Chapter 10

Sedation for the Pediatric Patient

Introduction

Only a few short decades have witnessed a multitude of significant changes associated with the pharmacological management of children for dental and medical procedures. As shown in the previous chapter, there are many possible reasons for the change. Importantly, these include the development and implementation of sedation guidelines by professional groups and the unpredictable but constantly evolving professional and societal influences affecting behavioral management techniques, including sedation practices. There seems to be a tendency, however, for pediatric dentists to practice pharmacological management of children in a similar vein to that in which they were trained (Houpt 2002). Thus, the practice of sedation in the United States has likely retained much from the past.

One aspect of pharmacological management that remains constant is the quest for the “magic bullet.” The “magic bullet” is thought of as a single sedative agent or concoction of sedative agents which, when given to a child patient, will: a) ensure that the child is peaceful in demeanor and responds favorably during the procedure, b) harbors enough working memory to retain the impression of a pleasant experience at the dental office, c) is minimally affected by invasive dental interventions from physiological, behavioral, and emotional perspectives, and d) is always safe in the hands of the clinician. So far, the only “magic bullet” that comes close but does not fully satisfy this idyllic state is that of general anesthesia. One might predict that the future will see such a “magic bullet,” but not in the same heuristic conceptualization that we currently embrace. Rather, it may involve the use of some selective, reversible effect on various neuroanatomical loci of the brain using an, as yet, undiscovered psychopharmacological concoction or other interventional procedure.

Sedation and Pediatric Dentistry

One popular method used today in clinical care of patients who experience fear, anxiety, and/or pain is pharmacological intervention. In fact, sedation of children is a very common and accepted modality of patient management during potentially painful procedures. Its popularity is due, in part, to its effective and efficient ability to overcome in variable degrees the mental and emotional anguish and behavioral expressions of the patient who otherwise is unable to provide satisfactory personal management of the distressing situation.

The process and need for safety in performing sedation during dental procedures involves several factors that are directed toward positive general outcomes. Some of these factors can be seen in Table 10-1. Clinicians must have a strong cognitive understanding of clinical expertise in, and respect for each of these factors, often reflected in the concept of professional competency. Unfortunately, little is currently known about practitioner competency surrounding the knowledge of and adherence to these factors, either in the educational or practice communities. Indirectly, information through surveys over the decades has suggested that many practitioners perform sedations on a regular basis (Houpt 1989, 1993, 2002), but documented information of the details of the sedations and even their effectiveness are mostly non-existent. Nonetheless, several important factors, which the dentist should have gleaned through formal training and experience, are discussed briefly in the following sections.

The Child

Essential knowledge of the child’s age, cognitive development, temperament, and coping styles becomes key to planning and negotiating interactions aimed at arriving at a safe and successful clinical outcome (see Chapter Two). Usually, children under three years of age are not easily managed during stressful or painful procedures using behavioral interactive techniques. The likelihood that such techniques will become more successful increases once the youngster has a better comprehension and mastery of speech, symbolic manipulations, and coping strategies. Thus, pharmacological management of the child who is under three years becomes a more promising and rational approach in managing behavior, assuming the depth of the sedation is sufficient to overcome the child’s natural instincts of fight or flight during the procedure. Generally, deep sedation (DS) or general anesthesia (GA) is needed, but they carry a greater risk for the child and clinical team.

Table 10-1. Major factors and their considerations in performing sedations.

| Major factors | Considerations |

| Child characteristics | Age, cognition, temperament, style of coping, parent-child relationship |

| Drug characteristics | Dose and concentration, mechanism of action, effects, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, adverse events, contraindications, formulations |

| Protocol | Standardized process, checks and balances, quality improvement measures |

| Patient monitoring | Monitors, significant and implications of measures monitored |

| Practitioner training | Breadth and types of experiences, programmatic versus empirical influences, recognition and response to patient signs and symptoms |

| Clinical staff knowledge | Similar to practitioner training |

| Sedation guidelines | Knowledge of and adherence to guidelines |

| State rules and regulations | Knowledge of and adherence to state regulations |

| Emergency prevention and management | Training, recognition, and interventional abilities |

Children cope with varying degrees of success during challenging clinical situations. There are few studies in dentistry investigating cognitive coping strategies, parental or staff-assisted interventions (e.g., distraction or breathing exercises), or other mechanisms used to cope with acute or chronic pain and perceived stress. However, interventional studies designed to minimize anxiety, stress, and pain in non-dental settings have been investigated by others. For convenience, they are listed with the references at the end of the chapter. Investigations into how children cope with stressful situations potentially involving pain have led to such concepts as information-seeking and information-limiting individuals (Fortier et al. 2009). In other words, some children do better when told about details of a procedure that they will undergo, whereas others use different techniques, including limiting information about the procedure.

Temperament may be defined as how a child typically responds to a novel environment as well as the child’s basic daily expression pattern in a host of solitary and social situations. It was initially described in relation to the clinical environment in the 1960s by Thomas and Chess (1963). As such, temperament has received considerable attention in explaining some behaviors associated with various settings (Lopez et al. 2008; Fortier et al. 2010; Lee and White-Traut 1996). Several characteristics supporting differences in temperament have been described (Lochary et al. 1993) and can be seen in Table 10-2.

Table 10-2. Domains of temperament.

| Parameter | Characteristic |

| Sensitivity | threshold level for change in environment |

| Approachability | initial response to new settings |

| Adaptability | response over time to new settings |

| Mood | tendency toward happy or unhappy attitude |

| Distractibility | tendency to be sidetracked |

| Activity | daily amount of energy expended |

| Regularity | predictability in daily routine |

| Intensity | amount of energy in response to setting |

| Persistence | ability to stick to task |

Temperamental characteristics of children are thought to be related to child behavior in clinical situations (Caldwell-Andrews and Kain 2006; Tripi et al. 2004). Interestingly, there is a significant amount of information concerning the contribution of child temperament to behaviors witnessed in the dental environment (Arnrup et al. 2003; Arnrup et al. 2007; Klingberg and Broberg 1998, 2007) Children can generally be divided into three groups: a) easy—those are very interactive, friendly, and easily managed; b) slow-to-warm up—those who generally do well with appropriate guidance but need some time to overcome minor anxieties; and c) difficult—those who are withdrawn and display overt disruptive behaviors with little provocation (Lochary et al. 1993). The results of some studies suggest that shy children in the dental setting express more distress and negative behaviors in response to dental procedures (Jensen and Stjernqvist 2002; Quinonez et al. 1997), whereas those who are adaptable and approachable exhibit less disruptive and more appropriate interactive behaviors (Lochary et al. 1993; Radis and Wi 1994). A clinician should always be cognizant of children’s behaviors pre-operatively in hopes of finding clues that may aid in anticipating interactions with the child once dental procedures begin. For instance, a concerted effort should be made to observe the interaction of the dental staff with children during initial introductions and exchanges of pleasantries, patient weighing, and introduction to the office in general and the clinical operatory in particular. These interactions can help to predict behavior and anticipate potential behavior management strategies.

A parent’s demeanor, body language, concerns, desires, anxieties, and opinions are also important considerations. Parents usually have beliefs and value systems that tend to fit their generation, lifestyle, and life experiences. It is appropriate for the practitioner to ascertain the parent’s opinion in discussing behavior management possibilities.

There is some evidence suggesting that parenting skills have changed over recent decades and that these changes influence how children tend to respond in the dental environment, as well as in other social settings (Casamassimo et al. 2002; Schorr 2003). Practitioners report that children tend to cry and are more difficult to manage than in the past. Furthermore, some view today’s parents, compared to recent generations, as more liberal in rearing their children. As an extension of that view, many believe that this less-involved parenting style is a detrimental trend in that parents fail to set limits and are less involved in guiding their children in psychosocial and socialization processes. Even the concept of the family is different than it was when this textbook was initially written (see Chapter Four). As a newer generation of professionals transition into providing care, their attitudes, opinions, and orientations toward delivery of care may change, reflecting similar sentiments of parents of their age. It will remain speculative as to what management technologies may prevail in the future. But it is possible, based on societal trends today, that a greater reliance on pharmacological management will predominate in managing children for medical and dental procedures.

Patient Assessment

One of the most important and comprehensive aspects in the decision to use pharmacological agents in aiding the management of the child is that of patient assessment. Patient assessment includes a detailed review of the medical history and major physiological systems (e.g., cardiovascular) and performing a physical assessment of the child, focusing on auscultation of the chest and heart, viewing the upper airway structures including tonsils, ascertaining an impression of the patient’s behavior and temperament, and determining the patient’s amount of dental needs. Medical consults following the initial review of the patient’s conditions are also a part of this process.

By performing these preliminary procedures, one is able to determine the physical risk and status of the patient in undergoing the sedation and dental procedure, the drug(s) and dose(s) selected, and possibly an impression of the likelihood of a successful outcome. A similar process occurs when assessing a patient for general anesthesia, with the outcome being a physical risk category assigned to the patient. The standard physical risk categories used in medical and dental care are those of the American Society of Anesthesiology (i.e., ASA classifications) and can be seen in Table 10-3.

The review of systems and medical history implies asking appropriate questions and, if anything other than “normal” arises, follow-up queries to determine the issue and its impact, medications, hospitalizations, acute or chronic home care, and outcome of any previous intervention. If there is or has been a problem with a system, a consult with the patient’s primary care physician is often advisable.

Table 10-3. American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) physical risk categories.

| ASA Class* | Patient Status | Comment |

| I | A normal, healthy patient. | No organic, physiologic, or psychiatric disturbance, healthy with good exercise tolerance |

| II | A patient with mild systemic disease. | No functional limitations, has a well-controlled disease of one body system |

| III | A patient with severe systemic disease. | Some functional limitation, has a controlled disease of more than one body system or one major system, no immediate danger of death |

| IV | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life. | Has at least one severe disease that is poorly controlled or at end stage |

| V | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation. | Not expected to survive > 24 hours without surgery, imminent risk of death |

*There is an ASA VI, but it refers to a brain-dead individual whose organs may be harvested.

Auscultation of the chest using a stethoscope is needed to confirm that the intrathoracic airway is clear and not congested or indicative of other abnormalities (e.g., asthmatic wheezing). Typically, placement of the bell on the various fields of the chest and back is done. In preschoolers, another good location to hear breath sounds in under the arm pit and lateral border of the chest. The primary goal in listening to the heart is determining if there is a regular rate and rhythm (e.g., sinus rhythm). If there is anything unusual or different from a typical “lub-dub” of each cardiac cycle, or if any other sound is heard, a consult with the child’s physician is usually recommended. Sites can be found on the Internet allowing one to hear differences between normal and abnormal respiratory and cardiac sounds. A visit to those websites is highly recommended. Listen to the sounds to gain a basic appreciation of what is normal and abnormal.

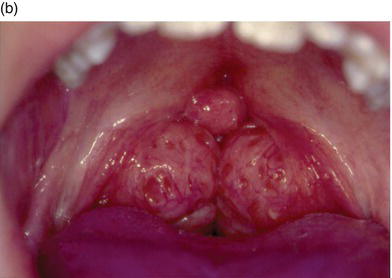

The size of the tonsils is very important in appreciating the amount of airway space that they occupy between the anterior and posterior pillars separating the oral from the pharyngeal portion of the oropharynx (Figure 10-1). Strong consideration of the risk of large tonsil size is imperative, especially if the likelihood that unconsciousness may occur during sedation. Tonsils greater than 50% of the airway diameter are usually contraindicated with drugs like chloral hydrate. Chloral hydrate may increase the probability of airway blockage due to relaxation of the tongue muscles, which, due to gravity in a supine patient, fall backward against soft tissue. A very important question that should always be asked of the parent is whether the child snores during sleep. The likelihood of snoring increases as the size of the tonsils increase.

It is rare that one cannot visualize the tonsils and transitional aspects of the portion of the oropharynx. If the child is fairly cooperative, one may ask them to point their chin toward the ceiling while in a supine position, open as wide as possible, and say a soft “ahhh.” The clinician seated directly behind the patient with good lighting should be able to judge the size of the tonsils and how much of the patent space they occupy. If a child is uncooperative, the following technique can be used to visualize the tonsils. A mouth mirror or tongue blade can be placed on the posturing tongue and slowly moved distally until the gag reflex is triggered. The clinician has to quickly observe the tonsil size during the gag movement, where the tonsils and soft tissue collect in the center of the airway space and move slightly cephalad. The patient will not vomit, but the clinician has to be prepared to observe the tissues during this quick reflex. A second gag attempt is not recommended.

Figure 10-1. Tonsil size is very important in appreciating the amount of airway space that they occupy between the anterior and posterior pillars separating the oral from the pharyngeal portion of the oropharynx: visible tonsils of average size (a) versus enlarged tonsils which may result in airway blockage (b).

Finally, an assessment of the child’s dental needs is critical in terms of the number of teeth or quadrants of dentistry requiring treatment, the technical challenge of the procedures, and the degree of immobility needed for the type of procedures anticipated. These, along with the child’s temperament, are important variables in deciding the selection of agents and their doses prior to preparing the sedation “cocktail.” For instance, an ultra-short procedure such as extraction of the maxillary primary incisors may only require a moderate dose of midazolam. Midazolam has a rapid onset but a short duration of action, whereas two or more quadrants of dental restorations may require a triple combination of drugs such as low dose chloral hydrate, meperidine, and hydroxyzine. This combination affords the dentist a longer working time. Those who do not vary the drug regimens or doses are likely to have a lower rate of successful sedations than those who have the training and skills associated with various drug regimens.

Sedation Protocol

Establishing and adhering to a good sedation protocol will facilitate pharmacological management of the child and minimize the likelihood of making an error within a sequence of activities associated with the delivery of dental care. Another benefit of relying on a regular and standardized procedural sequence is that it allows the incorporation and synchronization of other staff or colleagues as collaborators in safeguarding patient welfare. As a team, a set of checks throughout the process diminishes errors of omission, overt forgetfulness, and probabilities of sequential flaws. A sense of teamwork will evolve and can be strengthened by regular reviews and application of risk management principles, with the goal of continual quality improvement.

There are key steps within a protocol that should be highlighted for emphasis in guaranteeing the best possible outcome for the patient. They are important because they increase favorable interactions between controlled and uncontrolled factors (e.g., dental procedure versus child temperament, respectively), provide primary and secondary defenses against procedural hazards, and communicate a strong feeling of competency in performing professional duties. An example of a sedation protocol that may reflect these principles is shown in Table 10-4.

Table 10-4. An example of a sedation protocol.

| Timing | Steps |

| Pre-sedation prior to sedation appointment | Behavioral assessment Dental examination and needs Medical and dental history Physical examination, including airway Informed consent with risks and benefits Pre-operative counseling and written instructions for parents Consults, as needed Office policy and requests during sedation visit Financial considerations State and professional regulations/guidelines |

| Pre-sedation steps on day of sedation | Review of all of the above for completeness Matching temperamental factors with selection of drug(s) and dose(s) Drawing up drug(s) in presence of colleague/staff Drug administration method and considerations Clinical monitoring (or affixing monitors, as needed) during latency period between administration of drug and start of operative procedure Feedback to parents, as needed Safety interventions, as needed (e.g., emesis and decision to continue) |

| Intra-operative steps | Dental instruments, supplies, /> |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses