CHAPTER 1 Examination of the Mouth and Other Relevant Structures

The plan should include recommendations designed to correct existing oral problems (or halt their progression) and to prevent anticipated future problems. It is essential to obtain all relevant patient and family information, to secure parental consent, and to perform a complete examination before embarking on this comprehensive oral health care program for the pediatric patient. Anticipatory guidance is the term often used to describe the discussion and implementation of such a plan with the patient and/or parents. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry has published guidelines concerning the periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, and oral treatment for children as summarized in Table 1-1.

INITIAL PARENTAL CONTACT WITH THE DENTAL OFFICE

The information recorded by the receptionist during this conversation constitutes the initial dental record for the patient. Filling out a patient information form is a convenient method of collecting the necessary initial information (see Fig. 29-3). Additional discussion of the initial communication with parents is presented in Chapter 29.

THE DIAGNOSTIC METHOD

Before making a diagnosis and developing a treatment plan, the dentist must collect and evaluate the facts associated with the patient’s or parents’ chief concern and any other identified problems that may be unknown to the patient or parents. Some pathognomonic signs may lead to an almost immediate diagnosis. For example, obvious gingival swelling and drainage may be associated with a single, badly carious primary molar. Although the collection and evaluation of these associated facts are performed rapidly, they provide a diagnosis only for a single problem area. On the other hand, a comprehensive diagnosis of all of the patient’s problems or potential problems may sometimes need to be postponed until more urgent conditions are resolved. For example, a patient with necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis or a newly fractured crown needs immediate treatment, but the treatment will likely be only palliative, and further diagnostic and treatment procedures will be required later.

The importance of thoroughly collecting and evaluating the facts concerning a patient’s condition cannot be overemphasized. A thorough examination of the pediatric dental patient includes assessment of:

Table 1-1 Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Oral Health Care

| Because each child is unique, these recommendations are designed for the care of children who have no contributing medical conditions and are developing normally. These recommendations will need to be modified for children with special health care needs or if disease or trauma manifests variations from normal. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) emphasizes the importance of very early professional intervention and the continuity of care based on the individualized needs of the child. Refer to the text of this guideline for supporting information and references. | |||||

| AGE | |||||

| 6–12 mo | 12–24 mo | 2–6 yr | 6–12 yr | 12+ yr | |

| Clinical oral examination1,2 | • | • | • | • | • |

| Assess oral growth and development3 | • | • | • | • | • |

| Caries-risk assessment4 | • | • | • | • | • |

| Radiographic assessment5 | • | • | • | • | • |

| Prophylaxis and topical fluoride4,5 | • | • | • | • | • |

| Fluoride supplementation6,7 | • | • | • | • | • |

| Anticipatory guidance counseling8 | • | • | • | • | • |

Additional diagnostic aids are often also required, such as radiographs, study models, photographs, pulp tests, and, infrequently, laboratory tests.1

In certain unusual cases, all of these diagnostic aids may be necessary to arrive at a comprehensive diagnosis. Certainly no oral diagnosis can be complete unless the diagnostician has evaluated the facts obtained by medical and dental history taking, inspection, palpation, exploration (if teeth are present), and often imaging (e.g., radiographs). For a more thorough review of evaluation of the dental patient, refer to the chapter by Glick, Greenberg, and Ship in Burket’s Oral Medicine.2

PRELIMINARY MEDICAL AND DENTAL HISTORY

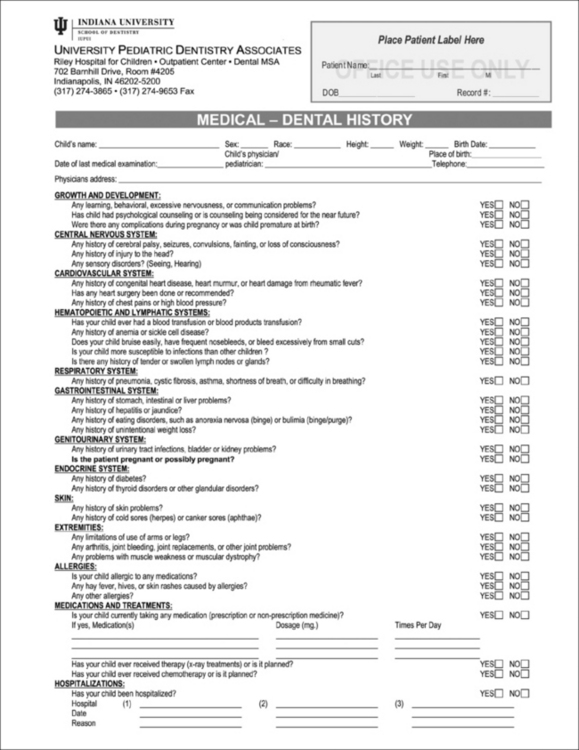

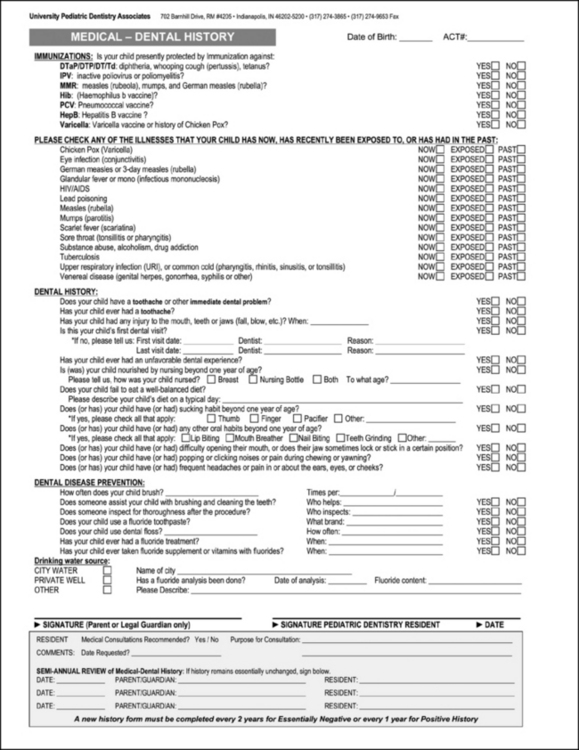

It is important for the dentist to be familiar with the medical and dental history of the pediatric patient. Familial history may also be relevant to the patient’s oral condition and may provide important diagnostic information in some hereditary disorders. Before the dentist examines the child, the dental assistant can obtain sufficient information to provide the dentist with knowledge of the child’s general health and can alert the dentist to the need for obtaining additional information from the parent or the child’s physician. The form illustrated in Fig. 1-1 can be completed by the parent. However, it is more effective for the dental assistant to ask the questions informally and then to present the findings to the dentist and offer personal observations and a summary of the case. The questions included on the form will also provide information about any previous dental treatment.

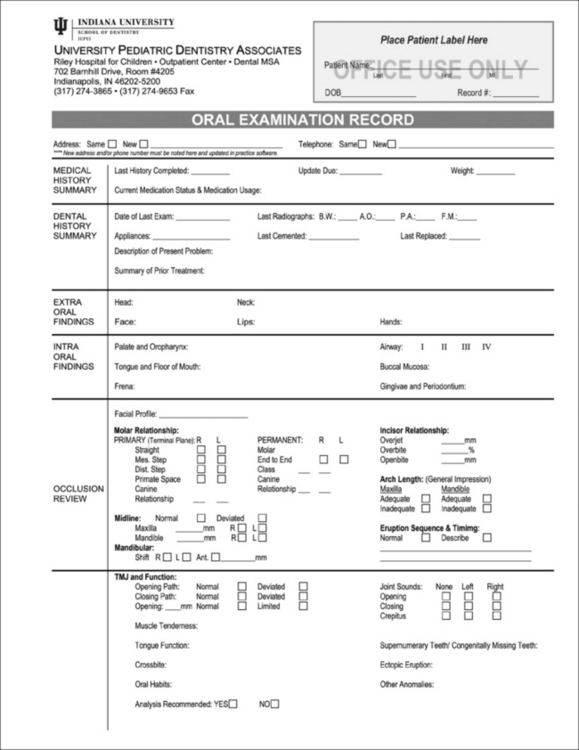

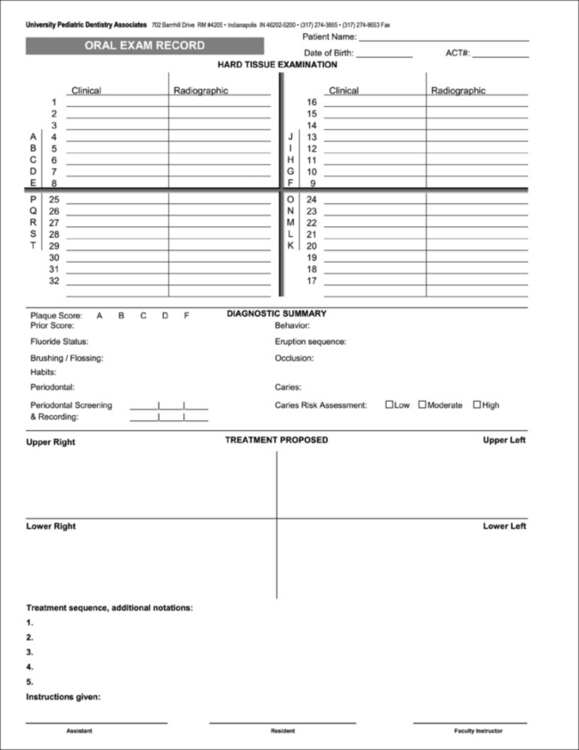

Figure 1-1 Form used in completing the preliminary medical and dental history.

(Printed with permission from Indiana University–University Pediatric Dentistry Associates.)

A notation should be made if a young child was hospitalized previously for general anesthetic and surgical procedures. Shaw reported that hospitalization and a general anesthetic procedure can be a traumatic psychological experience for a preschool child and may sensitize the youngster to procedures that will be encountered later in a dental office.3 If the dentist is aware that a child was previously hospitalized or the child fears strangers in clinic attire, the necessary time and procedures can be planned to help the child overcome the fear and accept dental treatment.

The dentist and the staff must also be alert to identify potentially communicable infectious conditions that threaten the health of the patient and others. Knowledge of the current recommended childhood immunization schedule is helpful. It is advisable to postpone nonemergency dental care for a patient exhibiting signs or symptoms of acute infectious disease until the patient recovers. Further discussions of management of dental patients with special medical, physical, or behavioral problems are presented in Chapters 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 14, Chapter 15, Chapter 23, Chapter 24, and Chapter 28.

The pertinent facts of the medical history can be transferred to the oral examination record (Fig. 1-2) for easy reference by the dentist. A brief summary of important medical information serves as a convenient reminder to the dentist and the staff, because they refer to this chart at each treatment visit.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

Most facts needed for a comprehensive oral diagnosis in the young patient are obtained by a thorough clinical and radiographic examination. In addition to examining the structures in the oral cavity, the dentist may in some cases wish to note the patient’s size, stature, gait, or involuntary movements. The first clue to malnutrition may come from observing a patient’s abnormal size or stature. Similarly, the severity of a child’s illness, even if oral in origin, may be recognized by observing a weak, unsteady gait of lethargy and malaise as the patient walks into the office. All relevant information should be noted on the oral examination record (see Fig. 1-2), which becomes a permanent part of the patient’s chart.

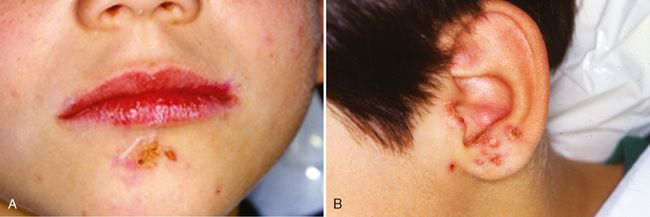

Inspection and palpation of the patient’s head and neck are also indicated. Unusual characteristics of the hair or skin should be noted. The dentist may observe signs of head lice (Fig. 1-3), ringworm (Fig. 1-4), or impetigo (Fig. 1-5) during the examination. Proper referral is indicated immediately, because these conditions are contagious. After the child’s physician has supervised the treatment to control the condition, the child’s dental appointment may be rescheduled. If a contagious condition is identified but the child also has a dental emergency, the dentist and the staff must take appropriate precautions to prevent spread of the disease to others while the emergency is alleviated. Further treatment should be postponed until the contagious condition is controlled.

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR EVALUATION

Okeson4 published a special report on temporomandibular disorders in children. Okeson indicated that, although several studies include children 5 to 7 years of age, most observations have been made in young adolescent. Studies have placed the findings into the categories of symptoms or signs—those reported by the child or parents and those identified by the dentist during the examination.

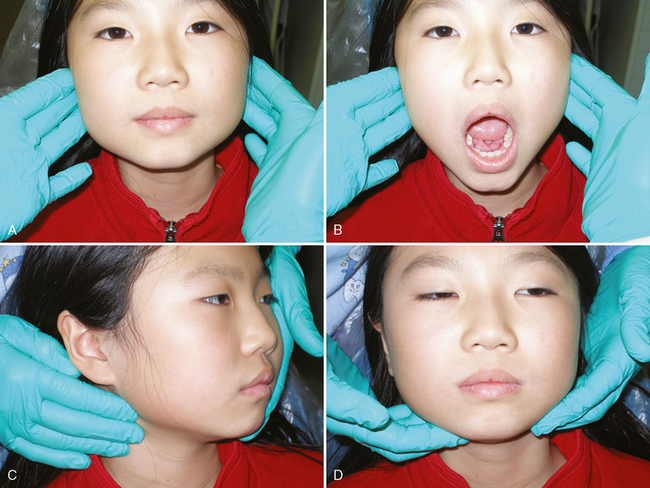

One should evaluate TMJ function by palpating the head of each mandibular condyle and observing the patient while the mouth is closed (teeth clenched), at rest, and in various open positions (Fig. 1-6A, B). Movements of the condyles or jaw that are not smoothly flowing or deviate from the expected norm should be noted. Similarly, any crepitus that may be heard or identified by palpation, or any other abnormal sounds, should be noted. Sore masticatory muscles may also signal TMJ dysfunction. Such deviations from normal TMJ function may require further evaluation and treatment. There is a consensus that temporomandibular disorders in children can be managed effectively by the following conservative and reversible therapies: patient education, mild physical therapy, behavioral therapy, medications, and occlusal splints.5

Discussion of the diagnosis and treatment of complex TMJ disorders is available from many sources; we suggest Okeson’s Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion (2008).6

The extraoral examination continues with palpation of the patient’s neck and submandibular area (see Fig. 1-6C, D). Again, deviations from normal, such as unusual tenderness or enlargement, should be noted and follow-up tests performed or referrals made as indicated.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses