Spread of Oral Infection

To a large extent, certain anatomic features determine the actual direction that the infection may take (Fig. 11-1).

It is usually easy to determine whether an infection is present or not, based on local and systemic factors. Local changes include pain, swelling, restriction of movement, surface erythema, and pus formation. Systemic factors include toxic appearance, fever, lymphadenopathy, malaise, and increased white blood cell count.

Cellulitis: (Phlegmon)

Clinical Features

The patient with cellulitis of the face or neck originating from a dental infection is usually moderately ill and has elevated temperature and leukocytosis. One feels painful swelling of the soft tissues involved that are firm and brawny. Much of the swelling is due to inflammatory edema. (Fig. 11-2). If the superficial tissue spaces are involved, the skin is inflamed, has an orange peel appearance and is even purplish sometimes. In the case of inflammatory spread of infection along deeper planes of cleavage, the overlying skin may be of normal color. In addition, regional lymphadenitis is usually present.

Figure 11-2 Cellulitis of the face. (Courtesy of Dr RS Nealakandan, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai).

As the typical facial cellulitis persists, the infection frequently tends to become localized, and a facial abscess may form. When this happens, the suppurative material present seeks to ‘point’ or discharge upon a free surface (Fig. 11-3). If early treatment is instituted, a resolution usually occurs without drainage through a break in the skin.

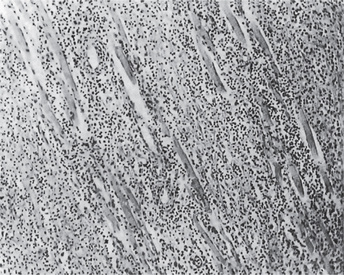

Histologic Features

A microscopic section through an area of cellulitis shows only a diffuse exudation of polymorpho-nuclear leukocytes and occasional lymphocytes, with considerable serous fluid and fibrin, causing separation of connective tissue or muscle fibers (Fig. 11-4). Cellulitis presents only a nonspecific picture of diffuse acute inflammation.

Infections of Specific Tissue Spaces

Spread of Infection from Mandibular Teeth

Premolars may form vestibular abscesses, and lingual perforation may form sublingual abscesses.

Secondary sites of spread are the parotid space, temporal, infratemporal, and pharyngeal spaces.

Manifestations of Various Space Infections

The buccal space is bounded medially by the buccinator muscle and its covering buccopharyngeal fascia; laterally by the skin and subcutaneous tissues; anteriorly by the posterior border of the zygomaticus major muscle above; the depressor anguli oris muscle below; and posteriorly by the anterior edge of the masseter muscle. Superiorly, the space is bounded by the zygomatic arch (Fig. 11.5A), and inferiorly by the lower border of the mandible.

Figure 11-5 Infections involving spaces.

(A) Buccal space. (B) Submasseteric space. (C) Submandibular space. (D) Submental space (Courtesy of Dr RS Nealakandan, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai).

Infratemporal Space

Boundaries

The infratemporal space is bounded anteriorly by the maxillary tuberosity; posteriorly by the lateral pterygoid muscle, the condyle and temporal muscle; laterally by the tendon of the temporal muscle and the coronoid process; and medially by the lateral pterygoid plate and inferior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle. The infratemporal space contains the pterygoid plexus, the internal maxillary artery, the mandibular nerve, mylohyoid nerve, lingual nerve, buccinator nerve and chorda tympani nerves, and the external pterygoid muscle.

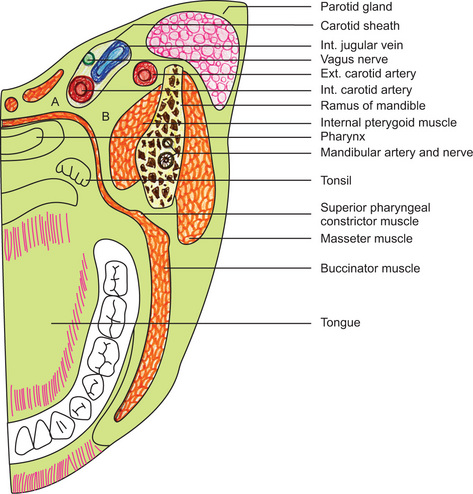

Lateral Pharyngeal Space Boundaries

The lateral pharyngeal space, one of the parapharyngeal spaces, is bounded anteriorly by the buccopharyngeal aponeurosis, the parotid gland and the pterygoid muscles, posteriorly by the prevertebral fascia, laterally by the carotid sheath and medially by the lateral wall of the pharynx (Fig. 11-6).

Figure 11-6 Horizontal section through the head at the level of the mandibular occlusal plane.

The parapharyngeal spaces are indicated: (A) retropharyngeal space, (B) lateral pharyngeal space.

Clinical Features

Infection of this space with abscess formation may impinge on the pharynx, causing difficulty in swallowing and even in breathing. The pain also may be referred to the ear. Trismus is usually present. An anesthetic may be required to confirm the diagnosis. The tonsillar pillars and tonsil are displaced medially, and so is the uvula. This infection must be differentiated from a peritonsillar abscess. In the latter condition trismus is less severe or absent, and the tonsil, instead of being normal, is enlarged and inflamed.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Infections of Specific Tissue Spaces

. Infections of Specific Tissue Spaces . Ludwig’s Angina

. Ludwig’s Angina . Maxillary Sinusitis

. Maxillary Sinusitis . Focal Infection

. Focal Infection