Chapter 12 Inlays, onlays and veneers

Inlays and onlays

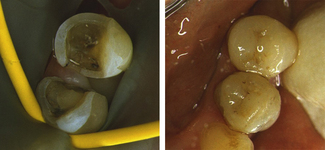

The most common indication for inlays or onlays is extensively restored and weakened teeth. The distinction between the two designs is unclear but simply those restorations without cuspal coverage that remain within the body of the tooth would be considered inlays (Figure 12.1) whereas onlays replace tooth tissue including cusps (Figure 12.2).

Onlays

The most commonly placed partial coverage extracoronal restoration would be an onlay where weakened tooth structure can be protected without further extensive tooth removal. A common indication for an onlay would be a root-filled posterior tooth where cuspal protection is required. Root canal treatment in posterior teeth is usually the result of caries and restorative procedures and, as such, these teeth are extensively broken down and have weakened cusps. The coronal access cavity needed for a root treatment removes the roof of the pulp chamber, weakening the tooth further, and can leave a limited amount of buccal and lingual tooth tissue which might be completely removed if prepared for a crown (Figure 12.3). Preservation of some part of the buccal and lingual tooth helps to retain the core and reduces the need to consider a post, especially in premolar teeth (Figure 12.4). The three-quarter gold crown preparation on a premolar tooth, particularly when only the buccal cusp remains, will preserve tooth tissue but the colour and appearance of gold within the smile line is considered by some to be a disadvantage (see Chapter 8 and Figure 12.5).

Bonding materials (including gold) to a tooth, using adhesive cements, reduces some of the need for conventional principles of retention. Onlays can be considered when there is no or little intracoronal shape to the preparation and where retention is poor. Despite the retention provided by adhesive cement, conventional concepts of tooth preparation for retention should not be ignored and, where possible, should be incorporated into the design of the preparation (Figures 12.2 and 12.6); routine use of adhesive cements to achieve retention poses problems if retrieval is ever necessary.

Dental materials

Gold

Gold onlays need less occlusal and axial reduction than that needed for tooth-coloured materials, as the latter tend to be more brittle and require greater bulk for strength. The ductility of gold and its ability to be highly polished means that it is not as abrasive to the opposing dentition, especially for those patients with tooth wear. All intra- and extra-coronal restorations made from gold need tooth preparation with near parallel walls and an absence of undercuts (Figure 12.7).

Ceramic

Ceramic restorations are indicated where the aesthetic demands of the patient are high. The colour matching of modern porcelains allows the margin between the tooth and material to be almost imperceptible. Where there is a slight difference in colour, the margin of a ceramic inlay/onlay will be obvious (see Figure 12.4) as there is a sudden transition from ceramic to tooth. Ceramic materials, unlike directly placed composite, cannot be placed into progressively thinner layers to blend and merge the colour to that of the tooth, due to their brittleness. This progressive transition with direct composite can camouflage the restoration. Ceramic is a hard material and has high wear resistance; however, it can be abrasive to the opposing dentition when used on the occlusal surfaces, especially if the glaze is lost and the restoration has been adjusted.

The manufacturing techniques used for porcelain and indirect composites generally cannot tolerate such parallel preparations as those produced for a gold inlay, and more tapered walls are needed. Undercuts in the tooth preparation can either be eliminated by further tooth preparation or be blocked out with an adhesive tooth-coloured material. All variants of the preparations should avoid sharp line angles, particularly intracoronally (Figure 12.8).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses