16

A Winning Smile

Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder

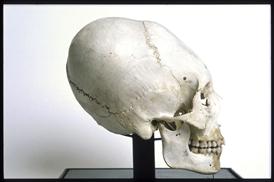

For thousands of years people have been altering the appearance of their skin by using makeup, tattooing or deliberate scarring. They have even modified the shape of the skeleton by binding the feet or skull during childhood (Figure 16.1). As the face has a major function in communication by conveying feelings and emotions, it is not surprising that teeth feature prominently in intentional bodily modification.

Figure 16.1 Egyptian skull whose shape has been altered by binding.

Source: Courtesy of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons.

The Smile

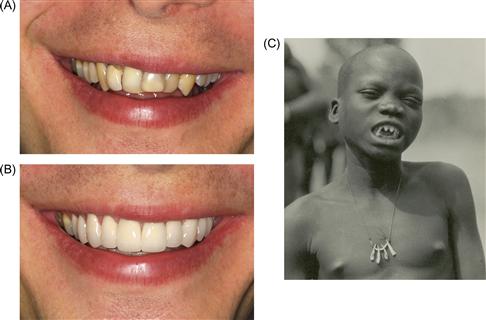

Which of the illustrations in Figure 16.2 do you find the most pleasing: A, B or C? Most people in Europe, Asia and America would probably choose Figure 16.2B. They would make Figure 16.2A their second choice as, compared with Figure 16.2B, the teeth are less regular and discoloured. Figure 16.2C would be a distant third. A person from certain parts of Africa might be unmoved by Figure 16.2A or B but swoon over the appearance of Figure 16.2C. Obviously, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and what appeals to one person does not hold for another.

Figure 16.2 Three smiles. Figures 2A and B are white European. Figure 2C is a Moro girl from Southern Sudan. Her upper four incisors have been filed into points while her lower incisors have been extracted and strung with beads as a neck ornament.

Source: (A and B) Courtesy of Dr C. Orr. (C) Courtesy of Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, accession number PRM 1998.353.23.2.

Through the widespread influence of the media, certain stereotypes have been promoted as icons of beauty. The public can be influenced to desire what they are told is the latest fashion. The appearance of the upper front teeth is particularly important as they are always on show. Having a ‘nice’ smile can boost one’s confidence and self-esteem and help in career and marriage prospects. Much work has gone into deciding what factors constitute a desirable smile in the Western world. The angulation of the teeth, their size, shape, colour and proportions, and how they contact (Figures 16.3 and 16.4) are all part of the equation. Straight, white teeth with no spacing and with a perfect symmetry are general objectives.

Figure 16.3 Ideal length (red) and width:length ratio (white) for the maxillary central incisor, and width proportions for the teeth as seen from the front (yellow). Source: Courtesy of Dr C. Orr.

View of upper front teeth superimposed on which are desirable measurements for an ideal smile. For the right upper central incisor, ideal crown length is 11 mm and crown width is 9 mm, giving a width:crown ratio of 0.7–0.8. On the left side of the patient, the width proportions of the teeth are compared.

Source: Courtesy of Dr C. Orr.

Figure 16.4 Subtle variations in the alignments of the long axis of the crowns of the maxillary teeth to help produce a perfect smile.

Source: Courtesy of Dr C. Orr.

As few people naturally have what is considered a perfect smile, many opt to have modification of their front teeth for cosmetic rather than clinical reasons. A popular procedure is to have false crowns or veneers placed over their filed-down front teeth. Despite a certain amount of discomfort, these procedures are relatively pain free (if not cost free!). Referring back to Figure 16.2, Figure 16.2A and B represents the same patient before and after cosmetic treatment.

In children whose teeth are crowded and the front ones unlikely to produce an attractive smile, at about ages 10–12 it is possible to take corrective measures by means of orthodontic treatment. Teeth farther back are extracted to provide the necessary space to move and straighten those in front by a combination of springs and wires.

Some people choose to cap a front tooth with gold, such as Mike Tyson, the former world heavyweight boxing champion. One or two show business celebrities have had diamond inlays put in their front teeth. However, the ultimate example of this practise is a removable appliance known as a dental grille, made of gold and diamonds, that can be slipped over the front teeth whenever desired. Even as far back as the seventh century BC, female Etruscan skulls from Italy have been found with gold bands supporting false teeth. Dental modifications using precious metals were likely carried out to indicate the wealth and status of the owner and to enhance their attractiveness.

Cultural Significance

Over the last few thousand years and up to recent times, the inhabitants of Africa, North, Central (especially Mexico, Costa Rica, Honduras) and Southern America, South East Asia and Japan have incorporated dental modifications as an important part of their culture. Deliberately altering the appearance of normal healthy teeth is limited to the front teeth, especially the upper central incisors. This can take many forms, but the design may be so specific as to indicate the place of origin.

There are many reasons for the practise of dental modification. It may allow a cultural group a feeling of common identity and recognition; reflect the status of an individual, particularly where the techniques are lengthy and costly; be undertaken for religious reasons (as it can be identified in artefacts representing deities); be related to magic/superstition or with warding off disease; be associated with coming-of-age or marriage rituals; be used as a type of branding to help identify criminals; and help with the pronunciation of a language.

Young adults, both male and female, starting at around age 15–20, are the main subjects for dental modification. Modifying or reshaping the crown of a permanent tooth requires the removal both of enamel and dentine. Due to the absence of efficient rotary drills and suitable tools/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses