14

14

Emergencies and Complications

Introduction

Problems will vary from the orthognathic to those of a more general nature, which can be life threatening. Although orthognathic surgery is usually carried out on young fit adults, life-threatening complications may arise. Careful technique, and expertise in the management of serious emergencies are essential. This includes the understanding the mysteries of medical monitoring.

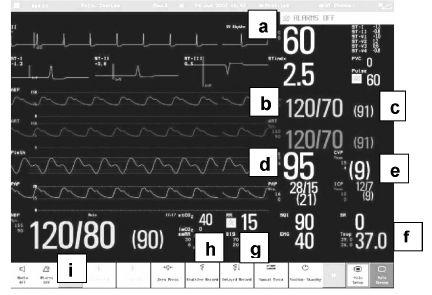

Medical Monitoring (Figure 14.1)

ECG: a basic knowledge of abnormal PQRST complexes and arrhythmias is essential for interpreting the ECG. “Three-lead” monitoring gives an interpretable rhythm-strip but is no replacement for a full “12- lead” ECG assessment when acute cardiac problems are suspected.

Heart rate (HR): derived from the ECG and the monitor can be set to detect bradycardia and tachycardia.

Arterial blood pressure (ABP): is measured by direct cannulation of the radial, brachial, dorsalis pedis or femoral arteries. The mean arterial pressure (MAP) is denoted in brackets. Non-invasive monitoring (NBP) is done with an appropriately-sized pneumatic cuff placed either around the upper arm or lower leg.

Central venous pressure (CVP): is useful as an indication of right ventricular preload. Serial readings (i.e. the trend of CVP measurements) are far more useful than single readings. The normal value is 2-6 mmHg. Respiration (RESP): is normally 14-20 a minute.

Figure 14.1 Intensive Care Monitor (by courtesy of Panasonic). (a) Heart rate. (b) Continuous invasive blood pressure (BP). (c) Current mean arterial pressure. (d) Oxygen saturation. (e) Central venous pressure. (f) Temperature. (g) Respiratory rate. (h) End tidal CO2. (i) Non-invasive cuff BP.

Oxygen saturation of arterial blood (SpO2): is usually measured by a digital pulse oximeter based on the light absorptive properties of oxygenated and deoxygenated Hb. Oxygen saturation monitoring, which assesses oxygenation, not ventilation, is no substitute for arterial blood gas assessment as there are both extrinsic and intrinsic reasons why the reading may be inaccurate.

Carbon dioxide: is expressed in a graphic form by the capnograph. Capnography is an indirect monitor that not only helps in the differential diagnosis of hypoxia, but also provides information about CO2 production, alveolar ventilation and respiratory patterns.

Temperature: can be monitored by mouth, axilla, tympanic membrane, oesophagus and rectum. Rectal and oesophageal measures are the most accurate.

Complications

1. Oedema and Infection

Oedema is reducible with pre-and postoperative dexamethasone and antibiotic cover as described earlier. Contrary to some popular practice vacuum drains can dramatically reduce the swelling arising from mandibular osteotomies, and the minivacuum drain is equally valuable for infraorbital haematomas following dissection through a subciliary incision. The same applies to the iliac crest donor site. Where possible leave drains for at least 24 hours after they cease to function.

Where there is gross postoperative swelling and pain, the presence of a haematoma is more likely than oedema alone. Treatment should be the release of the haematoma, especially if expanding, as it may be the presenting feature of a persistent arterial bleed, which needs to be identified and arrested.

There is some dispute as to whether clean operations require more than one pre-and postoperative antibiotic bolus. However prospective trials have shown that a five-day course produces less postoperative infection at the sagittal split site.

2. Bleeding Problems

a) Minor Haemorrhage

Even with previously healthy patients not receiving any medication which would predispose to excess bleeding, intraoperative blood loss is significantly reduced by the administration of an antifibrinolytic agent such as tranexamic acid 25 mg/kg orally or 0.5-1 g by slow intravenous injection pre-and postoperatively.

Tearing the periosteum on the medial aspect of the ascending ramus whilst exposing it for a sagittal split may produce a troublesome bleed, which can be controlled with a hot wet tonsil swab and pressure for 3 minutes. Damage to the facial vessels through the base of the subperiosteal pouch prepared for the mandibular buccal cortex cut responds to the same pressure and patience. Rarely the maxillary, tonsillar or lingual arteries may be damaged, giving rise to prolonged serous haemorrhage. Again, packing firstly with a swab, and secondly with a large piece of oxidised cellulose (Surgicel) should be sufficient, assisted by 0.5-1 g t.d.s. tranexamic acid (Cyclokapron, Kabi) given intravenously. If vigorous bleeding persists the external carotid may need to be tied off, as described below.

b) Persistent Haemorrhage

Failure to control bleeding despite efficient conservative measures may be due to the following.

i) A patent damaged artery, either the maxillary or tonsillar that require identification and ligation. Do not delay ligation of the external carotid if significant bleeding persists despite local ligation, packing and antifibrinolytic therapy for more than 30 minutes. This should allow time for investigation.

ii) A rare manifestation of a latent coagulation defect or defibrination. In both cases there is an evident lack of clot formation on the drapes and the wound oozes “watery blood”.

c) Management — General

Ensure early that adequate blood is available for replacement; if not, send venous samples for full blood count, cross-matching and a clotting screen which must include the thrombin time, prothrombin time (PT or INR), thromboplastin generation test, fibrin degradation products and a platelet count. In rare cases of acute defibrination there are prolonged prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APPT) and thrombin time (TT), increased fibrin degradation products and reduced platelets. The increased fibrin degradation products tend to have an anticoagulant effect.

Maintain the circulation with crystalloid solution until type specific or fully cross-matched blood is available. Remember the circulating blood volume in an average adult is around 5000 ml (75 ml/kg), and transfusion is required after a 20%-30% loss. In a child the circulating blood volume is equal to the weight in kilogrammes × 80 ml, and therefore a relatively small absolute volume will give a 20% loss.

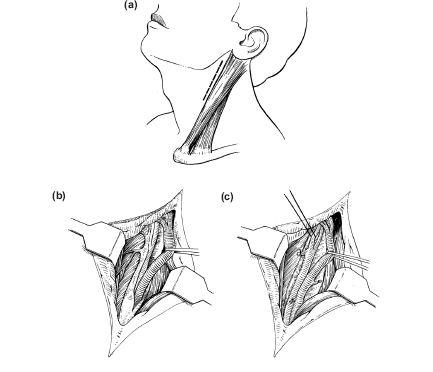

d) Ligation of the External Carotid Artery

Clean the neck with detergent and iodine. Resist the temptation to use an aesthetic skin crease incision, as this will limit access if the neck is distended with blood. Always incise obliquely along the anterior border of the sternomastoid muscle (Figure 14.2a). Remember the carotid bifurcation is just below the level of the hyoid bone. Therefore incise obliquely downwards from two fingers’ breadth below the angle of the mandible to the level of the prominence of the thyroid cartilage along a line drawn from the mastoid process to the sternal notch. Deepen the wound through fat, platysma and fascia using a No. 10 or 20 blade until the anterior border of sternomastoid muscle can be felt and seen.

The sternomastoid must be retracted firmly with a broad Langenbeck. The carotid triangle contains fine filamentous fascia, unless it has become infiltrated with oedema due to prolonged bleeding into the neck.

The carotid sheath fascia overlying the internal jugular vein is picked up with toothed forceps and incised along the vessel with McIndoe scissors. Anylon tape is passed around the internal jugular, once revealed, and attached to artery forceps; the vein is retracted distally with the sternomastoid muscle (Figure 14.2b).

Figure 14.2(a) Skin incision at upper anterior border of sternomastoid. (b) Opening of carotid sheath with retraction of internal jugular vein to reveal the carotid artery. (c) Ligation of external carotid artery.

The carotid will now be palpable and partially visible; again, fascia will need to be divided to expose the bifurcation. This may be obscured by one or more small veins, which must be tied with 3/0 polyglycollate or linen and divided. The external carotid is anteromedial to the internal carotid and can be identified by its branches. The superior thyroid artery often arises at the bifurcation and has to be ligated with a black silk or linen and divided to gain access to the main trunk. Ligatures are more easily passed around the vessel with small Adson’s artery forceps as they have a more pronounced right angle curve. Rather than search for a specific vessel it is better to tie the external carotid at its base. There is no need to divide it (Figure 14.2c).

A vacuum drain is inserted and sutured to the skin with 3/0 black silk and the wound closed in three layers using 3.0 polyglycollate for the platysma and subcutaneous layers and 5/0 interrupted Prolene sutures for the skin.

An absorbent non-adhesive dressing is then secured with adhesive tape.

e) Coagulation Defects

Persistent bleeding despite local and carotid ligation indicates either a factor deficiency (the most common unsuspected defect being von Willebrand’s disease) or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). By now the laboratory results should be available. A prolonged thromboplastin generation test suggests a missing clotting factor. The prothrombin time (INR) will not be of value unless this is an anticoagulant or advanced liver disease problem, which is unlikely in an osteotomy patient. If however, there are also raised fibrin degradation products and deficient platelets, DIC should be assumed to be the problem. Management should be as follows.

i) Maintain tissue perfusion and oxygenation with intravenous fluid support and supplemental oxygen.

ii) Fresh frozen plasma (FFP), which contains clotting factors as well as the natural anticoagulants antithrombin III and protein C, is given in doses of 15 ml/kg. Cryoprecipitate is given along with FFP to replace fibrinogen if levels are less than 80 mg/dl.

iii) Platelet transfusion, 1 unit/10 kg body weight, should be considered once platelet counts drops below 50,000/cu mm and also packed cells to replace erythrocytes.

iv) Antifibrinolytic agent (tranexamic acid 0.5-1 g IV) must be used to arrest the fibrinolytic process and conserve the clotting factors. However once this process has been recognised it is essential to consult a clinical haematologist for advice.

v) Any patient receiving a large volume of blood replacement (1-1.5 of the circulating volume within 24 hours) will require FFP, cryoprecipitate and platelets. At this stage a clinical haematologist should guide all blood product prescribing. Recombinant activated Factor VII is being increasingly trialled as a treatment for persistent bleeding but its use is currently restricted by the small evidence base and the high costs (£5000 for a single 4.5 mg vial).

vi) The patient has by now been infused with 5-10 litres of fluid, much of which will be distending the bladder. This will require an indwelling catheter (see below), not only to decompress the bladder but also to help calculate the state of fluid balance and renal perfusion.

vii) Continued bleeding into the tissues may fill the soft palate, the lateral wall of the pharynx and the neck, constituting a serious threat to the airway postoperatively. Blood will also have passed the throat pack into the larynx and almost certainly into the stomach. The airway can be managed by prolonged endotracheal intubation but this will be dependent on skilled postoperative intensive care. If support is not available, an early decision should be made to carry out a tracheostomy, which not only guarantees the airway but also prevents aspiration into the lungs of blood or gastric contents and allows aspiration of accumulated secretions from the bronchi.

viii) Remember to administer metoclopromide 10 mg and erythromycin 250 mg intravenously to promote gastric emptying of swallowed blood. Metoclopromide is a dopamine antagonist, which stimulates gastric emptying, and small intestinal transit whilst also enhancing the strength of oesophageal sphincter contraction. Erythromycin and related 14-member macrolide compounds act directly upon motilin receptors in gastrointestinal smooth muscle and, therefore acting as motilin receptor agonists, and also accelerate gastric emptying, increase the frequency of smooth muscle contractions, and shorten orocaecal transit time.

ix) Before the patient leaves the theatre a Ryles nasogastric tube should be passed to aspirate the blood and bile reflux from the stomach. Gastric acid reduction as a prophylaxis against aspiration may also be achieved by giving a proton pump inhibitor such as omeprazole 40 mg by slow intravenous injection. Under normal conditions the effects of proton pump inhibitors are enhanced if the drug is given the evening before surgery and again 2 hours prior to surgery commencing. However this is not possible in cases of surgical emergency.

f) Secondary Haemorrhage

The patient may suddenly bleed profusely postoperatively in the ward, or even at home. The common causes are a partially divided large vein or untied artery in the depths of a mandibular osteotomy wound. Occasionally an undetected coagulopathy such as von Willebrand’s is the underlying problem, especially when the bleeding is repeated.

The management must commence with pressure applied to the bleeding site with swabs, and rapid transfer to theatre for exploration and haemostasis, as described.

As with all severe haemorrhage up to 10 mg intravenous morphine should be given immediately by slow intravenous injection as a sedative analgesic, together with tranexamic acid 0.5-1 g intravenously to help conserve clotting factors and clot in favour of haemostasis.

g) Gastric Haemorrhage

The chance of stress-induced gastric erosion is small, even after prolonged orthognathic surgery. However, the combination of a patient with a history of peptic ulceration, a stressful surgical procedure, anti-inflammatory steroids and analgesics can produce a gastric bleed. Abdominal discomfort, tachycardia, true melaena and/or haematemesis and a fall in haemoglobin (a late sign) should alert one to this possibility. Initial treatment should include intravenous fluid support and administration of a proton-pump inhibitor (omeprazole), first as an intravenous bolus dose (40 mg), then as an intravenous infusion for 72 hours. Early endoscopy should be considered after consultation with a gastroenterologist so that the bleeding point can be injected or banded.

The aim of drug treatment is to raise gastric pH to above 4, thereby stabilising any clots that may have formed at the bleeding site. This is the reasoning behind the use of proton pump inhibitors over H2 receptor blockers such as ranitidine, which have a lesser effect on pH.

With vulnerable patients a regular prophylactic proton pump inhibitor, such as omeprazole or lansoprazole, should be administered as well as eliminating both steroids and non-steroidal antiinflammatory analgesic drugs from the intraoperative and postoperative regimen.

3) The Airway

After an uneventful operation, the airway should be maintained with a nasopharyngeal tube, which is sucked out throughout the postoperative 12-18 hours at 30-minute intervals. Unless the nurse ensures that the fine suction catheter passes beyond the end of the nasopharyngeal airway tube, the end will gradually become blocked with blood clot and will become an efficient airway obstruction (Figure 14.3a) the same can occur with a tracheostomy tube (Figure 14.3b). Some anaesthetists leave an endotracheal tube in situ which with modern closed suction units can be kept unobstructed with minimum effort and nursing intervention.

A facemask with 40% oxygen at a flow rate of approximately 5 litres/min ensures adequate tissue perfusion. In intensive care or high dependency units an intra-arterial line may have been inserted to monitor blood gases and invasive blood pressure is displayed on the cardiac monitor as a continuous arterial pressure trace. But this is not an alternative to the provi/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses