Inflammatory Jaw Lesions

Pulpitis

Clinical and Histopathologic Features

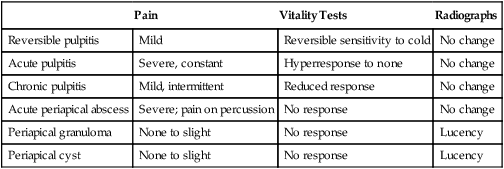

Several detailed classifications of pulpitis that are based on histopathologic changes have been proposed. Because of the difficulty in correlating clinical features with microscopy, these schemes have proved to be of little practical value. Instead, most practitioners prefer a simple classification that is helpful in the clinical setting relative to treatment and prognosis (Table 13-1).

TABLE 13-1

PULPITIS AND PERIAPICAL DISEASES

| Pain | Vitality Tests | Radiographs | |

| Reversible pulpitis | Mild | Reversible sensitivity to cold | No change |

| Acute pulpitis | Severe, constant | Hyperresponse to none | No change |

| Chronic pulpitis | Mild, intermittent | Reduced response | No change |

| Acute periapical abscess | Severe; pain on percussion | No response | No change |

| Periapical granuloma | None to slight | No response | Lucency |

| Periapical cyst | None to slight | No response | Lucency |

Treatment and Prognosis

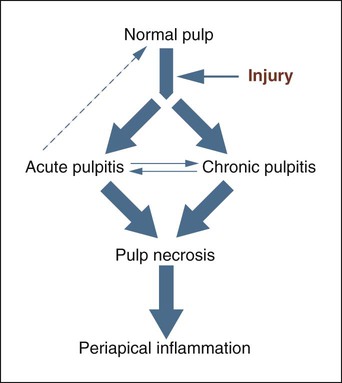

With chronic pulpitis, pulpal death is the characteristic end result (Figure 13-1). Removal of the cause may slow the process or occasionally may save the vitality of the pulp. Endodontic therapy or extraction is typically required. Chronic hyperplastic pulpitis is essentially an irreversible end stage that is treated with pulp extirpation and an endodontic filling or extraction.

Periapical Abscess

Etiology

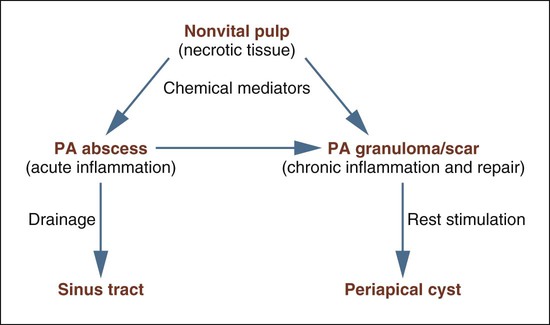

Numerous sequelae may follow untreated pulp necrosis and are dependent on the virulence of the microorganisms involved and the integrity of the patient’s overall defense mechanisms (Figure 13-2). From its origin in the pulp, the inflammatory process extends into the periapical tissues, where it may present as a granuloma or cyst (if chronic) or an abscess (if acute). Acute exacerbation of a chronic lesion may also be seen. Necrotic pulpal tissue debris, inflammatory cells, and bacteria, particularly anaerobes, all serve to stimulate and sustain the periapical inflammatory process.

Clinical Features

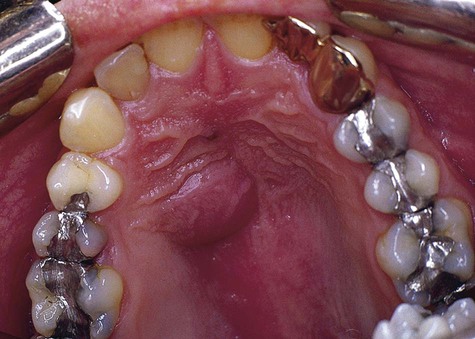

Patients with periapical abscesses typically have severe pain in the area of the nonvital tooth caused by pressure and the effects of inflammatory chemical mediators on nerve tissue. The exudate and neutrophilic infiltrate of an abscess put pressure on surrounding tissue, often resulting in slight extrusion of the tooth from its socket. Pus associated with a lesion, if not focally constrained, seeks the path of least resistance and spreads into contiguous structures (Figures 13-3 to 13-5). The affected area of the jaw may be tender to palpation, and the patient may be hypersensitive to tooth percussion. The involved tooth is unresponsive to electrical and thermal tests because of pulp necrosis.

Because of the rapidity with which this lesion develops, time is generally insufficient for significant amounts of bone resorption to occur. Therefore, radiographic changes are slight and usually are limited to mild radiographic thickening of the apical periodontal membrane space. However, if a periapical abscess develops as a result of acute exacerbation of a chronic periapical granuloma, a radiolucent lesion is evident. The periapical granuloma represents the result of chronic inflammation at the apex of a nonvital tooth. This is a sequela of pulp necrosis, which may develop through acute or low-grade chronic inflammation. Notably, other, more serious conditions can occur in a periapical position (Box 13-1). Various clinical clues may alert the clinician that the periapical lesion may not be a simple dental granuloma (Box 13-2).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses