14

Two Notorious People with Dental Connections

Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen (Convicted Wife Murderer) and John Henry (Doc) Holliday (Gambler and Gunman)

The dental profession can be proud of its achievements towards improving dental health. In this context, tooth decay has been greatly reduced, particularly with the discovery of the benefits of water fluoridation. This reduction in tooth decay has eliminated much of the extreme pain previously associated with dental abscesses. Similarly, gum disease can now be prevented with good oral hygiene, abolishing halitosis, bleeding gums and unnecessary loss of teeth. In the fields of orthodontics and cosmetic dentistry, the profession has pioneered advancements in improving facial aesthetics and thus restoring the self-confidence of large numbers of patients. An improved smile (see Chapter 16) can markedly increase job prospects (although exaggerated dental features have been the signature of certain show business personalities such as Terry Thomas and Ken Dodd) and marriage prospects.

Dental specialists have made significant contributions to our understanding of archaeology (see Chapter 7) and human evolution (see Chapter 13). Aspects of dental science have been important in apprehending criminals and murderers (forensic odontology). A particular example involved one of the most sensational mass murder trials of recent years when Fred West was arrested in 1994 and charged with the murder of 12 women, including his own daughter, Charmaine. Whilst in prison, he committed suicide, but not before claiming that his wife, Rose, had killed Charmaine. The police then charged Rose with her step-daughter Charmaine’s murder. The only way they could make this charge stick was to show that when Charmaine was murdered, Fred West was absent with a clear alibi.

The prosecution’s case ultimately depended on dental evidence. A picture of 8-year-old Charmaine was discovered in which she was smiling, with her teeth clearly visible and, at that age, still erupting. Fortuitously, the date when the picture was taken appeared on the negative. By comparing Charmaine’s skull and the slightly more advanced position of her teeth than was seen in the photograph, the forensic odontologist, Prof. David Whittaker, could estimate the time that had elapsed between when the photograph was taken and when she had been murdered. This provided a relatively firm date for the murder. It was known that during this particular period, Fred West was detained in prison serving a 6.5 month jail sentence for a vehicle offence. The jury convicted Rose West of murder.

Dentistry sometimes gets an undeservedly bad press, perhaps deriving from the old days of the barber-surgeons, who, apart from shaving you and giving you a haircut, might also do some simple surgical procedures ‘on the side’, such as blood-letting and tooth-pulling (all without anaesthetics, of course). Two of the most widely recognised people with dental connections are ‘Dr’ Crippen and ‘Doc’ Holliday, both, unfortunately, remembered not for the benefits they have brought to mankind but for their notoriety.

Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen (1862–1910)

Dr Crippen is known for his involvement in a sensational murder trial at the beginning of the twentieth century that made newspaper headlines around the world. The case had all the ingredients to appeal to the tabloid readership of today – murder, sex, a mutilated body and an international search for the culprit.

Dr Crippen was born in the United States, in the state of Michigan in 1862. He qualified as a homoeopath in Cleveland in 1885 hence his title Dr Crippen. He married in 1888, but his wife died in childbirth 4 years later. Crippen then married his second wife, Cora Turner, in 1892 and moved to London in 1897. He and his wife had little in common. She was outgoing, flirtatious and intent on pursuing a singing career in the Music Halls under the name of Belle Elmore, although having limited talent. She liked partying and became a popular hostess. She was the dominant figure in the marriage, bullying Crippen and embarrassing him in public. Crippen, on the other hand, was a mild-mannered, quiet, respectable-looking little man, bespeckled and with a full moustache (Figure 14.1), not fitting in with his wife’s circle of friends. It was his apparently benign personality which added spice to subsequent events.

Figure 14.1 Dr Crippen.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dr_crippen.jpg. This is a file from the Wikimedia Commons.

Crippen found employment mainly as a supplier of patent medicines, although also in the practise of ear, nose and throat disorders, plus some ophthalmology. In order to provide a source of extra income to satisfy his wife’s upwardly mobile aspirations, he went into business with a New Zealand dentist, Gilbert Rylance, forming The Yale Tooth Specialists in 1908. Their practice was based in Albion House, New Oxford Street, coincidentally sharing an office with Munyon’s Homoeopathic Remedies, his previous employers. In early 1910 he got more involved in dentistry by contributing another £200 to the business. It is unclear what his precise role was, but there is no record that he carried out any clinical work as a dentist. He presumably was a business partner who provided money to buy new equipment in return for a cut of the profits. However, when the events surfaced to which his name became attached, he was widely referred to in the press as a ‘dentist’.

Cora Crippen was last seen by her friends on 31 January 1910. When they enquired about her whereabouts, Crippen told them she had returned to America and showed them a letter, purportedly written by her, to this effect. However, the handwriting in the letter was clearly not Cora’s. Her friends began to worry and pressed Crippen for more information. A little later, he told them she had been taken seriously ill with double pneumonia and soon afterwards notified them of her death and subsequent cremation. Indeed, on 26 March 1910 a brief announcement of her death appeared in a stage magazine called The Era.

Although Cora led her own life, she and Crippen had agreed to remain together because of the stigma of divorce at the time. Immediately following Cora’s disappearance, Crippen was seen in the company of his young secretary, Ethel Le Neve, who was observed wearing some of his wife’s jewellery. Ethel had, in fact, been Crippen’s lover for 3 years. Cora’s friends, being suspicious of Crippen’s explanations and behaviour, eventually reported her disappearance to the police on June 30.

After carrying out some preliminary investigations, Chief Inspector Walter Drew interviewed Crippen at the offices of The Yale Tooth Specialists. During this interview, Crippen changed his story about Cora’s visit to America and her subsequent death. He stated that, following one of their many rows, she informed him she was leaving him for good and that he could make up any story he liked in order to cover her absence. Crippen assumed Belle was going back to America, probably to Chicago, to live with one of her old lovers, an ex-prize fighter named Bruce Miller. When she disappeared the next morning, Crippen said he had concocted the story about her death so as not to admit publicly that she had left him.

If Crippen had kept his nerve at this time and just continued with normal activity, his life could have turned out entirely differently. The onus would then have been on the police to search for his wife. With hundreds of similar missing persons in London alone, the search for someone in America would have been quietly dropped. Unfortunately for Crippen, this is not what transpired.

Crippen and Ethel were last seen in London on 9 July 1910. They fled to Antwerp where they boarded the steamer SS Montrose, travelling from London to Montreal on July 20. On board ship, Crippen posed as a clergyman, getting rid of his spectacles and moustache. Ethel was disguised as his son. Just before leaving, he still found time to write the following letter to his dental partner, Dr Rylance:

Dear Dr. Rylance,

I now find in order to escape trouble I shall be obliged to absent myself for a time. I believe the business as it is now going on you will run all right so far as money matters are concerned. If you want to give notice you should give six months’ notice in my name on September 25th, 1910. I shall write you later on more fully.

With kind wishes for your success,

Yours sincerely,

H. H. Crippen

On July 13, 4 days after Crippen fled London, police started to search his home for any evidence relating to his wife’s disappearance. On excavating the floor of the coal cellar, from which a very unpleasant odour soon arose, they uncovered the decaying remains of a butchered, human body. These consisted only of internal organs, some pieces of flesh covered by skin, patches of hair and fragments of clothing. No bones were recovered: the head, limbs and vertebral skeleton were all missing. There was no trace of the sex organs, so it was impossible to establish whether the remains were male or female. The circumstantial evidence overwhelmingly suggested that the remains were Crippen’s wife. A warrant was issued immediately for the arrest of Dr Crippen, and an international hunt began, with photographs of Crippen and Ethel Le Neve plastered over all the newspapers.

The appearance and suspicious behaviour of Crippen and Ethel, who were seen holding hands aboard ship, brought them to the attention of the captain of the SS Montrose, Henry George Kendall. Before leaving port, he had read in the newspapers about the search for Crippen. The SS Montrose was equipped with wireless telegraphy, recently invented by Marconi, and on July 22 Kendall instructed the following message to be relayed to his shipping manager:

Have strong suspicion that Crippen London Cellar Murderer and accomplice are amongst saloon passengers. Moustache shaved off, growing beard. Accomplice dressed as boy, voice, manner and build undoubtedly a girl.

This message was passed on to the police, who sent Chief Inspector Drew to intercept the SS Montrose, racing across the Atlantic aboard the liner SS Laurentic, that was scheduled to arrive in Canada ahead of the SS Montrose. As the news had been picked up by the press, the whole world avidly followed the chase in the newspapers, with the unsuspecting Crippen and Ethel totally unaware they had been located. Chief Inspector Drew boarded the SS Montrose as the ship entered the Gulf of St Laurence, off Quebec, and arrested the pair with the words ‘Good morning Dr Crippen’. The sensation this caused was partly due to the fact that it was the first time wireless telegraphy had been used to apprehend a criminal. The press were on hand to snap the two fugitives as they descended the gangplank of the SS Montrose with a police escort, and these images were flashed around the world.

Crippen and Ethel were returned to London to stand separate trials, with Crippen’s commencing on October 18. At his trial, Crippen was ill-served by both his solicitor, Arthur Newton, who was severely reprimanded for unprofessional conduct during the trial, and by the performance of his defence barrister Arthur Tobin. The prosecution was well served by the top barrister, Richard Muir

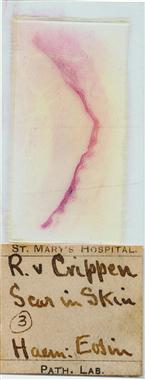

The trial saw the introduction of important advances in the use of forensic techniques in situations where most of the body was missing. The main prosecution witness was Dr (later Sir) Bernard Spilsbury, now regarded as the father of modern forensics. The evidence against Crippen was mainly circumstantial, as the only remains of his wife’s supposed body were some organs. The main evidence in trying to identify the body revolved around the remnants of skin. The prosecution witnesses argued that the skin came from the abdomen and that it revealed evidence of a scar. This seemingly matched with Cora Crippen’s previous medical history of an operation in the same area. Additional evidence in the prosecution case was the identification of traces of a poison (hyoscine) within the body, a compound that Crippen was known to have purchased recently. A pyjama top buried with the remains was said to match one that Crippen had bought.

The defence produced their own expert witnesses who denied that there was evidence of a scar and also that the skin could not definitely be identified as coming from the abdomen. In addition, they stated that the tests carried out by the prosecution witnesses did not prove the presence of hyoscine. Crippen claimed that he had used the hyoscine in very dilute doses for his patent medicines.

After a 5-day trial, Crippen was found guilty of his wife’s murder, the jury requiring less than 30 min to reach their unanimous decision. Protesting his innocence to the very end, Crippen was hanged on 23 November 1910, aged 48 years.

At Ethel Le Neve’s trial, which took place on 25 October, shortly after Crippen’s, she was defended by a brilliant barrister, Mr F.E. Smith. He decided not to put Ethel on the stand or provide any defence witnesses. His speech provided the only defence. He portrayed Ethel as a young innocent girl taken advantage of and led astray by an older and socially superior employer. His defence was that the prosecution could not prove beyond reasonable doubt that Ethel knew that Crippen murdered his wife. Ethel Le Neve was found not guilty. She disappeared from public view and died anonymously nearly 60 years later in 1967.

Since his death, many have doubted Crippen’s guilt. His mild personality did not seem to coincide with the cold and calculating character of a murderer. Many witnesses at the trial had said what a nice person he was. Having successfully disposed of the larger and most conspicuous parts of the body (skull, limbs, rib cage and vertebral column), why would he have felt the need to bury various soft tissue components, some wrapped up in his own clothing, close to his own dining room and capable of producing such an awful stench?

The most recent and compelling evidence to prove Dr Crippen’s innocence was published in 2010, using state-of-the-art forensic techniques of DNA analysis. Samples of the soft tissue remains of his ‘wife’ used by the prosecution as evidence to convict him were tracked down to the Royal London Hospital Archives and Museums. They existed on the original microscope slides prepared by Dr Spilsbury of what he believed was the abdominal skin from Cora Crippen (Figure 14.2). A team of scientists led by Prof. David Foran from the University of Michigan obtained permission to remove the soft tissue remains from one of the slides. The team carefully isolated and analysed DNA from the specimen and compared the results with three living members of Cora’s family. There was no match between the microscopical material and the family members, indicating that the tissue could not possibly have come from Cora Crippen. However, the most startling result was that the skin was from a man and not a woman. Assuming the validity of these results, it is clear that Crippen was found guilty on completely flawed evidence. Furthermore, two obvious questions arise from this study: What really happened to Cora Crippen? and Who was the man buried in Dr Crippen’s coal cellar? Based on this evidence, descendents of Crippen are engaged in trying to get a belated judicial pardon for him.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses