CHAPTER 12. Diseases of the oral mucosa: introduction and mucosal infections

A few mucosal diseases, such as lupus erythematosus, are important indicators of severe underlying systemic disease and rare conditions, such as acanthosis nigricans, can be markers of internal malignancy. Pemphigus vulgaris is potentially lethal, as is HIV infection – which can give rise to a variety of mucosal lesions. Biopsy is mandatory, particularly in the bullous diseases as, in such cases, the diagnosis can only be confirmed by microscopy. In other cases, microscopic findings can be less definite, but often (as in the case of major aphthae for example) serve to exclude more dangerous diseases. Mucosal ulceration – a break in epithelial continuity – is a frequent feature of stomatitis. Important causes are summarised in Table 12.1. However, ulceration is not a feature of all mucosal diseases as discussed below.

| Vesiculo-bullous diseases | Ulceration without preceding vesiculation | |

|---|---|---|

| Infective |

Primary herpetic stomatitis

Herpes labialis

Herpes zoster and chickenpox

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease

|

Cytomegalovirus-associated ulceration

Some acute specific fevers

Tuberculosis

Syphilis

|

| Non-infective |

Pemphigus vulgaris

Mucous membrane pemphigoid

Linear IgA disease

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Bullous erythema multiforme

|

Traumatic

Aphthous stomatitis

Behçet’s disease

HIV-associated mucosal ulcers

Lichen planus

Lupus erythematosus

Chronic ulcerative stomatitis

Eosinophilic ulceration

Wegener’s granulomatosis

Some mucosal drug reactions

Carcinoma (Ch. 17)

|

PRIMARY HERPETIC STOMATITIS → Summary p. 221

Primary infection is caused by Herpes simplex virus, usually type 1, which, in the non-immune, can cause an acute vesiculating stomatitis. However, most primary infections are subclinical. Thereafter, recurrent (reactivation) infections usually take the form of herpes labialis (cold sores or fever blisters).

Transmission of herpes is by close contact and up to 90% of inhabitants of large, poor, urban communities, develop antibodies to herpes virus during early childhood. In many British and US cities, by contrast, approximately 70% of 20-year-olds may be non-immune, because of lack of exposure to the virus. In such countries, the incidence of herpetic stomatitis has declined and it is seen in adolescents or adults, rather than children. It is more common in the immunocompromised, such as HIV infection, when it can be persistent or recurrent.

Clinical features

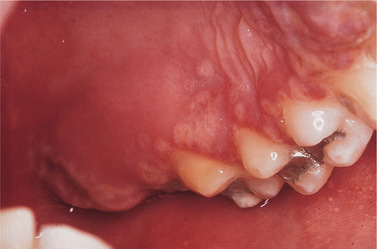

The early lesions are vesicles which can affect any part of the oral mucosa, but the hard palate and dorsum of the tongue are favoured sites (Figs 12.1 and 12.2). The vesicles are dome-shaped and usually 2–3 mm in diameter. Rupture of vesicles leaves circular, sharply defined, shallow ulcers with yellowish or greyish floors and red margins. The ulcers are painful and may interfere with eating.

|

| Fig. 12.1

Herpetic stomatitis. Pale vesicles and ulcers are visible on the palate and gingivae, especially anteriorly, and the gingivae are erythematous and swollen.

|

|

| Fig. 12.2

Herpetic stomatitis. A group of recently ruptured vesicles on the hard palate, a characteristic site. The individual lesions are of remarkably uniform size but several have coalesced to form larger irregular ulcers.

|

The gingival margins are frequently swollen and red, particularly in children, and the regional lymph nodes are enlarged and tender. There is often fever and systemic upset, sometimes severe, particularly in adults.

Pathology

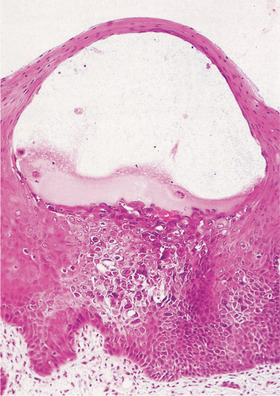

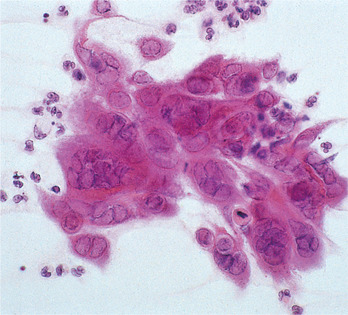

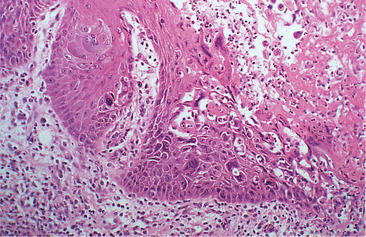

Vesicles are sharply defined and form in the upper epithelium (Fig. 12.3). Virus-damaged epithelial cells with swollen nuclei and marginated chromatin (ballooning degeneration) are seen in the floor of the vesicle and in direct smears from early lesions (Fig. 12.4). Incomplete division leads to formation of multinucleated cells. Later, the full thickness of the epithelium is destroyed to produce a sharply defined ulcer (Fig. 12.5).

|

| Fig. 12.3

Herpetic vesicle. The vesicle is formed by accumulation of fluid within the prickle cell layer. The virus-infected cells, identifiable by their enlarged nuclei, can be seen in the floor of the vesicle and a few are floating freely in the vesicle fluid.

|

|

| Fig. 12.4

A smear from a herpetic vesicle. The distended degenerating nuclei of the epithelial cells cluster together to give the typical mulberry appearance.

|

|

| Fig. 12.5

Herpetic ulcer. The vesicle has ruptured to form an ulcer (right) and the epithelium at the margin contains enlarged, darkly staining virus-infected cells liberating free virus into the saliva.

|

Diagnosis

The clinical picture is usually distinctive (Box 12.1). A smear showing virus-damaged cells is additional diagnostic evidence. A rising titre of antibodies reaching a peak after 2–3 weeks provides absolute but retrospective confirmation of the diagnosis.

Box 12.1

Herpetic stomatitis: key features

• Usually caused by H. simplex virus type 1

• Transmitted by close contact

• Vesicles, followed by ulcers, affect any part of the oral mucosa

• Gingivitis sometimes associated

• Lymphadenopathy and fever of variable severity

• Smears from vesicles show ballooning degeneration of viral-damaged cells

• Rising titre of antibodies to HSV confirms the diagnosis

• Aciclovir is the treatment of choice

Treatment

Aciclovir is a potent antiherpetic drug and is life-saving for potentially lethal herpetic encephalitis or disseminated infection. Aciclovir suspension used as a rinse and then swallowed should accelerate healing of severe herpetic stomatitis if used sufficiently early. Bed rest, fluids and a soft diet may sometimes be required.

Unusually prolonged or severe infections or failure to respond to aciclovir (200–400 mg/day by mouth for 7 days) suggest immunodeficiency and herpetic ulceration persisting for more than a month is an AIDS-defining illness.

HERPES LABIALIS → Summary p. 221

After the primary infection, the latent virus can be reactivated in 20–30% of patients to cause cold sores (fever blisters). Triggering factors include the common cold and other febrile infections, exposure to strong sunshine, menstruation or, occasionally, emotional upsets or local irritation, such as dental treatment. Neutralising antibodies produced in response to the primary infection are not protective.

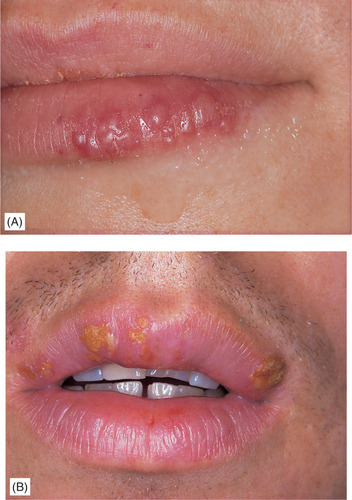

Clinically, changes follow a consistent course with prodromal paraesthesia or burning sensations, then erythema at the site of the attack. Vesicles form after an hour or two, usually in clusters along the mucocutaneous junction of the lips, but can extend onto the adjacent skin (Fig. 12.6).

|

| Fig. 12.6

Herpes labialis. (A) Typical vesicles. (B) Crusted ulcers affecting the vermilion borders of the lips.

|

The vesicles enlarge, coalesce and weep exudate. After 2 or 3 days they rupture and crust over but new vesicles frequently appear for a day or two only to scab over and finally heal, usually without scarring. The whole cycle may take up to 10 days. Secondary bacterial infection may induce an impetiginous lesion which sometimes leaves scars.

Treatment

In view of the rapidity of the viral damage to the tissues, treatment must start as soon as the premonitory sensations are felt. Aciclovir cream is available without prescription and may be effective if applied at this time. This is possible because the course of the disease is consistent and patients can recognise the prodromal symptoms before tissue damage has started. However, penciclovir applied 2-hourly is more effective.

Herpetic cross-infections

Both primary and secondary herpetic infections are contagious. Herpetic whitlow (Fig. 12.7) is a recognised though surprisingly uncommon hazard to dental surgeons and their assistants. Herpetic whitlows, in turn, can infect patients and have led to outbreaks of infection in hospitals and among patients in dental practices. Now that gloves are universally worn when giving dental treatment, such cross-infections should no longer happen. In immunodeficient patients, such infections can be dangerous, but aciclovir has dramatically improved the prognosis in such cases and may be given on suspicion.

|

| Fig. 12.7

Herpetic whitlow. This is a characteristic non-oral site for primary infection as a result of contact with infected vesicle fluid or saliva. The vesiculation and crusting are identical to those seen in herpes labialis.

|

Mothers applying antiherpetic drugs to children’s lesions should wear gloves.

HERPES ZOSTER OF THE TRIGEMINAL AREA → Summary p. 221

Zoster (shingles) is characterised by pain, a vesicular rash and stomatitis in the related dermatome. The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes chickenpox in the non-immune (mainly children), while reactivation of the latent virus causes zoster, mainly in the elderly.

Unlike herpes labialis, repeated recurrences of zoster are very rare. Occasionally, there is an underlying immunodeficiency. Herpes zoster is a hazard in organ transplant patients and can be an early complication of some tumours, particularly Hodgkin’s disease, or, increasingly, of AIDS, where it is five times more common than in HIV-negative persons and potentially lethal.

Clinical features

Herpes zoster usually affects adults of middle age or over but, occasionally, attacks even children. The first signs are pain and irritation or tenderness in the dermatome corresponding to the affected ganglion.

Vesicles, often confluent, form on one side of the face and in the mouth up to the midline (Figs 12.8 and 12.9). The regional lymph nodes are enlarged and tender. The acute phase usually lasts about a week. Pain continues until the lesions crust over and start to heal, but secondary infection may cause suppuration and scarring of the skin. Malaise and fever are usually associated.

|

| Fig. 12.8

Herpes zoster. A severe attack in an older person shows confluent ulceration on the hard and soft palate on one side.

|

|

| Fig. 12.9

Herpes zoster of the trigeminal nerve. There are vesicles and ulcers on one side of the tongue and facial skin supplied by the first and second divisions. The patient complained only of toothache.

|

Patients are sometimes unable to distinguish the pain of trigeminal zoster from severe toothache, as in the patient shown in Figure 12.9. This has sometimes led to a demand for a dental extraction. Afterwards, the rash follows as a normal course of events and this has given rise to the myth that dental extractions can precipitate facial zoster.

Pathology

The varicella-zoster virus produces similar epithelial lesions to those of herpes simplex, but also inflammation of the related posterior root ganglion.

Management

Herpes zoster is an uncommon cause of stomatitis, but readily recognisable (Box 12.2).

Box 12.2

Herpes zoster of the trigeminal area: key features

• Recurrence of VZV infection typically in the elderly

• Pain precedes the rash

• Facial rash accompanies the stomatitis

• Lesions localised to one side, within the distribution of any of the divisions of the trigeminal nerve

• Malaise can be severe

• Can be life-threatening in HIV disease

• Treat with systemic aciclovir, intravenously, if necessary

• Sometimes followed by post-herpetic neuralgia, particularly in the elderly

According to the severity of the attack, oral aciclovir (800 mg five times daily, usually for 7 days) should be given at the earliest possible moment, together with analgesics. The addition of prednisolone may accelerate relief of pain and healing. In immunodeficient patients, intravenous aciclovir is required and may also be justified for the elderly in whom this infection is debilitating.

Complications

Post-herpetic neuralgia mainly affects the elderly and is difficult to relieve (Ch. 34).

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS-ASSOCIATED ULCERATION

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a member of the herpes virus group. Up to 80% of adults show serological evidence of CMV infection without clinical effects, but it is a common complication of immunodeficiency, particularly AIDS. In the latter it can be life-threatening.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses