CHAPTER 15. Benign chronic white mucosal lesions

Chronic mucosal white plaques have sometimes been termed leukoplakias. This term literally means no more than a white plaque but, in the past, was widely but mistakenly regarded as implying premalignancy. However, only a small minority of white patches are premalignant (Ch. 16). The majority, without malignant potential, are discussed here (Table 15.1).

| Prevalence | Lesion | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Common |

Leukoedema

Frictional keratosis

Cheek biting

Fordyce’s granules

Stomatitis nicotina

Thrush

|

Normal variation

Friction

Cheek biting

Developmental

Pipe smoking

Candidal infection

|

| Uncommon |

Chemical

Hairy leukoplakia

White sponge naevus

Chronic mucocutaneous candidosis

Psoriasis

Oral keratosis of renal failure

Verruciform xanthoma

Skin grafts

|

Caustic chemicals

Epstein–Barr virus

Genetic

Candidal infection/immunodeficiency

Uncertain

Uncertain

Uncertain

Iatrogenic

|

LEUKOEDEMA → Summary p. 278

Leukoedema is a bilateral, diffuse, translucent greyish thickening, particularly of the buccal mucosa. It is a variation of normal, present in 90% of blacks and variable numbers of whites.

Histologically, there is thickening of the epithelium with intracellular oedema of the spinous layer.

Treatment is unnecessary but reassurance may be required.

FRICTIONAL KERATOSIS AND CHEEK BITING → Summaries pp. 277, 278

White patches can be caused by prolonged mild abrasion of the mucous membrane by such irritants as a sharp tooth, cheek biting or dentures.

Clinical features

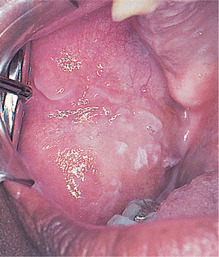

At first, the patches are pale and translucent (Fig. 15.1), but later become dense and white, sometimes with a rough surface. Habitual cheek biting causes an area of buccal mucosa to appear patchily red and white with a rough surface (Fig. 15.2).

|

| Fig. 15.1

Frictional keratosis. A poorly–defined patch of keratosis on the buccal mucosa is due to friction from the sharp buccal cusp of a grossly carious upper molar.

|

|

| Fig. 15.2

Cheek–biting. There is whitening of the buccal mucosa and a shredded surface.

|

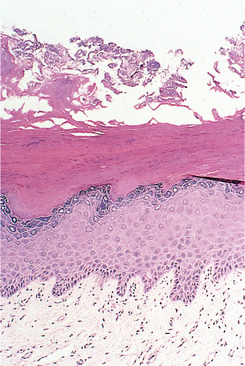

Pathology

The epithelium is moderately hyperplastic with a prominent granular cell layer and thick hyperkeratosis but no dysplasia (Fig. 15.3). There are often scattered chronic inflammatory cells in the corium.

|

| Fig. 15.3

Frictional keratosis. There is a slight hyperplasia of the basal cells and a thick layer of orthokeratin at the surface.

|

Management

Removal of the irritant causes the patch quickly to disappear. Biopsy is necessary only if the patch persists. Frictional keratosis is completely benign and there is no evidence that continued minor trauma alone has any carcinogenic potential.

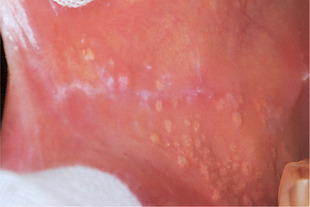

FORDYCE’S GRANULES → Summary p. 278

Sebaceous glands are present in the oral mucosa in at least 80% of adults, particularly the elderly. They grow in size with age and appear in the oral mucosa as soft, symmetrically distributed, creamy spots a few millimetres in diameter, particularly in older persons (Fig. 15.4). The buccal mucosa is the main site, but sometimes the lips and, rarely, even the tongue are involved.

|

| Fig. 15.4

Fordyce’s spots. Clusters of creamy, slightly elevated papules on the buccal mucosa.

|

These glands are sometimes mistaken for disease, but patients can be reassured that they are of no significance. If a biopsy is carried out, it shows a normal sebaceous gland with two or three lobules (Fig. 15.5).

|

| Fig. 15.5

Fordyce’s spots. Each spot is a histologically normal superficial sebaceous gland without a hair follicle.

|

PIPE SMOKER’S KERATOSIS (‘STOMATITIS NICOTINA’) → Summary p. 277

Smoker’s keratosis is seen among heavy, long-term pipe smokers and some cigar smokers.

Clinical features

The appearances are distinctive in that the palate is affected, but any part protected by a denture is spared. Changes are then seen only on the soft palate.

The lesion has two components – hyperkeratosis and inflammatory swelling of minor mucous glands. Either may predominate, but typically, white thickening of the palatal mucosa is associated with small umbilicated swellings with red centres (Fig. 15.6). The white plaque is sometimes distinctly tessellated (pavement-like).

|

| Fig. 15.6

Stomatitis nicotina (smoker’s palate). There is a generalised whitening with sparing of the gingival margin. The inflamed openings of the minor salivary glands form red spots on the white background.

|

Microscopy

The white areas show hyperorthokeratosis and acanthosis with a variable inflammatory infiltrate beneath. The diagnostic feature is the swollen, inflamed mucous glands with hyperkeratosis extending up to the duct orifice (Fig. 15.7).

|

| Fig. 15.7

Stomatitis nicotina (smoker’s palate). The epithelium is hyperplastic and hyperkeratotic, especially around the orifice of the duct where there is a concentration of inflammatory cells.

|

Management

The clinical appearances, history and ease of management are so distinctive that biopsy should not be necessary. If the patient can be persuaded to stop smoking the lesion resolves within weeks.

Key features are summarised Box 15.1.

Box 15.1

Pipe smoker’s keratosis (‘stomatitis nicotina’)

• Affects mucosa exposed to smoke (mainly the hard palate)

• Areas protected by denture unaffected

• Palate is white (keratotic) with umbilicated swellings with red centres (inflamed mucous glands)

• Responds rapidly to abstinence from pipe smoking

• Statistically, a raised risk of oral cancer but not in the hyperkeratinised (palatal) area (Ch. 16)

Epidemiological evidence suggests that pipe smoking raises the risk of cancer, but when oral cancer develops in association with pipe smoking, it typically appears not in the keratotic area on the palate (one of the least common sites for cancer) but low down in the mouth, often in the lingual retromolar region. This may be the result of carcinogens pooling and having their maximal effect in drainage areas of the mouth. It also suggests that there are different causes for the hyperkeratosis and any carcinomatous change.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses