite block provides disocclusion to facilitate forward displacement of the maxilla and is cemented to posterior maxillary teeth.

Figure 16-2 Occlusal view of a removable intraoral stabilization appliance. The acrylic plate has a clasp that fits on a molar tube of a cemented band. This plate must be worn when the protraction appliance is in use.

Extraoral Components

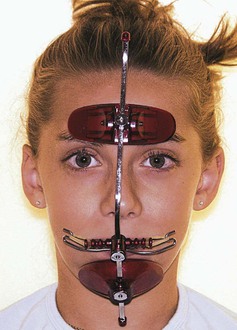

The extraoral components (Fig. 16-5) of a modified protraction headgear have two parts. The first is a facemask and the second is an intraoral-to-extraoral connecting force device that uses a modified headgear bow instead of intraoral elastics.

Figure 16-5 Complete modified protraction headgear device. It includes a facemask, a modified inner bow of a headgear, and elastics.

Commonly used facemasks have chin and forehead support connected by a heavy metal arch that has a horizontal bar for attachment of a force module. The forehead and chin supports are adjustable. The horizontal bar also must be adjustable vertically to vary the point of force attachment (Figs. 16-6 and 16-7).

Figure 16-6 Lateral view of a patient with the appliance shown in Figure 16-5 in place. The outer bow of the headgear is attached to the center bar of the facemask. The point of attachment on the mask can be moved up or down and the outer bow can be similarly positioned to achieve the desirable line of force.

A conventional headgear bow with a standard outer and inner bow without loops can be easily converted into a modified bow for use with the facemask. It is important that the molar band has a headgear tube. In cemented acrylic stabilization devices, a headgear tube can be embedded in acrylic.

To construct a reverse headgear bow (Fig. 16-8), a U-shaped horizontal bend is made in such a way that it can be inserted into the molar tubes from the distal side. Anteriorly, the bow should clear the incisors and should be between the upper and lower lips. The outer bow is modified to make a hook in the premolar area in such a way that elastics can be attached to the horizontal bar of />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses