Regressive Alterations of the Teeth

Attrition, Abrasion and Erosion

Attrition

The first clinical manifestation of attrition may be the appearance of a small polished facet on a cusp tip or ridge or a slight flattening of an incisal edge. Because of the slight mobility of the teeth in their sockets, a manifestation of the resiliency of the periodontal ligament, similar facets occur at the contact points on the proximal surfaces of the teeth. As the person becomes older and the wear continues, there is gradual reduction in cusp height and consequent flattening of the occlusal inclined planes. According to Robinson and his associates, there is also shortening of the length of the dental arch due to reduction in the mesiodistal diameters of the teeth through proximal attrition.

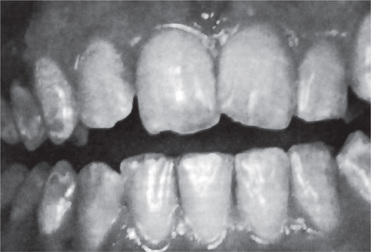

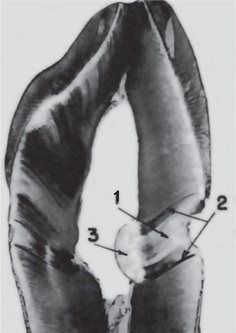

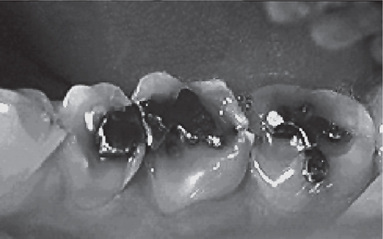

Advanced attrition, in which the enamel has been completely worn away in one or more areas, sometimes results in an extrinsic yellow or brown staining of the exposed dentin from food or tobacco (Figs. 13-1, 13-2). Provided there is no premature loss of the teeth, attrition may progress to the point of complete loss of cuspal interdigitation. In some cases the teeth may be worn down nearly to the gingiva, but this extreme degree is unusual even in elderly persons.

Figure 13-1 Advanced attrition.

This 14-year-old female exhibits total loss of surface characteristics and polished appearance of enamel on her maxillary incisors. The enamel layer was also very thin.

Abrasion

Robinson stated that the most common cause of abrasion of root surfaces is the use of an abrasive dentifrice. Although modern dentifrices are not sufficiently abrasive to damage intact enamel severely, they can cause remarkable wear of cementum and dentin if the toothbrush carrying the dentifrice is injudiciously used, particularly in a horizontal rather than vertical direction. In such cases abrasion caused by a dentifrice manifests itself usually as a V-shaped or wedge-shaped ditch on the root side of the cementoenamel junction in teeth with some gingival recession (Fig. 13-3). The angle formed in the depth of the lesion, as well as that at the enamel edge, is a rather sharp one, and the exposed dentin appears highly polished. It has been shown by Kitchin and by Ervin and Bucher that some degree of tooth root exposure is a common clinical finding, and a 66% incidence of abrasion among 1,252 patients examined was reported by Ervin and Bucher. The fact that abrasion was more common on the left side of the mouth in right-handed people, and vice versa, suggested that improper toothbrushing caused abrasion. The results of a study by the American Dental Association on the comparative abrasiveness of a number of popular dentifrices are shown in Table 13-1 and indicate the wide variation among the commercial products.

Tabel 13-1:

| Product | Manufacturer index | Abrasivity |

| T-Lak | Laboratories Cazé | 20 (20–21)+ (Lowest) |

| Thermodent | Chas. Pfizer & Co. | 24 (23–24) |

| Listerine | Warner-Lambert Pharm. Co. | 26 (22–30) |

| Pepsodent* | Lever Brothers Co. | 26 (23–29) |

| Amm-i-dent | Block Drug Co. | 33 (31–34) |

| Colgate with MFP | Colgate-Palmolive Co. | 51 (46–56) |

| Ultra-Brite | Colgate-Palmolive Co. | 64 (52–82) |

| Macleans,* Spearmint | Beecham Inc. | 66 (66) |

| Macleans,* regular | Beecham Inc. | 70 (68–72) |

| Pearl Drops | Cameo Chemicals | 72 (65–83) |

| Crest, mint* | Procter & Gamble Co. | 81 (71–90) |

| Close-up | Lever Brothers Co. | 87 (70–101) |

| Macleans, Spearmint | Beecham Inc. | 93 (85–99) |

| Macleans, regular | Beecham Inc. | 93 (74–103) |

| Crest, regular* | Procter & Gamble Co. | 95 (77–110) |

| Gleem | Procter & Gamble Co. | 106 (88–136) |

| Phillips | Sterling Drug Inc. | 114 (111–116) |

| Vote | Bristol-Myers Co. | 134 (112–162) |

| Sensodyne | Block Drug Co., Inc. | 157 (151–168) |

| Iodent No. 2 | Iodent Co. | 174 (172–176) |

| Smokers toothpaste | Walgreen Lab., Inc. | 202 (198–205) (Highest) |

Figure 13-3 Toothbrush abrasion.

Severe gingival notching of the teeth as a result of improper toothbrushing habits is clearly seen.

Other less common forms of abrasion may be related to habit or to the occupation of the patient. The habitual opening of bobby pins with the teeth may result in a notching of the incisal edge of one maxillary central incisor (Fig. 13-4). Similar notching may be noted in carpenters, shoemakers, or tailors who hold nails, tacks, or pins between their teeth. Habitual pipe smokers may develop notching of the teeth that conforms to the shape of the pipe stem (Fig. 13-5). The improper use of dental floss and toothpicks may produce lesions on the proximal exposed root surface, which also should be considered a form of abrasion.

Erosion

Dental erosion is defined as irreversible loss of dental hard tissue by a chemical process that does not involve bacteria. Dissolution of mineralized tooth structure occurs upon contact with acids that are introduced into the oral cavity from intrinsic (e.g. gastroesophageal reflux, vomiting) or extrinsic sources (e.g. acidic beverages, citrus fruits). This form of tooth surface loss is part of a larger picture of toothwear, which also consists of attrition, abrasion, and possibly, abfraction. Table 13-2 lists the definitions of each of these forms of tooth surface loss or tooth wear.

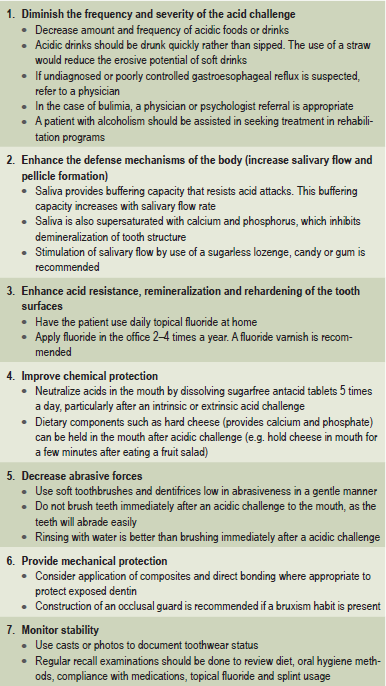

Table 13-2:

Definitions of tooth surface loss

Milosevic A. Toothwear: etiology and presentation. Dent Update 25: 6–11, 1998.

Causes

Intrinsic causes (acid source inside the body), for erosion are gastric acids regurgitated into the esophagus and mouth. Gastric acids, with pH levels that can be less than 1, reach the oral cavity and come in contact with the teeth in conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux and excessive vomiting related to eating disorders. The association of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) with dental erosion has been established in a number of studies in adults (Figs. 13-6, 13-7). GERD is a common condition, estimated to affect 7% of the adult population on a daily basis and 36% at least one time a month. In this condition gastric contents pass involuntarily into the esophagus and can escape up into the mouth. This is caused by increased abdominal pressure, inappropriate relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter or increased acid production by the stomach. However, GERD can also be ‘silent’ with the patient unaware of his or her condition until dental changes elicit assessment for the condition.

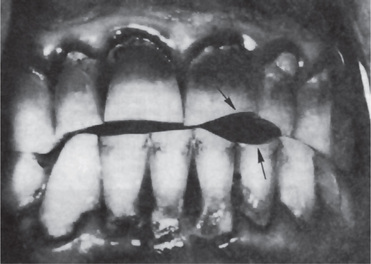

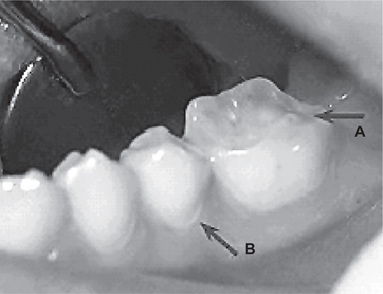

Figure 13-6 Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was discovered in this 19-year-old boy who exhibited early generalized erosion (arrow A).

Note the preservation of the enamel at the gingival crevice (arrow B).

Figure 13-7 This 33-year-old male with GERD had severe asymptomatic erosion.

Note the amalgams ‘rising’ above the adjacent eroded occlusal surfaces.

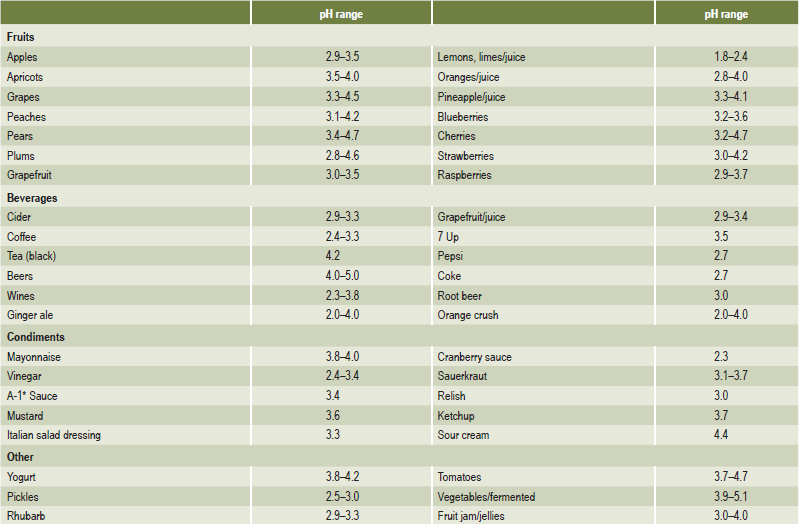

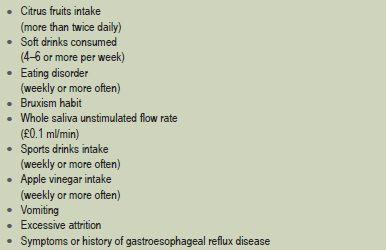

Chronic, excessive vomiting has long been recognized as causing erosion of the teeth. The patient with an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia is the classic example. The problem was first reported by Hellstrom and Hurst in 1977. Many reports and reviews have been published on the topic since that time. Although erosion caused by vomiting typically affects the palatal surfaces of the maxillary teeth, it is also common for individuals with eating disorders to consume large amounts of acidic beverages and fresh fruits (Tables 13-3, 13-4). This results in another source of acid exposure, primarily affecting the labial surfaces of the teeth. In addition, treatment for bulimia may include use of antidepressants or other psychoactive medications that may cause salivary hypofunction. Therefore, the cause of erosion cannot be reliably determined from its location.

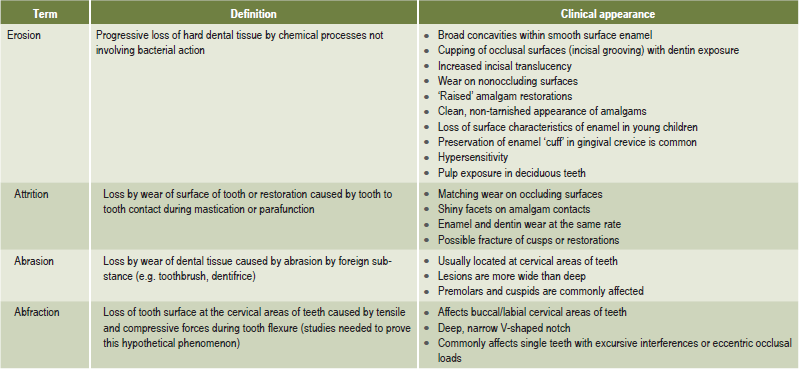

Management of Erosion

In some cases, an etiologic agent is not identifiable. In other cases, the etiologic agent may be difficult to control, such as the problem of alcoholism. However, regardless of the cause, it is important to follow preventive measures to prevent the progress of erosion. There are several preventive measures that can be taken to control tooth erosion. These are listed in Table 13-5. Patient education is of paramount importance. Much of erosion prevention depends on the compliance of the patient with dietary modification, use of topical fluorides, use of occlusal splint, etc.

Abfraction

Abfraction is currently described as a mode of tooth loss which has clinical and circumstantial evidence. Till recently this type of tooth loss which is mainly confined to the gingival third of the clinical crown was thought to be the result of toothbrush abrasion. It is proposed that with each bite, occlusal forces cause the teeth to flex though little. Constant flexing causes enamel to break from the crown, usually on the buccal surface. The physiological basis of this type of tooth substance loss held that, while not providing a complete explanation, does offer a significant clue to the real cause of this troubling phenomenon. Grippo, in 1991, coined the term abfraction to describe the pathologic loss of both enamel and dentin caused by biomechanical loading forces (Fig. 13-8). He stated that the forces could be static, such as those produced by swallowing and clenching; or cyclic, as in those generated during chewing action. The abfractive lesions were caused by flexure and ultimate material fatigue of susceptible teeth at locations away from the point of loading. The breakdown was dependent on the magnitude, duration, direction, frequency, and location of the forces.

Dentinal Sclerosis: (Transparent Dentin)

Sclerosis of primary dentin is a regressive alteration in tooth substance that is characterized by calcification of the dentinal tubules. It occurs not only as a result of injury to the dentin by caries or abrasion but also as a manifestation of the normal aging process. For many years it has been known that if a ground section of a tooth with a very shallow carious lesion of the dentin is examined by transmitted light, a translucent zone can be seen in the dentin underlying the cavity (Fig. 13-9). This was readily recognized as being due to a difference between the refractive indices of the sclerotic or calcified dentinal tubules and the adjacent normal tubules. Both Beust and Fish showed that dyes do not penetrate those dentinal tubules that are sclerotic as a result either of age or of a slowly progressive type of dental caries.

Dead Tracts

‘Dead tracts’ in dentin are seen in ground sections of teeth and are manifested as a black zone by transmitted light but as a white zone by reflected light (Fig. 13-9). This optical phenomenon is due to differences in the refractive indices of the affected tubules and normal tubules. The nature of the change in the affected tubules is not known, although these tubules are not calcified and are permeable to the penetration of dyes.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Attrition, Abrasion and Erosion

. Attrition, Abrasion and Erosion . Abfraction

. Abfraction . Dentinal Sclerosis

. Dentinal Sclerosis . Dead Tracts

. Dead Tracts . Secondary Dentin

. Secondary Dentin . Reticular Atrophy of Pulp

. Reticular Atrophy of Pulp . Pulp Calcification

. Pulp Calcification . Resorption of Teeth

. Resorption of Teeth . Hypercementosis

. Hypercementosis . Cementicles

. Cementicles