Vesiculobullous Diseases

Viral Disease

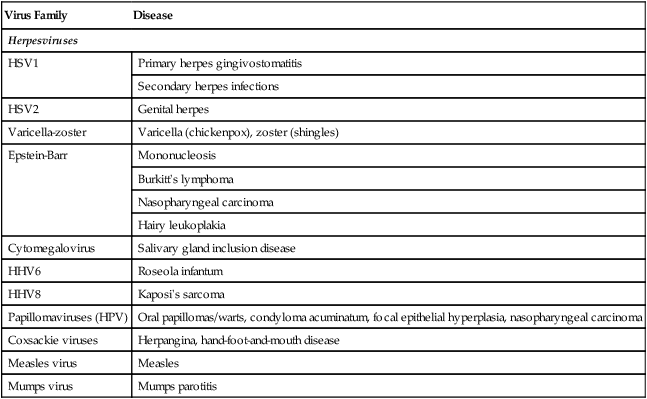

Oral mucous membranes may be infected by one of several different viruses, each producing a relatively distinct clinical pathologic picture (Table 1-1).

TABLE 1-1

| Virus Family | Disease |

| Herpesviruses | |

| HSV1 | Primary herpes gingivostomatitis |

| Secondary herpes infections | |

| HSV2 | Genital herpes |

| Varicella-zoster | Varicella (chickenpox), zoster (shingles) |

| Epstein-Barr | Mononucleosis |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | |

| Hairy leukoplakia | |

| Cytomegalovirus | Salivary gland inclusion disease |

| HHV6 | Roseola infantum |

| HHV8 | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Papillomaviruses (HPV) | Oral papillomas/warts, condyloma acuminatum, focal epithelial hyperplasia, nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| Coxsackie viruses | Herpangina, hand-foot-and-mouth disease |

| Measles virus | Measles |

| Mumps virus | Mumps parotitis |

Herpes Simplex Infection

Pathogenesis

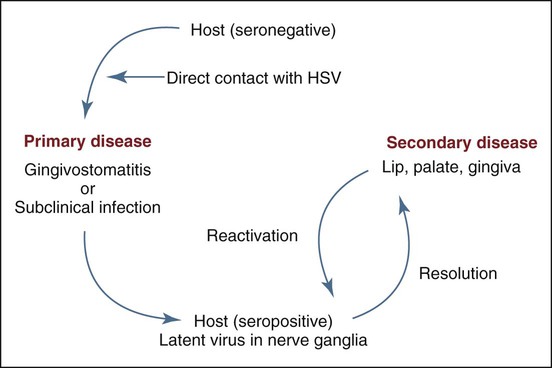

Physical contact with an infected individual or with body fluids is the typical route of HSV inoculation and transmission for a seronegative individual who has not been previously exposed to the virus, or possibly for someone with a low titer of protective antibody to HSV (Figure 1-1). The virus binds to the cell surface epithelium via heparan sulfate, which leads to transmembrane cytoplasmic insertion, followed by sequential activation of specific genes during the lytic phase of infection. These genes include immediate early (IE) and early (E) genes, coding for regulatory proteins and for DNA replication, and late (L) genes, coding for structural proteins. Documentation of the spread of infection through airborne droplets, contaminated water, or contact with inanimate objects is generally lacking. During the primary infection, only a small percentage of individuals show clinical signs and symptoms of infectious systemic disease, whereas a vast majority experience only subclinical disease. This latter group, now seropositive, can be identified through the laboratory detection of circulating antibodies to HSV.

Clinical Features

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

Primary disease is usually seen in children, although adults who have not been previously exposed to HSV or who fail to mount an appropriate response to a previous infection may be affected. By age 15, about half the population is infected. The vesicular eruption may appear on the skin, vermilion, and oral mucous membranes (Box 1-1 and Figure 1-2). Intraorally, lesions may appear on any mucosal surface. This is in contradistinction to the recurrent form of the disease, in which lesions are confined to the lips, hard palate, and gingiva. The primary lesions are accompanied by fever, arthralgia, malaise, anorexia, headache, and cervical lymphadenopathy.

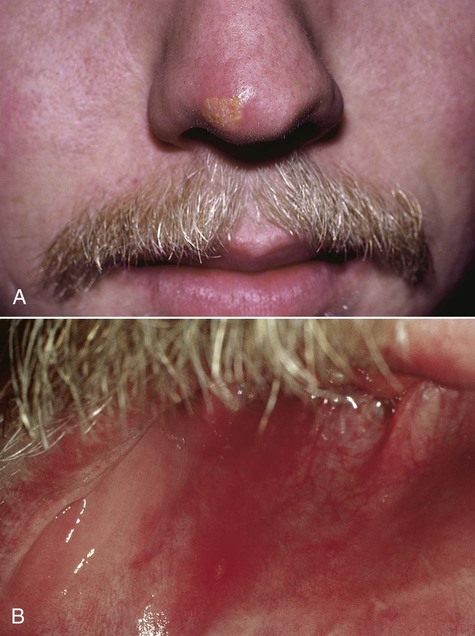

Secondary, or Recurrent, Herpes Simplex Infection

Patients usually have prodromal symptoms of tingling, burning, or pain in the site at which lesions will appear. Within a matter of hours, multiple fragile and short-lived vesicles appear. These become unroofed and coalesce to form maplike superficial ulcers. The lesions heal without scarring in 1 to 2 weeks and rarely become secondarily infected (Box 1-2; Figures 1-3 to 1-6). The number of recurrences is variable and ranges from one per year to as many as one per month. The recurrence rate appears to decline with age. Secondary lesions typically occur at or near the same site with each recurrence. Regionally, most secondary lesions appear on the vermilion and surrounding skin. This type of disease is usually referred to as herpes labialis. Intraoral recurrences are almost always restricted to the hard palate or gingiva.

Herpetic Whitlow

Herpetic whitlow is a primary or a secondary HSV infection involving the finger(s) (Figure 1-7). Before the universal use of examination gloves, this type of infection typically occurred in dental practitioners who had been in physical contact with infected individuals. In the case of a seronegative clinician, contact could result in a vesiculoulcerative eruption on the digit (rather than in the oral region), along with signs and symptoms of primary systemic disease. Recurrent lesions, if they occur, would be expected on the finger(s). Herpetic whitlow in a seropositive clinician (e.g., one with a history of HSV infection) is believed to be possible, although less likely because of previous immune stimulation by herpes simplex antigens.

Histopathology

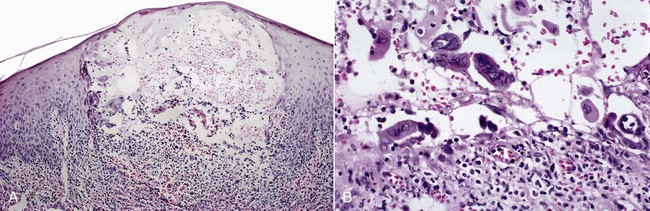

Microscopically, intraepithelial vesicles containing exudate, inflammatory cells, and characteristic virus-infected epithelial cells are seen (Figure 1-8). Virus-infected keratinocytes contain one or more homogeneous, glassy nuclear inclusions. These cells are also readily found on cytologic preparations. HSV1 cannot be differentiated from HSV2 histologically. After several days, herpes-infected keratinocytes cannot be demonstrated in biopsy or cytologic preparations. Herpes simplex lesions in HIV-positive patients may be coinfected with cytomegalovirus. The pathogenesis and significance of this phenomenon are undetermined.

Varicella-Zoster Infection

The overall incidence of varicella infection the United States has been substantially reduced of late by 76% to 87% as a result of widespread vaccination programs. Primary varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection in seronegative individuals is known as varicella or chickenpox; secondary or reactivated disease is known as herpes zoster or shingles (Box 1-3). Structurally, VZV is very similar to HSV, with a DNA core, a protein capsid, and a lipid envelope. Microscopically, striking similarities have been noted between herpes simplex conditions. A cutaneous or mucosal vesiculoulcerative eruption following reactivation of latent virus is typical of both VZV and HSV infections. Several signs and symptoms, however, appear to be unique to each infection.

Clinical Features

Varicella

Because of widespread vaccination, varicella is uncommon today in developed countries. Historically, a large majority of the population experienced primary infection during childhood. Fever, chills, malaise, and headache may accompany a rash that involves primarily the trunk and head and neck. The rash quickly develops into a vesicular eruption that becomes pustular and eventually ulcerates. Successive crops of new lesions appear, owing to repeated waves of viremia. This causes the presence, at any one time, of lesions at all stages of development (Figure 1-9). The infection is self-limiting and lasts several weeks. Oral mucous membranes may be involved in primary disease and usually demonstrate multiple shallow ulcers that are preceded by evanescent vesicles (Figure 1-10). Because of the intense pruritic nature of the skin lesions, secondary bacterial infection is not uncommon and may result in healing with scar formation. Complications, including pneumonitis, encephalitis, and inflammation of other organs, may occur in a very small percentage of cases. If varicella is acquired during pregnancy, fetal abnormalities may occur. When older adults and immunocompromised patients are affected, varicella may be much more severe and protracted, and more likely to produce complications.

Herpes Zoster

Zoster is essentially a condition of the older adult population and of individuals who have compromised immune responses. The incidence of herpes zoster infection increases with age, reaching approximately 10 cases per 100,000 patient-years by age 80.The sensory nerves of the trunk and head and neck are commonly affected. Involvement of various branches of the trigeminal nerve may result in unilateral oral, facial, or ocular lesions (Figures 1-11 and 1-12). Involvement of facial and auditory nerves produces the Ramsay Hunt syndrome, in which facial paralysis is accompanied by vesicles of the ipsilateral external ear, tinnitus, deafness, and vertigo.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses