Bonding and Bonding Agents

Historical Background

Prior to the middle of the twentieth century, dental bonding consisted of various methods of mechanical retention, such as forming undercuts in cavity preparations for amalgam restorations (see Chapter 15). Luting, using zinc phosphate and other nonadhesive dental cements, also falls into this category of bonding (see Chapter 14). In the late 1940s, Oskar Hagger, at the De Trey division of Amalgamated Dental, developed the first bonding agent, Sevriton Cavity Seal. This system was based on glycerophosphoric acid dimethacrylate (see Figure 12-5 on page 263) as a self-adhesive or self-etching component for both enamel and dentin bonding. However, this product had very limited clinical durability because of the large interfacial stresses that developed because of the high polymerization shrinkage and high thermal expansion of the unfilled methacrylate-based resins used at that time. Shortly after, Michael Buonocore investigated stronger acids and discovered that phosphoric acid provides superior enamel etching, and it is still in use today.

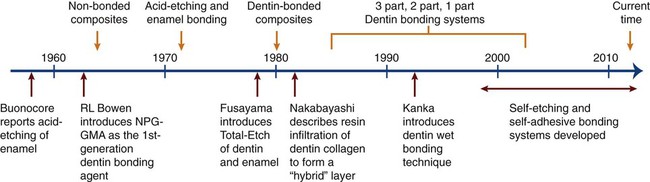

As shown in Figure 12-1, these discoveries of acid etching led to our ability to produce clean, high-energy, roughened enamel surfaces capable of establishing a durable micromechanical retentive interface with resin-based cementing and restorative materials launched the current era of adhesive dentistry. These events soon led to a burgeoning growth in the development of adhesive materials and bonding techniques, into the beginning of the twenty-first century. This progress is summarized in Figure 12-1 and is discussed in detail in several of the later sections of this chapter. At the present time, adhesive bonding can only be relied on for long-term retention in very select circumstances using highly specialized materials and clinical techniques, many of which are discussed in detail below. Nevertheless, dentistry is now well into the era of adhesive bonding and its associated field of esthetic dentistry.

Applications for Bonding

Today, acid etching is one of the most effective ways to promote restoration retention and to ensure a sealed interfacial joint at restoration margins. This procedure has markedly expanded the use of resin-based restorative materials because it provides a strong, durable bond between resin and tooth structure and has formed the basis from many innovative dental procedures as diverse as orthodontic bracket bonding and porcelain laminate veneer bonding. Additional applications include pit and fissure sealants; amalgam bonding; both enamel and dentin bonding; adhesive cements, including glass-ionomer restorative materials; and endodontic sealers. Many of these applications are discussed in this chapter; however, other bonding applications are also discussed in greater detail throughout the book but with particular emphasis in Chapters 2, 13, 14, 15, and 18.

Mechanisms of Adhesion

The science of adhesion has been covered in Chapter 2. In this chapter, only those principles of adhesion needed for an understanding of dental bonding will be discussed.

As explained in Chapter 2, wettability of a liquid on a solid can be characterized by the contact angle that forms between a liquid and solid, as measured within the liquid. Categories of wettability include “mostly nonwetting” (>90 degrees), “absolutely no wetting” (180 degrees), “mostly wetting” (<90 degrees), and absolute wetting (0 degrees). See Figure 2-15 for a schematic illustration of wetting situations.

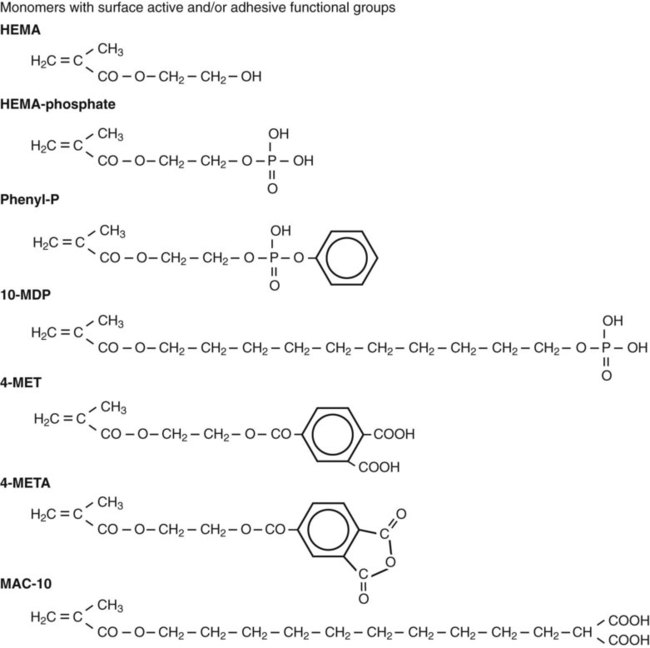

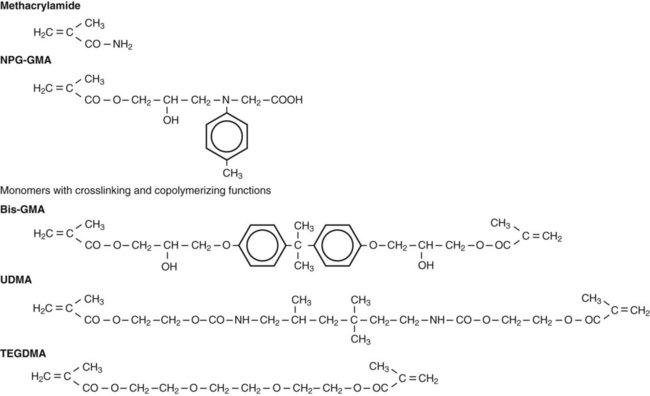

Although wetting is an essential requirement for intraoral adhesion, it is not sufficient to ensure durable bonding. As explained below, to achieve strong bonding through the micromechanical interlocking mechanism, wetting monomers must intimately adapt to enamel and fill enamel surface irregularities and/or infiltrate into a demineralized collagen network in dentin. Some acid monomers with a phosphate (e.g., phenyl-P) or carboxyl group (e.g., 4-MET) have the additional potential of forming chemical bonds with calcium in the residual tooth tissue. The chemical structures of these acidic monomers are shown later in Figure 12-4 and Figure 12-6.

Acid-Etch Technique

Enamel Etching

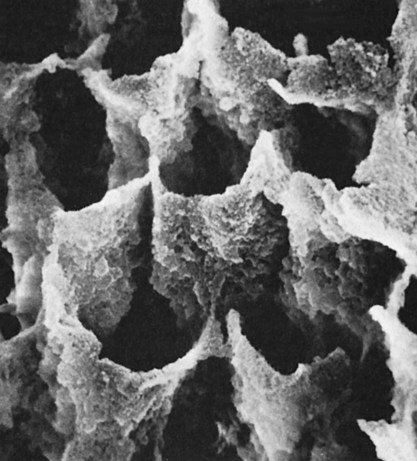

The first meaningful demonstration of intraoral adhesion was reported by Michael Buonocore (1955). Buonocore etched enamel surfaces with various acids, placed an acrylic restorative material on the micromechanically roughened surfaces, and found a great increase in the resin–enamel bond strength (~20 megapascals [MPa]). One of the surface conditioning agents he used, phosphoric acid, is still the most widely used etchant today for bonding to both enamel and dentin. Depending on the concentration, phosphoric acid removes the smear layer and about 10 microns of enamel to expose prisms of enamel rods to create a honeycomb-like, high energy retentive surface (Figure 12-2). The higher surface energy ensures that resin monomers will readily wet the surface, infiltrate into the micropores, and polymerize to form resin tags. The pattern of etching enamel may vary from selective dissolution of either the enamel rod centers (type I etching) as shown in Figure 12-2, or the peripheral areas (type II etching) as indicated by the resin tags in Figure 12-3. In either case, the resin tags are approximately 6 µm in diameter and 10 to 20 µm in length and lead to micromechanical interlocking.

Dentin Etching

As illustrated in Figure 12-1, dentin etching did not gain wide acceptance until Fusayama introduced the total-etch concept in 1979. For this method, both dentin and enamel are etched simultaneously, typically using 37% phosphoric acid. His study demonstrated that not only was restoration retention substantially increased but also pulp damage did not occur as had been generally assumed. A subsequent study by Nakabayashi et al. (1984) revealed that hydrophilic resins can infiltrate the surface layer of acid-demineralized collagen fibers that is produced in etched dentin and it can form a layer of resin-infiltrated dentin with high cohesive strength. Such a hybrid layer structure forms very strong resin bonds through the development of an interpenetrating network of polymer and dentinal collagen, together with numerous micromechanical interlocks at the resin–hybrid layer interface. By the early 1990s, dentin etching had gained worldwide acceptance. Since the total-etch technique usually involves etching with an acid followed by rinsing to remove the acid, this technique is also known as the etch-and-rinse technique.

Process and Procedural Factors

Rinsing and Drying Stage

Once the tooth is etched, the acid should be rinsed away thoroughly with a stream of water for about 20 seconds, and the rinsed water must be removed. When enamel alone is etched and is to be bonded with a hydrophobic resin (e.g., bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate [bis-GMA]–based resin; see Chapter 13), it must be dried completely with warm air until it takes on a white, frosted appearance. Dentin, in contrast, cannot withstand such aggressive drying, which would cause bond failure because of the formation of impermeable, collapsed collagen fibers. In the total-etch technique, a dentin bonding agent and primer must be used that are compatible with both moist dentin and moist enamel.

Cleanness of the Bonding Surfaces

The etched surfaces must be kept clean (free of contaminants) and sufficiently dry until the resin is placed to form a sound mechanical bond. Although etching raises the surface energy, contamination can readily reduce the energy level of the etched surface. Reducing the surface energy, in turn, makes it more difficult to wet the surface with a bonding resin that may have too high a surface tension to wet the contaminated surface. (Surface energy and wetting are described in detail in Chapter 2.) Thus, even momentary contact with saliva or blood can prevent effective resin tag formation and severely reduce the bond strength. Another potential contaminant is oil that is released from the air compressor and transported along the air lines to the air–water syringe. If contamination occurs, the contaminant should be removed, and the surface should be etched again for 10 seconds.

Other Factors

The acid-etch technique was not widely used in the years immediately following its introduction (see Figure 12-1). The principal reason was the inferior properties of the acrylic filling materials used at that time. With those resins, curing (>6 vol% shrinkage) and thermal dimensional changes (coefficients of thermal expansion in excess of 100 parts per million per degree Celsius [ppm/°C]) generated interfacial stresses sufficient to rupture the bond to etched enamel. After highly filled resin-based composites were marketed beginning in the mid-1960s, the acid-etch technique was “rediscovered.” Acid etching is a very effective way to improve bonding and durability as well as to ensure a sealed interface. It has markedly expanded the use of resin-based restorative materials because it provides a strong bond between resin and teeth, forming the basis for many innovative dental procedures.

Dentin Bonding Agents

1. Micromechanical interlocking, chemical bonding with enamel and dentin, or both

2. Copolymerization with the resin matrix of composite materials

Before the total-etch technique was adopted, enamel bonding agents were used only to enhance the wetting and adaptation of resin to conditioned enamel surfaces. Generally, enamel bonding agents are made by combining different dimethacrylates from resins of composite materials (e.g., bis-GMA) with diluting monomers (e.g., triethylene glycol dimethacrylate [TEGDMA], Figure 12-4) to control viscosity and to enhance wetting. These agents have no potential for adhesion, but they improve micromechanical bonding by optimal formation of resins tags within the enamel. Because enamel can be kept fairly dry, these rather hydrophobic resins work well as long as they are restricted to enamel.

1. Adequate removal or dissolution of the smear layer from enamel and dentin

2. Maintenance or reconstitution of the dentin collagen matrix

4. Efficient monomer diffusion and penetration

Irrespective of the number of bottles or components (see Figure 12-7 and Table 12-1), a typical dentin bonding system includes etchants, resin monomers, solvents, initiators and inhibitors, fillers, and sometimes other functional ingredients such as antimicrobial agents.

TABLE 12-1

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses