Diseases of the Pulp and Periapical Tissues

Diseases of Dental Pulp

The diseases of the dental pulp to be considered in this section are those occurring chiefly as sequelae of dental caries. Those reactions following various physical and chemical injuries are discussed in Chapter 12 on Physical and Chemical Injuries of the Oral Cavity. The sequential conditions are almost exclusively inflammatory and do not differ basically from inflammation elsewhere in the body.

Etiologic Factors

The significance of microorganisms in the etiology of pulpitis has been confirmed by Kakehashi and his associates, who produced surgical pulp exposures in germ-free rats. It was found that no devitalized pulps or periapical infections developed even when gross food impactions existed. By contrast, conventional animals rapidly developed complete pulpal necrosis.

Classification of Pulpitis

Focal Reversible Pulpitis

Histologic Features

Focal pulpitis is characterized microscopically by dilatation of the pulp vessels (Fig. 10-1). Edema fluid may collect because of damage to the capillary walls, allowing actual extravasation of red blood cells or some diapedesis of white blood cells. Slowing of the blood flow and hemoconcentration due to transudation of fluid from the vessels conceivably could cause thrombosis. The belief has prevailed also that self-strangulation of the pulp may occur as a result of increased arterial pressure occluding the vein at the apical foramen. Boling and Robinson argued that this belief is incorrect because the pulp may have several afferent and efferent vessels and several foramina, making self-strangulation unlikely.

Acute Pulpitis

Clinical Features

Severe pain is more likely to be present when the entrance to the diseased pulp is not wide open. The pulpal pain is not only caused by the pressure built-up due to lack of escape of inflammatory exudates but also by the pain producing substances released by the inflammatory reaction. Caviedes-Bucheli J and coworkers have demonstrated that, the receptors for substance P, a neurotransmitter in the pain fiber system, increases during inflammation of pulp. Soon there is rapid spread of inflammation throughout the pulp with pain and necrosis. Until this inflammation or necrosis extends beyond root apex, the tooth is not particularly sensitive to percussion. When a large open cavity is present, there is no opportunity for a build-up of pressure. Thus the inflammatory process does not tend to spread rapidly throughout the pulp. In such a case the pain experienced by the patient is a dull, throbbing ache, but the tooth is still sensitive to thermal changes. Mobility and sensitivity to percussion are usually absent.

Early in the course of the disease, the polymorphonuclear leukocytes are confined to a localized area, and the remainder of the pulp tissue appears relatively normal. The rise in pressure in the pulp associated with an inflammatory exudate causes local collapse of the venous part of the circulation. This leads to local tissue hypoxia and anoxia, which in turn may lead to localized destruction and the formation of a small abscess, known as a pulp abscess, which contains pus arising from breakdown of leukocytes and bacteria as well as from digestion of tissue (Figs. 10-2, 10-3). This necrotic zone contains polymorphonuclear leukocytes and histiocytes. Abscess formation is most likely to occur when the entrance to the pulp is a tiny one and there is lack of drainage. The chemical mediators released from the necrotic tissue lead to further inflammation and edema. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), a multifunctional cytokine mediates epithelial mesenchymal interaction, and is involved in the development and regeneration of various tissues including teeth. Ohnishi T et al, have reported the presence of HGF during acute inflammation of the pulp. Interleukin-8 level in the exudate of the acute pulpitis is higher than that in chronic pulpitis as shown by Guo X et al.

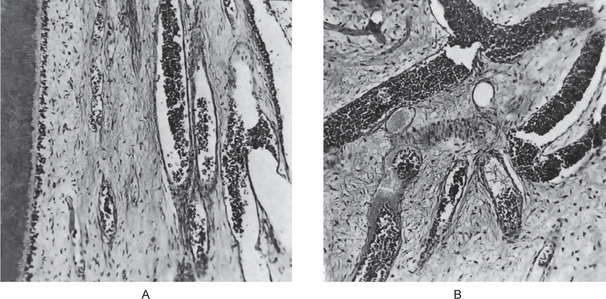

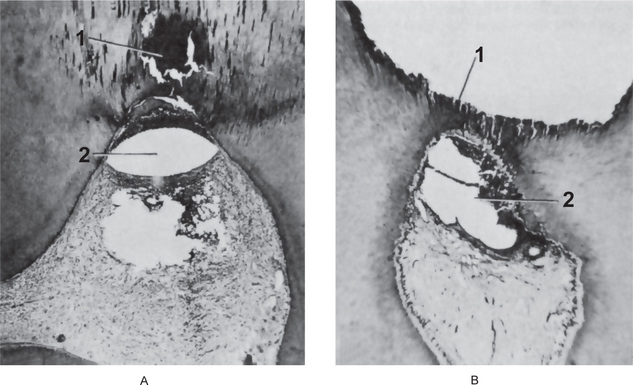

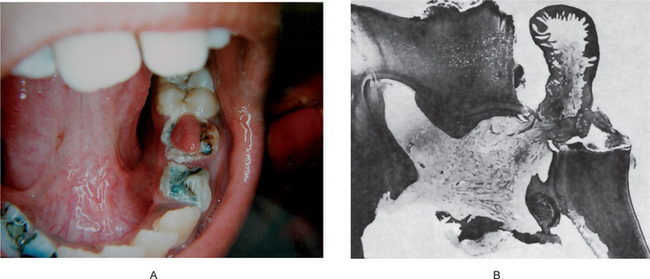

Figure 10-2 Acute pulpitis with pulp abscess formation.

There is diffuse inflammation of the pulp chamber in A beneath the carious lesion (1) with the formation of a circumscribed focus of suppuration, a pulp abscess (2). In B, the carious lesion (1) has evoked only a focal inflammation of the pulp with abscess formation (2).

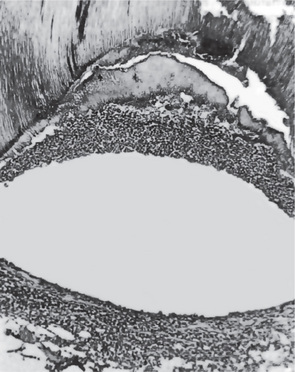

Figure 10-3 Pulp abscess.

The high-power photomicrograph of Figure 10-2 A, shows the void caused by the loss of the suppurative contents of the abscess and the limiting band of leukocytes.

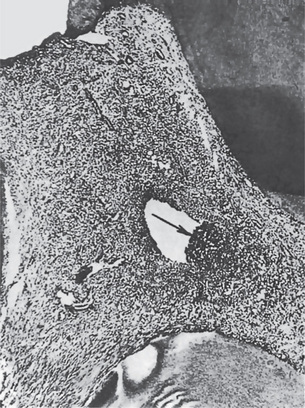

Eventually, in some cases in only a few days, the acute inflammatory process spreads to involve most of the pulp so that neutrophilic leukocytes fill the pulp. The entire odontoblastic layer degenerates. If the pulp is closed to the outside, there is considerable pressure formed, and the entire pulp tissue undergoes rather rapid disintegration. Numerous small abscesses may form, and eventually the entire pulp undergoes liquefaction and necrosis. This is sometimes referred to as acute suppurative pulpitis (Fig. 10-4).

Treatment and Prognosis

There is no successful treatment of an acute pulpitis involving most of the pulp that is capable of preserving the pulp. Once this degree of pulpitis occurs, the damage is irreparable. Occasionally, acute pulpitis—especially with an open cavity—may become quiescent and enter a chronic state. This is unusual; however, and appears to occur most frequently in persons who have a high tissue resistance or in cases of infection with microorganisms of low virulence. In very early cases of acute pulpitis involving only a limited area of tissue, there is some evidence to indicate that pulpotomy (removal of the coronal pulp) and placing a bland material that favors calcification, such as calcium hydroxide, over the entrance to the root canals may result in survival of the tooth. This technique is also used in cases of mechanical pulp exposures without obvious infection (Fig. 10-5). Teeth involved with acute pulpitis may be treated by filling the root canals with an inert material, provided the pulp chamber and root canals can be sterilized.

Chronic Pulpitis

Chronic pulpitis may arise on occasion through quiescence of a previous acute pulpitis, but more frequently it occurs as the chronic type of disease from the onset. As in most chronic inflammatory conditions, the signs and symptoms are considerably milder than those in the acute form of the disease. A special form of chronic pulpitis known as chronic hyperplastic pulpitis has characteristic features and will be described separately.

Histologic Features

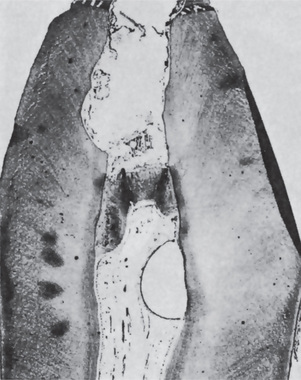

Chronic pulpitis is characterized by infiltration of the pulp tissue by varying numbers of mono-nuclear cells, chiefly lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 10-6) and more vigorous connective tissue reaction. Bacterial products may act as antigens and the dendritic cells of the pulp capture the antigens, migrate to lymph nodes and present them to lymphocytes. These activated T cells then leave the lymph nodes and reach the pulp. Capillaries are usually prominent; fibroblastic activity is evident; and collagen fibers are seen, often gathered in bundles. There is sometimes an attempt by the pulp to ward off the infection through deposition of collagen fibers around the inflamed area. The tissue reaction may resemble the formation of granulation tissue. When this occurs on the surface of the pulp tissue in a wide-open exposure, the term ulcerative pulpitis is applied. With bacterial stains, microorganisms may be found in the pulp tissue, especially in the area of a carious exposure. In some cases, the pulpal reaction vacillates between an acute and a chronic phase. This holds true not only for diffuse inflammation but also for that form of pulp disease characterized by pulp abscess formation. Thus a pulp abscess may become quiescent and be surrounded by a fibrous connective tissue wall, which is known as the pyogenic membrane.

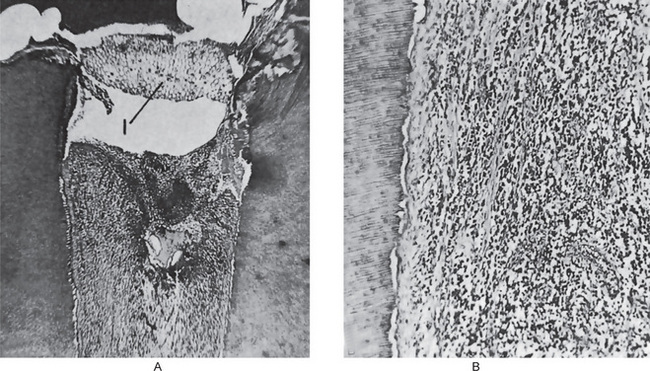

Figure 10-6 Chronic pulpitis.

(A) The pulp of this tooth shows diffuse involvement by chronic inflammatory cells. The entrance to the pulp chamber is wide open (open pulpitis), but contains food debris (1). (B) In the high-power photomicrograph there is seen diffuse infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells with fibrosis and loss of the odontoblastic layer.

Chronic Hyperplastic Pulpitis: (Pulp polyp)

Clinical Features

Chronic hyperplastic pulpitis occurs almost exclusively in children and young adults who possess a high degree of tissue resistance and reactivity, and readily respond to proliferative lesions. It involves teeth with large, open carious lesions. A pulp so affected appears as a pinkishred globule of tissue protruding from the pulp chamber and not only fills the caries defect but also extends beyond (Fig. 10-7). Because the hyperplastic tissue contains few nerves, it is relatively insensitive to manipulation. However, Southam and Hodson have found that sometimes innervation of polyps may be quite rich and have stated that the number of nerve fibers in pulp polyps cannot be presumed to be directly related to the sensory acuity found on clinical examination. They have even noted innervation of the epithelium in epithelialized polyps in some instances. The lesion may or may not bleed readily, depending upon the degree of vascularity of the tissue and epithelialization.

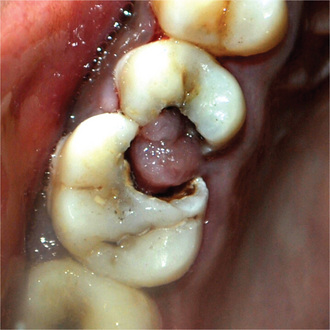

Figure 10-7 Chronic hyperplastic pulpitis.

(A) There is a mass of tissue protruding from the pulp chamber into the carious lesion. (B) In the photomicrograph this is seen to be continuous with the pulp and covered by stratified squamous epithelium (A, Courtesy of Dr S Karthigakannan, Department of Oral Medicine, Sree Moogambica Dental College, Tamil Nadu).

Histologic Features

The hyperplastic tissue is basically granulation tissue made up of delicate connective tissue fibers interspersed with variable numbers of small capillaries (Fig. 10-7). Inflammatory cell infiltration, chiefly lymphocytes and plasma cells, sometimes admixed with polymorphonuclear leukocytes, is common. In some instances fibroblast and endothelial cells proliferation is prominent.

This granulation tissue commonly becomes epithelialized and the origin of these epithelial cells is a matter of controversy. The epithelium is stratified squamous in type and closely resembles the oral mucosa, even to the extent of developing well formed rete ridges. The grafted epithelial cells are thought to be normally desquamated cells carried to the surface of the pulp by the saliva. Most desquamated epithelial cells in the saliva are degenerated superficial squames, which have lost their dividing capacity. For the polyp to become epithelialized, the cells should have the capacity to divide and differentiate into stratified squamous epithelium. So, such cells must come from the region of the basal cell layer and might be released from trauma or from the gingival sulcus. In some instances, the buccal mucosa may rub against the hyperplastic tissue mass, and epithelial cells become transplanted directly. Southam and Hodson have reported that polyps from deciduous teeth were epithelialized far more frequently (82% of 56 polyps) than those of permanent teeth (44% of 77 polyps). It should be appreciated that the tissue reaction here is an inflammatory hyperplasia and does not differ from inflammatory hyperplasia occurring elsewhere in the oral cavity as well as in other parts of the body. In time, organization of the tissue leads to decreased vascularity and increased fibrosis. M Sattari, AK Haghighi, and HD Tamijani showed that presence and concentration of IgE, histamine and IL-4 were higher in pulp polyps than in normal pulps, and suggested that type I hypersensitivity reaction being involved in pulp polyp’s pathogenesis.

Diseases of Periapical Tissues

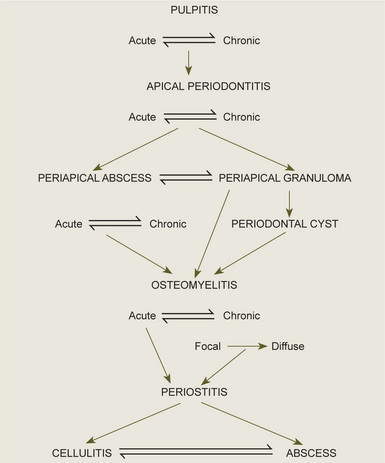

It is important to realize that these periapical lesions do not represent individual and distinct entities, but rather that there is a subtle transformation from one type of lesion into another type in most cases. Furthermore, it should be appreciated that a certain degree of reversibility is possible in some lesions. The interrelations between the types of periapical infection must be clearly understood, and the schematic diagram shown in Figure 10-9 will aid in clarification of this.

Acute Apical Periodontitis

Patients suffering from acute apical periodontitis usually give the history of previous pulpitis. Thermal change does not induce pain as in pulpitis. Due to the collection of inflammatory edema in the periodontal ligament, the tooth is slightly elevated in its socket and causes tenderness while biting or even to mere touch. The external pressure on the tooth forces the edema fluid against already sensitized nerve endings and results in severe pain. Radiographic appearance is essentially normal at this stage except for a slight widening of periodontal ligament space.

Chronic Apical Periodontitis

Chronic apical periodontitis, also known as periapical granuloma, is a low-grade infection and one of the most common of all sequelae of pulpitis or acute periapical periodontitis. If the acute process is left untreated, it is incompletely resolved and becomes chronic. The acute inflammatory process is an exudative response whereas the chronic one is proliferative. Periapical granuloma is essentially a localized mass of chronic granulation tissue formed in response to the infection (Fig. 10-10). But the use of this term is not totally accurate since it does not shows true granulomatous inflammation microscopically.

Figure 10-10 Periapical granuloma.

The granuloma often remains attached to the root when the tooth is extracted.

Radiographic Features

The earliest periapical change in the periodontal ligament appears as a thickening of the ligament at the root apex (Fig. 10-11). As proliferation of granulation tissue and concomitant resorption of bone continues, the periapical granuloma appears as a radiolucent area of variable size seemingly attached to the root apex (Fig. 10-12). In some cases, this radiolucency is a well-circumscribed, definitely demarcated from the surrounding bone. In these instances a thin radiopaque line representing a zone of sclerotic bone may sometimes be seen outlining the lesion. This indicates that the periapical lesion is a slowly progressive and long standing one that has probably not undergone an acute exacerbation.

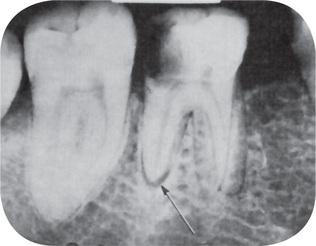

Figure 10-11 Early apical periodontitis.

There is radiographic evidence of thickening of the apical periodontal membrane as a result of the large carious lesion involving the dental pulp.

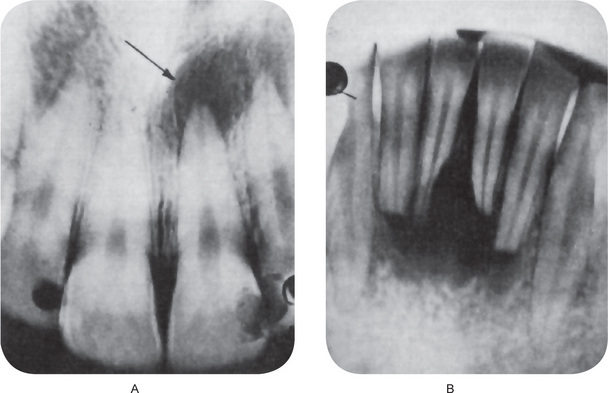

Figure 10-12 Periapical granuloma.

The periapical radiolucencies signify destruction of bone and replacement by granulation tissue. The maxillary central incisor (A) has a carious lesion of the distal surface that involves the pulp. The mandibular incisors (B) have sustained traumatic injury with loss of pulp vitality and subsequent formation of diffuse periapical granulomata.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Diseases of Dental Pulp

. Diseases of Dental Pulp . Classification of Pulpitis

. Classification of Pulpitis . Diseases of Periapical Tissues

. Diseases of Periapical Tissues . Osteomyelitis

. Osteomyelitis