CHAPTER 1 THE FUTURE NEED AND DEMAND FOR DENTAL IMPLANTS

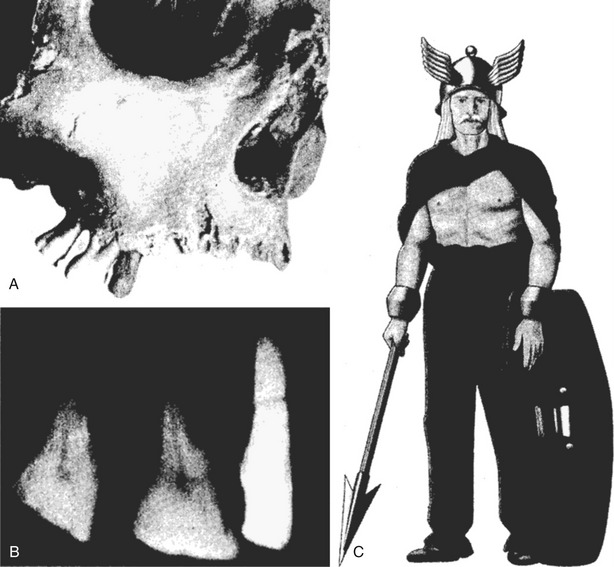

This chapter reviews the present and probable future need and demand for dental implants. A dental implant is defined as an artificial tooth root replacement and is used to support restorations that resemble a natural tooth or group of natural teeth (Figure 1-1).1

Figure 1-1. Comparison of natural tooth and crown with implant and crown.

(From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, 2004, The Dental Implant Center Press.)

Implants can be necessary when natural teeth are lost. When tooth loss occurs, masticatory function is diminished; when the underlying bone of the jaws is not under normal function it can slowly lose its mass and density, which can lead to fractures of the mandible and reduction of the vertical dimension of the middle face. Frequently, the physical appearance of the person is noticeably affected (Figure 1-2).1

Background

Background

Tooth Loss

Humans have lost their natural teeth throughout history. Teeth are lost for a variety of reasons.2–4 In primitive societies most teeth are lost as the result of trauma. Some are intentionally removed for sacred rituals or for cosmetic reasons (Figure 1-3).

In contrast to primitive societies, oral diseases and their sequelae have become the predominant cause of tooth loss in modern societies of the 20th and 21st centuries. Trauma still plays an important part in tooth loss, but less than that of oral diseases. A major reason for the increase in the role of disease in tooth loss in modern societies is the expanded proportion of refined sugar and other cariogenic food items that make up the diets of industrialized societies.5 This change in diet was a major contributing factor in an epidemic of dental caries during the first three quarters of the 20th century. The epidemic continued unabated until the deployment of modern preventive dentistry beginning around the middle of the 20th century.

Options for Replacement of Lost Teeth

When a tooth is lost, the individual and the dentist face two choices. The first choice is: should I replace the missing tooth? The second is: what is the best way to replace it? Although these decisions may seem sequential, they are interrelated in important ways. The technical options available can influence the decision to replace a tooth, and modern science has produced more and better options for tooth replacement in many circumstances.6–8 The age and general health of the patient are critical. The condition of the remaining dentition, its configuration in the mouth, and its periodontal support are very important aspects of the decision to replace.1,6 Finally, the relative cost of options can play a role, but should not be dispositive for a treatment plan. In making these decisions, the dentist and patient must evaluate all of these factors to reach the best treatment for a particular patient.5

Likewise, there are two basic options for replacing teeth in a completely edentulous arch:

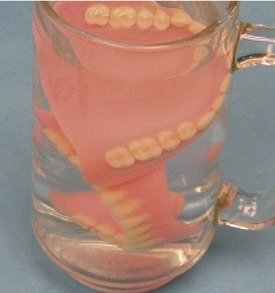

Figure 1-7. Many dentures become so unsatisfactory they are left in a glass of water.

(From Babbush CA: As good as new: a consumer’s guide to dental implants, Lyndhurst, OH, 2004, The Dental Implant Center Press.)

Tissue-Supported Prostheses: Partial and Complete Dentures

Removable dentures, whether partial or complete, are supported by the bone of the jaw and the soft oral mucosa covering the jaw.9,11 Removable partial dentures frequently are held in place by metal clasps that clip onto teeth or by precision attachments that insert into specially designed receptacles on artificial crowns placed on teeth adjacent to the space created by the missing tooth or teeth. Patients need to take these removable partial prostheses in and out regularly for cleaning after eating and at night.

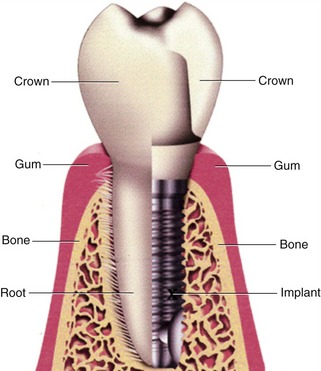

However, they have distinct problems for the individual who wears them. Tissue-supported prostheses continually stress the oral tissues.14 Over time, the weight-bearing stress caused by mastication—and to a lesser extent, other activities such as bruxism—can cause the underlying bone to resorb, reducing the bony mass of the jaws. If this bony resorption is extensive enough it can lead to fracture of the mandible. This bony pathology frequently is accompanied by local mucosal lesions created by the prosthesis. Sometimes the oral tissues cannot continue to support neither an existing tissue supported prosthesis nor a new prosthesis to replace the existing one (Figure 1-9).

Tooth-Supported Prostheses: Fixed Bridges

Tooth-supported fixed prostheses (bridges) rely on the adjacent teeth for support. The teeth next to the missing tooth space(s) are anatomically prepared to receive, in most cases, a porcelain, gold, or porcelain-fused-to-gold crown.10 After the teeth are prepared and a negative impression is taken, the fixed prosthesis is constructed by a dental laboratory. When the finished bridge is returned to the dentist, it is cemented onto the prepared abutment teeth. This prosthesis is fixed in place; it does not come in and out. It relies on the integrity of the adjacent teeth for support.

Bone-Supported Prostheses: Dental Implants

The final method of tooth replacement is the dental implant,8 which is a replacement for the root of a tooth. The implant is placed where the root of the missing tooth used to be. The replacement root is then used to attach a replacement tooth. Like the other options, dental implants are used to replace missing teeth and restore masticatory function to an individual’s dentition.

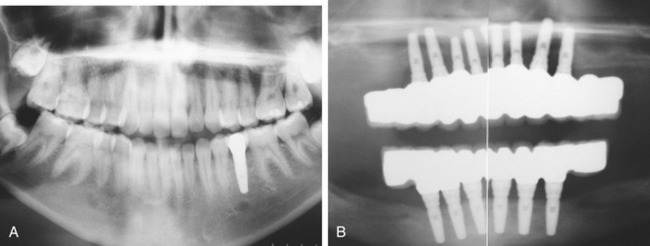

The major types of dental implants are osseointegrated and fibrointegrated implants.8 Earlier implants, such as the subperiosteal implant and the blade implant, were usually fibrointegrated. The most widely accepted and successful implant today is the osseointegrated implant. Examples of endosseous implants (implants embedded into bone) date back over 1350 years. While excavating Mayan burial sites in Honduras in 1931, archaeologists found a fragment of mandible with an endosseous implant of Mayan origin, dating from about 600 ad (Figure 1-10).

Figure 1-10. A Mayan lower jaw, dating from 600 ad, with three tooth implants carved from shells.

(From the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.)

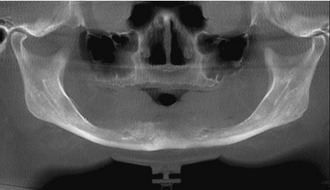

Widespread use of osseointegrated dental implants is more recent. Modern dental implantology developed out of the landmark studies of bone healing and regeneration conducted in the 1950s and 1960s by Swedish orthopedic surgeon P. I. Brånemark.15 This therapy is based on the discovery that titanium can be successfully fused with bone when osteoblasts grow on and into the rough surface of the implanted titanium. This forms a structural and functional connection between the living bone and the implant. A variation on the implant procedure is the implant-supported bridge, or implant-supported denture.

Today’s dental implants are strong, durable, and natural in appearance. They offer a long-term solution to tooth loss. Dental implants are among the most successful procedures in dentistry.16–20 Studies have shown a 5-year success rate of 95% for lower jaw implants and 90% for upper jaw implants. The success rate for upper jaw implants is slightly lower because the upper jaw (especially the posterior section) is less dense than the lower jaw, making successful implantation and osseointegration potentially more difficult to achieve. Lower posterior implantation has the highest success rate of all dental implants.

Additionally, dental implants may be used in conjunction with other restorative procedures for maximum effectiveness.21 For example, a single implant can serve to support a crown replacing a single missing tooth. Implants also can be used to support a dental bridge for the replacement of multiple missing teeth, and can be used with dentures to increase stability and reduce gum tissue irritation. Another strategy for implant placement within narrow spaces is the incorporation of the mini-implant. Mini-implants may be used for small teeth and incisors.

Modern dental implants are virtually indistinguishable from natural teeth. They are typically placed in a single sitting but require a period of osseointegration. This integration with the bone of the jaws takes anywhere from 3 to 6 months to anchor and heal.22,23 After that period of time a dentist places a permanent restoration for the missing crown of the tooth on the implant.

Although they demonstrate a very high success rate, dental implants may fail for a number of reasons, often related to a failure in the osseointegration process.24–30 For example, if the implant is placed in a poor position, osseointegration may not take place. Dental implants may break or become infected (like natural teeth) and crowns may become loose. Dental implants are not susceptible to caries attack, but poor oral hygiene can lead to the development of peri-implantitis around dental implants. This disease is tantamount to the development of periodontitis (severe gum disease) around a natural tooth.

Need and Demand for Tooth Replacement

Need and Demand for Tooth Replacement

Two general approaches are available to estimate the number of dental implants that will be placed.2,3 The first is a needs-based approach based on an estimation of unmet needs in a population. Workforce assessment starts with estimates of oral health personnel required to treat all oral disease or a specified proportion of that disease. A variation on this approach is to adjust those estimates downward based on the anticipated utilization of dental services by the populace.

The Concept and Measurement of Need

Need for care generally arises because of the existence of untreated disease. The scientific basis for efficacious therapy must also exist.2,3 Untreated disease in affluent societies usually coexists, with the majority of patients receiving the highest quality of care. In less affluent societies, a preponderance of disease may go without therapeutic intervention. The need-based approach uses normative judgments regarding the amount and kind of services required by an individual in order to attain or maintain some level of health. The level of unmet need in a society is usually determined from health level measurements based on epidemiological or other research identifying untreated dental disease. The underlying assumption is that those in need should receive appropriate care. Once the level of need is determined, the quantity of resources is then determined based on matching unmet need with appropriate care.

In addition, need assessment requires a normative judgment as to the amount and kind of services required by an individual to attain or maintain some level of health. Fundamentally, the need assessment focuses on which, and how many, services should be utilized. In almost all circumstances, this will differ from the services actually utilized. Oliver, Brown, and Löe31,32 provide a thorough discussion of dental treatment needs as well as a review of studies that estimate dental treatment needs.

The Concept and Measurement of Demand

In the United States, professionally trained dentists provide most dental services. These services are delivered through private markets shaped by supply and demand.2,3 Under a market system, dental services are provided to those who are willing and able to pay the dentist’s standard fee for the services rendered. This makes an assessment of demand for dental services essential for understanding the actual delivery of care. A clear distinction must be drawn between demand and unmet need for services in order to understand future access to care and what interventions are likely to be effective in altering access to care for some subpopulatio/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses