1 The Aging Face

Like all other theories or processes, surgeons and anatomists argue about what exactly happens during aging. Although most surgeons agree that atrophy, ligamentous laxity, and ptosis are causative factors, others argue against this. What is universally agreed upon is that aging is a gradual process of structural weakening, and its effects begin in the third decade and progress throughout an individual’s lifetime. Aging is basically a process of deflation, similar to the transition from grape to raisin (Figure 1-1).

FIGURE 1-1 The analogy of a grape transforming into a raisin symbolizes the loss of volume in facial aging.

The youthful face is tapered like an upside down egg, owing to the distinct volume and tight tissue retention (Figure 1-2, A). The aging face is more a reverse taper, similar to a right-side-up egg, due to the descent of volume and fat-compartment changes (Figure 1-2, B).

Aging changes are not only from volume loss and support changes but also intrinsic and extrinsic factors1–3 (Box 1-1). It is interesting that biological aging can sometimes exceed chronologic aging, and we all know 45-year-olds who look 60 (or the inverse).

Lifestyle and heredity are significant contributors to the aging equation. Some aging factors are controllable whereas others are not. Studies of monozygotic twins have revealed that aging is affected greatly by environmental and lifestyle factors, as measured by physical appearance. The factors that exert the greatest influence seem to be substance or alcohol abuse, sun exposure, and emotional distress.4 These aging changes are shown with supporting images in the various procedure chapters.

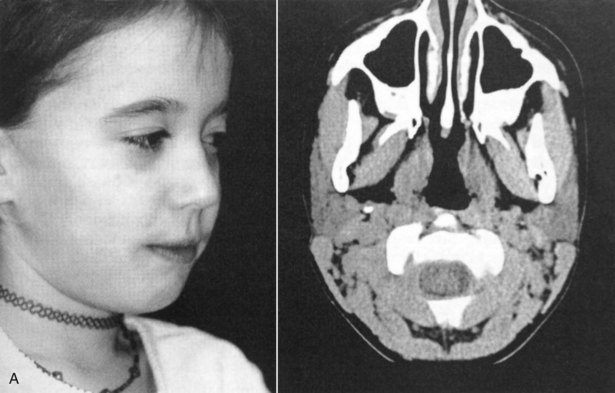

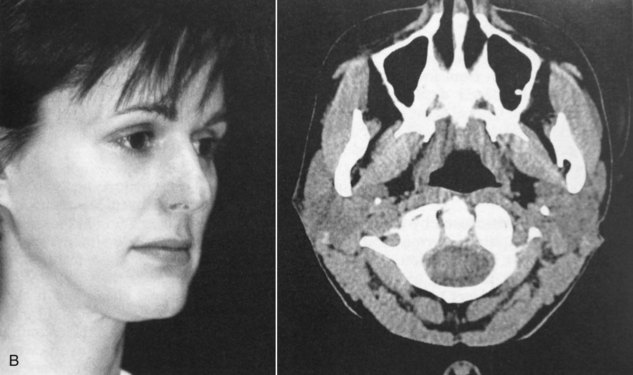

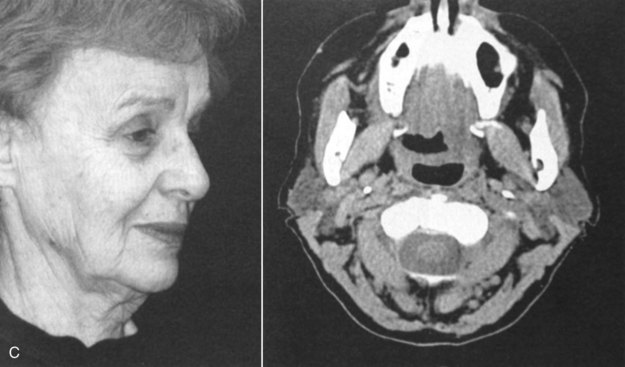

In the first clinic I wrote, Dr. Tom Faerber contributed a chapter on facial aging. To compare aging changes, he performed an interesting study in which he obtained computed tomography (CT) scans on his 9-year-old daughter, 42-year-old wife, and 75-year-old mother-in-law. These women’s ages were separated by roughly 35 years.5 Of particular note is that the youthful face is convex, whereas the aging face is concave due to fat atrophy, muscle atrophy, and gravitational and ptotic changes (Figure 1-3). A pattern of muscle atrophy was demonstrated in the masseter and buccinator muscles in the oldest family member. The parotid gland maintained its volume, but the surrounding perimuscular and subcutaneous fat showed atrophy. Fat and muscle atrophy in the temporal, buccal, and malar regions were also seen and contributed to the concavities in those regions that develop with age, as evidenced in the progressive CT scans.

Osseous volume-loss changes have also been implicated in midfacial aging.6,7 Other studies show osseous volume increases in the lower face.8

Regional Facial Aging

Skin

Photodamage describes aging changes of the skin from chronic ultraviolet (UV) light exposure. Cumulative photodamage can be seen in almost every patient by comparing the sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of skin (Figure 1-4). The most obvious clinical cutaneous aging changes include markedly increased skin roughness, increased mottled hyperpigmentation, increased loss of elasticity, increased wrinkling, and sallowness.

Genetic contributions to skin aging result in numerous biochemical, histologic, and physiologic changes: a reduction of vascularity, increased dermal/epidermal thickness, collagen changes, proteoglycan and dermal cellularity, and loss of elastic fibers.9–11

Photoaging causes functional and anatomic modifications in the exposed regions. Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation produces direct damage to the DNA of skin cells and also modulates the activity of cytokines and adhesion molecules.12,13 Ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation initiates the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which also damage nuclear and mitochondrial DNA and activate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).13

Histologically, the effects of skin photoaging include epidermal thickening, keratinocyte atypia, loss of polarity, and increased melanogenesis14 (Box 1-2). A fragmented and disorganized dermal fibrillar network is present and forms amorphous groups.15 Collagenous changes occur in the appearance of fragmented collagen fibrils, senescent fibroblasts, loss of function of glycosaminoglycans, and alterations in the cutaneous microvasculature.16

Contributing to exogenous skin aging is the decrease in skin functions that occur with age: decreases in cell replacement, injury response barrier function, sensory perception, immune and vascular responsiveness, thermoregulation, sweat production, sebum production, and vitamin D production.5

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses