CHAPTER 13 Preparation of the Mouth for Removable Partial Dentures

Oral Surgical Preparation

Extractions

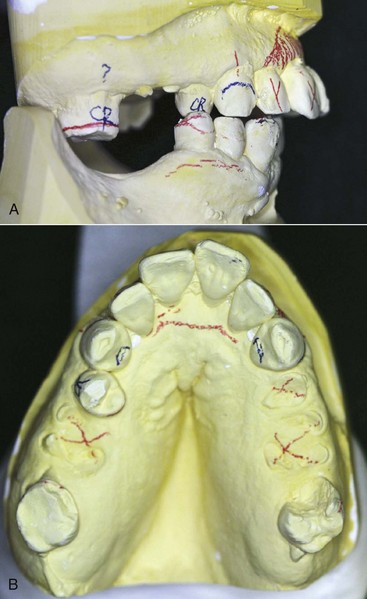

Planned extractions should occur early in the treatment regimen but not before a careful and thorough evaluation of each remaining tooth in the dental arch is completed (Figure 13-1). Regardless of its condition, each tooth must be evaluated in terms of its strategic importance and its potential contribution to the success of the removable partial denture. With the knowledge and technical capability available in dentistry today, almost any tooth may be salvaged if its retention is sufficiently important to warrant the procedures necessary. On the other hand, heroic attempts to salvage seriously involved teeth or those of doubtful prognosis for which retention would contribute little if anything, even if successfully treated and maintained, are contraindicated. Extraction of nonstrategic teeth that would present complications or those that may be detrimental to the design of the removable partial denture is a necessary part of the overall treatment plan.

Removal of Residual Roots

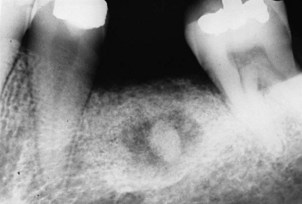

Generally, all retained roots or root fragments should be removed. This is particularly true if they are in close proximity to the tissue surface, or if associated pathologic findings are evident. Residual roots adjacent to the abutment teeth may contribute to the progression of periodontal pockets and compromise the results of subsequent periodontal therapy. Removal of root tips can be accomplished from the facial or palatal surfaces without resulting in a reduction of alveolar ridge height or endangering adjacent teeth (Figure 13-2).

Impacted Teeth

Alterations that affect the jaws can result in minute exposures of impacted teeth to the oral cavity via sinus tracts. Resultant infections can cause considerable bone destruction and serious illness for persons who are elderly and not physically able to tolerate the debilitation. Early elective removal of impactions prevents later serious acute and chronic infection with extensive bone loss. Any impacted teeth that can be reached with a periodontal probe must be removed to treat the periodontal pocket and prevent more extensive damage (Figure 13-3).

Malposed Teeth

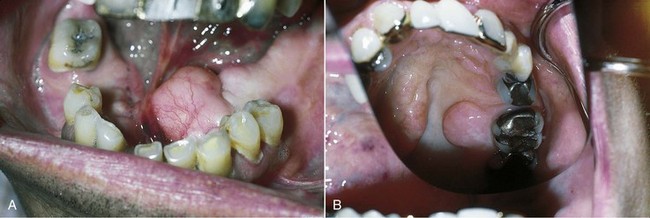

The loss of individual teeth or groups of teeth may lead to extrusion, drifting, or combinations of malpositioning of remaining teeth (Figure 13-4). In most instances, the alveolar bone supporting extruded teeth will be carried occlusally as the teeth continue to erupt. Orthodontics may be useful in correcting many occlusal discrepancies, but for some patients, such treatment may not be practical because of lack of teeth for anchorage of the orthodontic appliances or for other reasons. In such situations, individual teeth or groups of teeth and their supporting alveolar bone can be surgically repositioned. This type of surgery can be accomplished in an outpatient setting and should be given serious consideration before additional teeth are condemned or the design of removable partial dentures is compromised.

Exostoses and Tori

The existence of abnormal bony enlargements should not be allowed to compromise the design of the removable partial denture (Figure 13-5). Although modification of denture design can, at times, accommodate for exostoses, more frequently this results in additional stress to the supporting elements and compromised function. The removal of exostoses and tori is not a complex procedure, and the advantages to be realized from such removal are great in contrast to the deleterious effects that their continued presence can create. Ordinarily the mucosa covering bony protuberances is extremely thin and friable. Removable partial denture components in proximity to this type of tissue may cause irritation and chronic ulceration. Also, exostoses approximating gingival margins may complicate the maintenance of periodontal health and lead to the eventual loss of strategic abutment teeth.

Hyperplastic Tissue

Hyperplastic tissues are seen in the form of fibrous tuberosities, soft flabby ridges, folds of redundant tissue in the vestibule or floor of the mouth, and palatal papillomatosis (Figure 13-6). All these forms of excess tissue should be removed to provide a firm base for the denture. This removal will produce a more stable denture, will reduce stress and strain on the supporting teeth and tissues, and in many instances will provide a more favorable orientation of the occlusal plane and arch form for the arrangement of the artificial teeth. Appropriate surgical approaches should not reduce vestibular depth. Hyperplastic tissue can be removed with any preferred combination of scalpel, curette, electrosurgery, or laser. Some form of surgical stent should always be considered for these patients, so that the period of healing is more comfortable. An old removable partial denture properly modified can serve as a surgical stent. Although hyperplastic tissue has no great malignant propensity, all such excised tissue should be sent to an oral pathologist for microscopic study.

Osseointegrated Devices

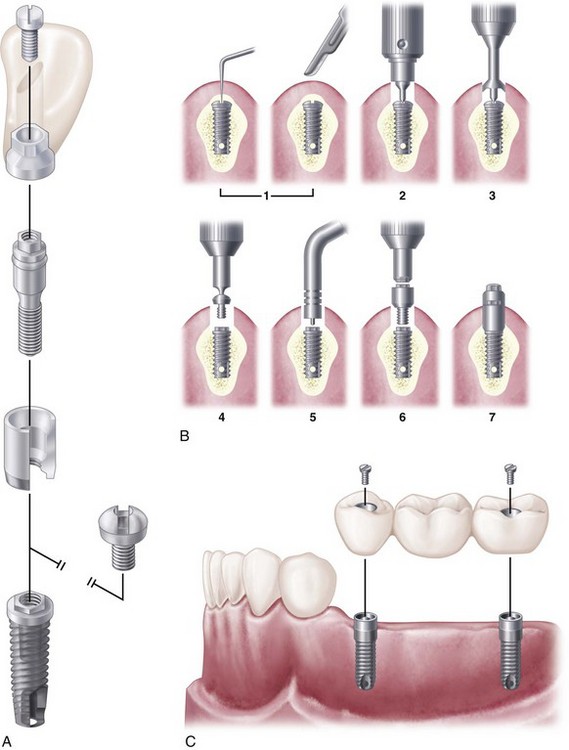

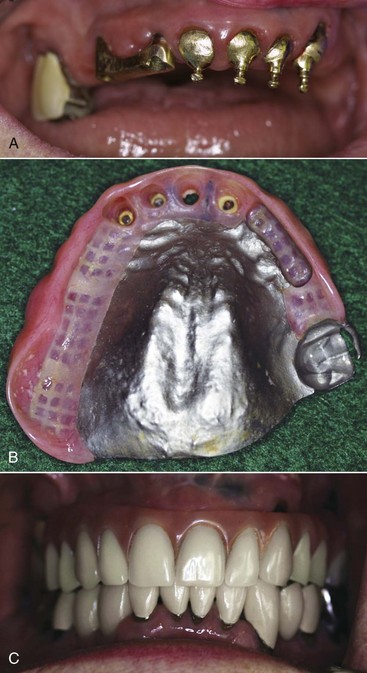

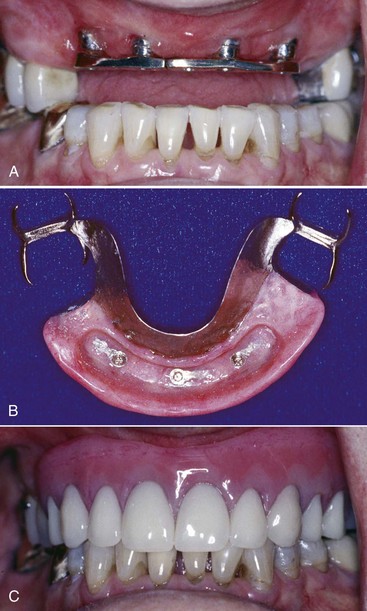

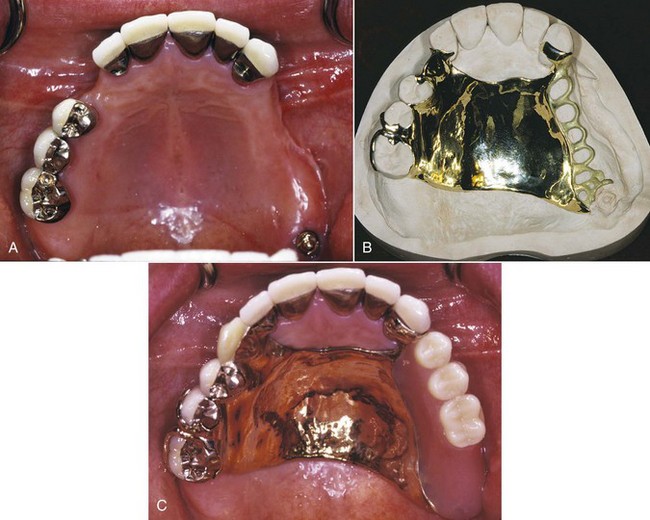

A number of implant devices to support the replacement of teeth have been introduced to the dental profession. These devices offer a significant stabilizing effect on dental prostheses through a rigid connection to living bone. The system that pioneered clinical prosthodontic applications with the use of commercially pure (CP) titanium endosseous implants is that of Brånemark and coworkers (Figure 13-7). This titanium implant was designed to provide a direct titanium-to-bone interface (osseointegrated), with basic laboratory and clinical results supporting the value of this procedure.

Implants are carefully placed using controlled surgical procedures and, in general, bone healing to the device is allowed to occur before a dental prosthesis is fabricated. Long-term clinical research has demonstrated good results for the treatment of complete and partially edentulous dental patients using dental implants. Although research on implant applications with removable partial dentures has been very limited, the inclusion of strategically placed implants can significantly control prosthesis movement (See Chapter 25, Figures 13-8 through 13-10).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses