14

The dento-legal and ethical aspects of orthodontic treatment

INTRODUCTION

Orthodontics occupies a very interesting position within the dento-legal landscape, raising some issues that are peculiar to the specialty, and others that are particular manifestations of wider issues that apply throughout dentistry. At one extreme, it shares many of the medicolegal complications of treating children (in areas such as consent and the limitation of commencement of legal proceedings), while at the other extreme, it shares some of the risks that are associated with elective, cosmetic procedures carried out for adults.

This chapter will provide an overview of the dento-legal problems that arise in orthodontic treatment, highlighting areas of particular significance, and will then look a little more closely at some of the key issues.

FACTS AND MYTHS

It is a popular myth that orthodontics rarely results in complaints and litigation, and a further myth that orthodontic specialists encounter virtually no dento-legal problems. It is true that the majority of cases involving orthodontics arise from non-specialist practitioners who have not undergone any recognised formal training in the field, but also worth noting that specialists and non-specialists tend to have a different ‘mix’ of cases and issues arising within them.

While nowhere near the levels of endodontic treatment (responsible for 21–22% of all claims) and crown and bridgework (about 19%), orthodontics sits – perhaps surprisingly to those working in the field – at a level not unlike that of implant dentistry, each accounting for 5–7% of the total number of cases. But this needs to be placed in the context of how much of each of these types of treatment is being carried out, however interesting it might be as a ‘headline’.

A further myth is that any orthodontic cases that do arise will generally be low-value in terms of the cost of defending, settling or otherwise resolving the cases. In some jurisdictions, a third of all the highest value claims involve orthodontics in one way or another, and in one or two of them some of the highest value of all dental cases have involved orthodontics. It has featured in many regulatory (Dental Board/Dental Council) cases in many parts of the world, and in quite a few criminal cases (including allegations of fraud arising with claims for orthodontic treatment, fraudulent misrepresentation in terms of claims of special expertise on websites and practice literature, and claims of indecent assault).

WHAT GOES WRONG?

There is a difference between the technical/clinical deficiencies and failures in orthodontic treatment that would be apparent to experienced colleagues working in the same field, and the deficiencies and failures that are more visible to, and more easily understood by patients (or perhaps their parents). Because of this, problems of the latter variety are more likely to result in patient dissatisfaction and therefore have the potential to give rise to complaints and claims. Many studies in medicine and a few in dentistry have demonstrated that the drivers for litigation are much more likely to be human than technical. The work of Hickson et al.,1,2 Mangels,3 Beckman et al.4 and others5,6 have suggested that they have more to do with how the treatment is delivered and the relationship between patient and clinician, than with the technical/clinical quality of the treatment provided. Many of the most technically competent and skilled surgeons have the highest rate of litigation against them, and vice versa.

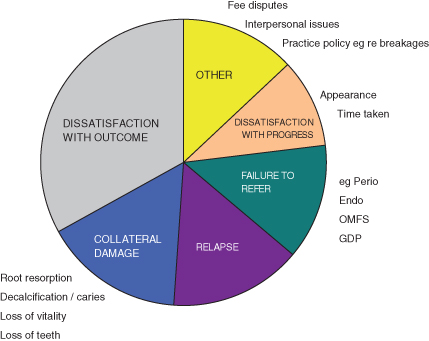

The more technical the specialty, the less likely it is that patients will be in a position to judge the technical aspects of the treatment and its outcomes. As a result, they will tend to judge the treatment by reference to other criteria and not least, by comparing what is being achieved, against what they had been led to expect (Figure 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Reasons for patient dissatisfaction. OMFS, oral and maxillofacial surgery; GDP, general dental practitioner.

WHEN (AT WHAT STAGE) DOES IT GO WRONG?

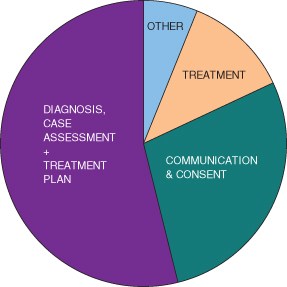

Here there is a marked difference between specialist and non-specialist providers of orthodontic treatment. As shown in Figure 14.2, the overwhelming majority of cases are primarily the result of deficiencies in the initial diagnosis, case assessment and treatment plan. This is where the additional knowledge and experience of the specialist pays dividends, and also where the non-specialist can sometimes run into problems which could be said to reflect an underestimation of the complexities of the case, and which treatment approach is most likely to result in the desired outcome.

Figure 14.2 Stages when patient management goes wrong.

Specialists have most of their problems in the area(s) of communication and consent – which includes communication with professional colleagues as well as with patients and (in the case of children) their parents. In many instances the problems from this source are compounded by incomplete or inadequate clinical records of the communication and/or consent process. Non-specialists are much more likely than specialists to create problems relating to the technical aspects of the treatment itself. Much of this relates to the management of expectations both in advance of treatment and as it proceeds, but a high level of specialist knowledge can and does bring its own problems in terms of the consent process. This is often seen where a specialist has a clear and uncompromising view as to what treatment approach should be provided, drawing perhaps from a detailed knowledge of the evidence base, and steers the patient strongly towards this treatment without explaining any alternative approaches or properly involving the patient in the decision-making process.

The evidence base is a crucially important tool in our clinical armamentarium, but it should never be used as a justification for denying a patient their right to autonomy and self-determination.

STANDARDS AND THE LAW

The quality of treatment is a subject that occupies orthodontists every bit as much as other clinicians, but as illustrated above, this can mean different things to different people – not least, the patients themselves. Many aspects of quality are the subject of standards that are specified by others. These can be summarised as:

- Legal standards (e.g. the requirements of national or local legislation)

- Civil standards (e.g. clinical negligence)

- Ethical/professional standards (as specified and enforced by regulatory bodies such as dental councils/boards)

- Voluntary standards (e.g. guidelines issued by bodies such as dental associations, colleges and organisations representing the specialty).

Some of the third parties involved in the above areas may intervene in the relationship between a dentist and a patient, even if the patient is delighted with the quality of care they have received.

The principle of negligence arises from the premise that everyone has a duty to act in a reasonable way in order to avoid causing harm, loss or injury to another party. This is often known as the duty of care and exists in one form or another in most countries around the world, even though the law operates differently from one country to another. In general, three requirements must be satisfied in order for negligence to be established:

- A duty of care must exist between the dentist and the injured party.

- The dentist must have failed in that duty, in one or more respects.

- The patient must have suffered damage, harm or loss as a direct result of a specific failure in the dentist’s duty of care (so-called ‘causation’).

The first of these is almost always very easy to satisfy since any dentist who accepts a patient for treatment will have an automatic duty of care to the patient.

The second requirement, i.e. the breach of the duty of care, can be more difficult to establish, and it immediately invites the question of professional standards, and of who decides whether a given treatment is sufficient to discharge the duty of care, or whether it falls below such a standard. In most countries, a dentist is not guilty of negligence if he or she has acted in accordance with a practice which is accepted as being proper by a responsible body of professional (peer) opinion. This remains the case even when it can be shown that there exists one or more other bodies of opinion that take a contrary view. It is sufficient to exercise the ordinary, reasonable skill of someone reasonably competent in your field – an expert level of skill is only necessary if you have professed to be an expert in your field.

These basic principles are sometimes referred to as the ‘Bolam test’, after a landmark UK case half a century ago,7 and have since been tested in the English courts at every level up to and including the House of Lords. Around the world, however, there is a progressive tendency to chip away at the edges of the Bolam principle. In Australia, for example, in the defining case of Rogers v. Whitaker (1992)8 the court took the view that it was not sufficient to apply the Bolam test to the question of consent in medical cases, even if there is a body of opinion that would not have given a certain warning to a patient prior to carrying out a medical procedure. The court was free to determine, despite this, whether or not the failure to give such a warning could amount to negligence on the part of the clinician. There is a growing view that the Bolam principle, now over 50 years old, is rather too paternalistic in approach for today’s more consumerist society. Rather than leaving it for other doctors and dentists, effectively, to decide what is or is not negligent, new test cases in many jurisdictions are progressively questioning and challenging the Bolam principle, especially in the area of consent.

It is well known that there are strongly held, but entirely divergent, />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses