Evidence-based practice

1.1 Decision making

Evidence-based medicine

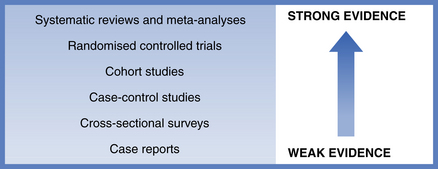

Best research evidence is clinically relevant research from basic science and clinical research. It either validates previously accepted diagnostic tests, preventive regimens and treatments, or replaces them with new ones that are more powerful, more accurate, more effective and safer. The strength of evidence from various study designs is shown in Fig. 1.1.

Benefits and limitations of evidence-based medicine

The randomised controlled trial provides the underlying basis for evidence-based medicine and the number of trials is growing exponentially with more than 150 000 listed by the Cochrane Library. However, there are limitations to evidence-based medicine. There is a shortage of consistent scientific evidence, difficulties in application of research evidence to individual patients and barriers to the practice of high-quality care. Some clinicians misunderstand the philosophy of evidence-based medicine and incorrectly believe that it means a loss of clinical freedom, or that it ignores the importance of clinical experience and of individual values, which is not the case.

1.2 Randomised controlled trials

Randomised controlled trials may be used to compare health screening, diagnostic and preventative strategies, in addition to different treatments. They are recognised as one of the simplest, yet most powerful and revolutionary clinical research tools that we have. People are allocated at random to receive one of several clinical interventions, and comparisons are made (Fig. 1.2).

Components of the randomised controlled trial

• The patients who take part in the trial are referred to as ‘participants’ or the study population. Participants don’t have to be ill as the study can be conducted in healthy volunteers or members of the general public.

• The investigators are those that design the study, administer the interventions and analyse the results.

• One of the interventions is usually regarded as the standard of comparison or ‘control’, hence the name randomised controlled trial. The group of participants who receive the control are known as the ‘control group’. The control may be conventional treatment, placebo or no treatment.

• Outcomes are measures, so randomised controlled trials are regarded as quantitative studies. They compare two or more interventions and so are regarded as comparative studies. Case-series studies may also be quantitative but do not include comparisons among groups.

Randomisation and allocation concealment

The best method for allocation to study group is to use random-number tables or computer-generated sequences. Some investigators report using ‘odd or even’ birth year or hospital number but there may be problems with these ‘quasi-randomisation’ methods. The investigator may subvert the allocation because he or she knows which group the patient will be in and the study results could be biased as the groups are not properly balanced. For example, if comparing different surgical techniques for the removal of wisdom teeth, it would be important to have an equal mix of simple and difficult cases in the different groups and not all the simple cases in one group and all the difficult cases in another. If the groups are kept as similar as possible at the start of the study then it will be easier to isolate and quantify the impact of the intervention.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses