Chapter 15

Tumours of the Mouth and the Management of Oral Cancer

- Oral precancer

- Oral cancer

- Aetiology and risk factors

- Clinical presentation

- Spread of oral cancer

- Principles of management

- Surgery

- Radiotherapy

- Chemotherapy

- Recent advances

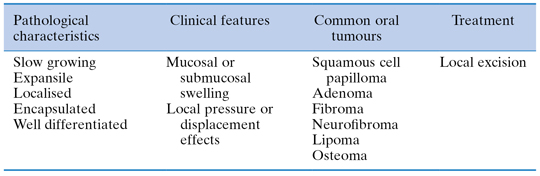

A tumour is a swelling or mass caused by excessive, continued growth of cells within a tissue; growth is unco-ordinated with that of normal tissue and persists in the same excessive manner after cessation of the stimulus that evoked it, in distinction to developmental abnormalities such as haemangiomas which are termed hamartomas. Tumours may be either benign or malignant (Table 15.1).

Table 15.1 Benign tumours of the mouth

Oncology is the study and science of new growths, while a neoplasm refers to any new, diseased form of tissue growth. Cancer is the overall name applied to malignant growths, more than 90% of which are derived from epithelial tissues, and is essentially a genetic disease caused by somatic mutation. The multistage theory of carcinogenesis believes that individual cancers arise from several sequential mutations in cellular DNA. There is a close correlation between cancer incidence and increased age, reflecting the time required to accumulate the critical number of genetic abnormalities needed for malignant change.

The two most significant characteristics of malignant growths are: local invasion, in which malignant cells either singularly or as cords or sheets infiltrate and destroy adjacent normal tissue, and metastasis, in which secondary tumours, by dissemination of tumour emboli through lymphatic and vascular channels, are formed at sites discontinuous from the primary. Death from cancer usually results from tumour deposition within vital organs such as the liver, lungs or brain, from a generalised carcinomatosis, or from uncontrolled disease at the primary site causing airway obstruction or haemorrhage from large blood vessels.

Oral Precancer

Fundamental to reducing cancer morbidity and mortality is the ability to recognise the earliest possible neoplastic changes in oral tissues. Dental practitioners have a unique opportunity during routine oral examination to detect malignant neoplasms while they are asymptomatic and often precancerous. In 1978 the World Health Organization (WHO) divided oral precancer into: precancerous lesions, altered tissues in which oral cancer is more likely to occur, and precancerous conditions, which are generalised states associated with a significantly increased risk of cancer (Table 15.2).

Table 15.2 Oral precancer

| Classification | Definition (WHO 1978) |

Clinical examples |

| Precancerous lesions | Morphologically altered tissue in which cancer is more likely to occur than in its apparently normal counterpart | Leukoplakia Erythroplakia Speckled leukoplakia |

| Precancerous conditions | Generalised states associated with a significantly increased risk of cancer | Immunosuppression Submucous fibrosis Sideropaenic dysphagia Discoid lupus erythematosus Actinic keratosis Lichen planus Syphilis |

While this remains a useful distinction, WHO terminology changed in 2005 to combine lesions and conditions into a unified category of potentially malignant disorders. This reflects the clinical reality that patients often present with widespread mucosal disease rather than isolated single lesions.

Epithelial dysplasia is defined as a collection of epithelial changes seen by light microscopy (primarily disordered tissue maturation and disturbed cellular proliferation) and is the most important determinant of the risk of malignant transformation of precancerous lesions. Pathologists qualitatively divide dysplasia into mild, moderate, severe or carcinoma-in-situ, depending on the extent of dysplastic features and the resultant risk of malignant change.

Epithelial dysplasia does not mean that a lesion will inevitably proceed to an invasive cancer, but an increased risk exists which worsens as the epithelium becomes increasingly dysplastic. Erythroplakic lesions generally contain more severely dysplastic epithelium than leukoplakia, and carry a higher risk of malignant change, as do speckled (red and white) lesions, while rough or nodular leukoplakias carry more risk than smooth (homogeneous) leukoplakias. Lesions arising in the floor of mouth and ventral tongue display higher rates of malignant transformation than other oral sites.

Box 15.1 outlines a pragmatic management protocol for patients with oral precancer. Laser surgery, a technique involving high-temperature tissue vaporisation and coagulative necrosis, allows accurate dissection and excision of premalignant lesions with reduced morbidity; minimal blood loss, reduction in postoperative pain, reduced scarring and rapid healing without skin grafting facilitate an acceptable strategy in patients for whom multiple or recurrent oral lesions are not uncommon.

Box 15.1 Management protocol for oral precancer

1 Eliminate risk factors – tobacco, alcohol

2 Clinical photographic record

3 Baseline haematology – full blood count, serum ferritin, B12, folate

4 Candidal swab

5 Incisional biopsy and dysplasia characterisation

6 Careful clinical follow-up and consider repeat biopsy for mild dysplasias

7 Laser excision for moderate/severe dysplasias

8 Long-term clinical follow-up

9 Monitor oral mucosa for field change

Field Change

An important complicating factor is that following surgical removal of individual precancerous lesions the rest of the patient’s upper aerodigestive tract mucosa may display widespread precancerous change, rendering patients susceptible to other primary cancers of larynx, oesophagus and lungs.

Oral Cancer

While the term oral cancer encompasses a range of malignant tumours arising within the lip, oral cavity and oropharynx (Table 15.3), more than 90% of oral cancers are primary squamous cell carcinomas arising from the oral mucous membrane.

Table 15.3 Malignancies of the oral cavity

| Primary tumours | Secondary tumours (metastases) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma (>90%) Minor salivary gland carcinomas Lymphoma Malignant melanoma Sarcoma |

Adenocarcinomas primarily from breast, renal and gastrointestinal tract primaries |

Worldwide, the incidence of oral cancer varies, with India and parts of Asia having the highest rates (40% of all cancers), while in Western countries the incidence is about 3% of all new cancers. However, this incidence is rising, particularly in younger patients and women, and oral cancer is a particularly lethal disease. Approximately 3400 new cases of oral cancer occur each year in the UK and there are about 1600 deaths.

Overall, the 5-year survival rate for patients with oral cancer is only 50%, although small, slow-growing lesions, tumours detected early and those presenting at the front of the mouth tend to do better. Posteriorly sited, rapidly growing tumours invading bone and with demonstrable lymph node metastases at presentation have the worst prognosis.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

The principal aetiological factors involve the use of tobacco and alcohol, which are known mucosal irritants and mutagenic agents. There is an important synergistic relationship between the two, which significantly increases the risk of cancer for those who both smoke and drink.

Patients who have had oral cancer previously, or those who have had lung, throat or oesophageal tumours, are also at high risk of developing new oral tumours or recurrence of their original cancers. Immunocompromised patients, such as those with AIDS or post-transplant patients on long-term immunosuppressive agents, are also at risk. Other postulated aetiological agents include viruses, chronic candidal infections, anaemias, nutritional and vitamin deficiencies, and for lip cancer, exposure to ultra-violet radiation.

Clinical Presentation

The most frequent clinical presentation is an indurated area of ulceration, often surrounded by leukoplakic or erythroplakic patches, while the commonest sites involved are the floor of the mouth, ventrolateral tongue and the soft palate complex (soft palate, retromolar trigone and anterior tonsillar pillar).

Oral cancer is usually asymptomatic in the early stages. Late presentation is common, although patients report non-specific symptoms over several months prior to their seeking attention. (Table 15.4 summarises the salient signs and symptoms suspicious of oral malignancy.)

Table 15.4 Clinical presentation of oral cancers

| Early lesions symptoms | Late lesions symptoms | Signs |

| Asymptomatic Irritation Discomfort |

Pain and swelling Paraesthesia Dysarthia Dysphagia |

Non-healing ulcer Induration and fixation of tissues Exophytic growth White/red mucosal patches Unexplained localised tooth mobility Non-healing tooth socket |

Spread of Oral Cancer

The most significant behavioural feature of oral cancers is their ability to invade and destroy local structures and to spread via lymphatics into the neck (Table 15.5). An appreciation of the pattern of spread is essential for effective treatment in order to control the disease within the mouth and neck.

Table 15.5 Spread of oral cancer

| (1) Local invasion | (2) Regional lymph node metastasis | (3) Distant spread |

| Soft tissues and muscles Perineural spaces Blood vessels Bone |

Lungs Liver Bones |

Local Invasion

Cancers can infiltrate widely into adjacent connective tissue, within muscle bundles, perineural spaces or local blood vessels. Direct extension via periodontal membrane or cortical deficiencies in edentulous ridges allows invasion of alveolar bone.

Lymph Node Metastasis

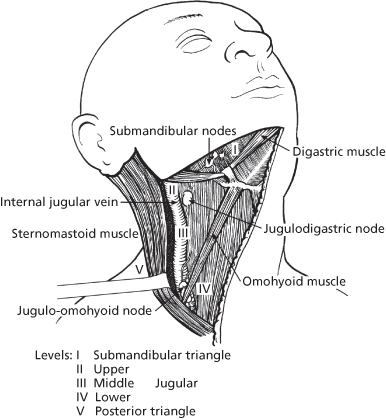

The likelihood of lymphatic spread increases with the size of the primary tumour. While the precise group of cervical lymph nodes affected depends on the location of the primary, intraoral cancers tend to spread initially to ipsilateral submandibular, upper, middle and lower deep cervical nodes (Levels I to IV in Figure 15.1). Tumours of the tongue, lip and floor of mouth close to the midline can metastasise to nodes on both sides of the neck, while the posterior triangle (Level V in Figure 15.1) may be involved in aggressive tongue and posterior oral tumours. The more lymph nodes involved, the presence of metastases in lower cervical nodes and the extension of tumour beyond the node capsule (extracapsular spread) all herald a worse prognosis.

Figure 15.1 Surgical anatomy of cervical lymph node groups. Levels: I, submandibular triangle; II, upper; III, middle jugular; IV, lower; V, posterior triangle.

Distant Spread

Distant spread tends to be more frequent in the later stages of the disease and may not be clinically apparent, although metastatic deposits have been found in the lungs, liver and bones in approximately 50% of post-mortem examinations carried out in patients dying with oral cancer.

Principles of Management

The management of patients with oral cancer presents considerable challenges and it is mandatory that an experienced and specialised multidisciplinary head and neck oncology team is involved in all stages of assessment, treatment and follow-up (Box 15.2). The overall aim of treatment is to eliminate the primary tumour and any neck node metastases, while minimising patient morbidity. The basic principles applied to the clinical management of oral cancer are listed in Box 15.3.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses