Today’s dentist does not just repair teeth to make them better for chewing. Increasingly, his or her work involves esthetics. With patients demanding more attractive teeth, dentists now must become more familiar with the formerly independent disciplines of orthodontics, periodontics, restorative dentistry, and maxillofacial surgery. This article provides a systematic method of evaluating dentofacial esthetics in a logical, interdisciplinary manner. In today’s interdisciplinary dental world, treatment planning must begin with well-defined esthetic objectives. By beginning with esthetics, and taking into consideration the impact on function, structure, and biology, the clinician will be able to use the various disciplines in dentistry to deliver the highest level of dental care to each patient.

In the past 25 years, the focus in dentistry has gradually changed. Years ago, dentists were in the repair business. Routine dental treatment involved excavating dental caries and filling of the enamel and dentinal defects with amalgam. In larger holes, more durable restorations may have been necessary, but the focus was the same: repair the effects of dental decay. However, with the advent of fluorides and sealants, in addition to the emergence of a better understanding of bacteria’s role in causing both caries and periodontal disease, the needs of the dental patient have gradually changed. Many young adults who are products of the sealant generation have little or no decay and few existing restorations. At the same time, our image of the value of teeth in Western society has also changed. Yes, the public still regards teeth as an important part of chewing, but today the focus of many adults has shifted toward esthetics. How can my teeth be made to look better? Therefore, the formerly independent disciplines of orthodontics, periodontics, restorative dentistry, and maxillofacial surgery must often join together to satisfy the public’s desire to look better.

This trend toward a heightened awareness of esthetics has challenged dentistry to look at dental esthetics in a more organized and systematic manner, so that the health of patients and their teeth is still the most important underlying objective. But some existing dentitions simply cannot be restored to a more pleasing appearance without the assistance of several different dental disciplines. Today, every dental practitioner must have a thorough understanding of the roles of these various disciplines in producing an esthetic makeover, with the most conservative and biologically sound interdisciplinary treatment plan possible. The authors have worked in such an environment for the past 20 years. As prosthodontist and orthodontist, we have belonged to an interdisciplinary study group consisting of nine dental specialists and one general dentist since 1984 . We have met monthly since that time to (1) educate one another about the advances in each of our respective areas of dentistry and (2) to plan interdisciplinary treatment for some of the most challenging and complex dental situations. One of these interdisciplinary areas is esthetics. This article provides a systematic method of evaluating dentofacial esthetics in a logical, interdisciplinary manner.

Sequencing the planning process

Historically, the treatment planning process in dentistry usually began with an assessment of the biology or biological aspects of a patient’s dental problem. This could include the patient’s caries susceptibility, periodontal health, endodontic needs, and general oral health. Once the biologic health was reestablished either through caries removal, modification of the bone or gingiva, endodontic therapy, or tooth removal, then the restoration of the resulting defects would be based upon structural considerations. If teeth were to be restored or repositioned, the function of the teeth and condyles would be of paramount importance in dictating occlusal form and occlusal relationships, respectively. Finally, esthetics would be addressed to provide a pleasing appearance of the teeth. However, if the treatment planning sequence proceeds from biology to structure to function and finally to esthetics, the eventual esthetic outcome may be compromised. We proceed in the opposite direction. That is, we start the treatment planning process with esthetics and proceed to function, structure, and finally biology. We do not leave out any of the important parameters; we simply sequence the planning process from a different perspective. We choose this sequence because the decisions made in each category, especially esthetics, directly affect the following categories.

Beginning with esthetics in mind

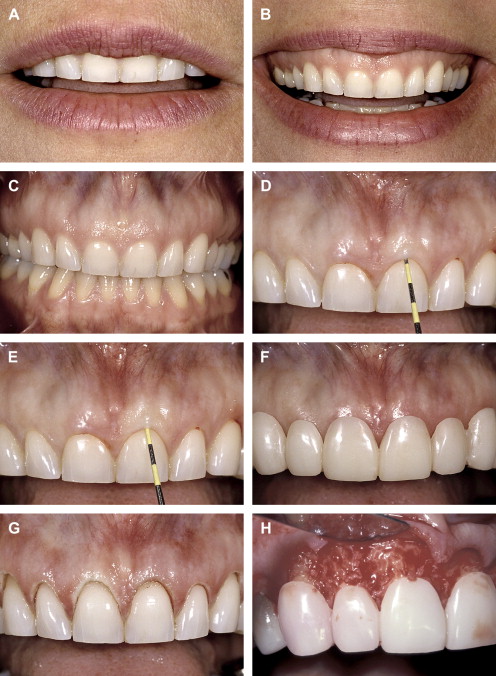

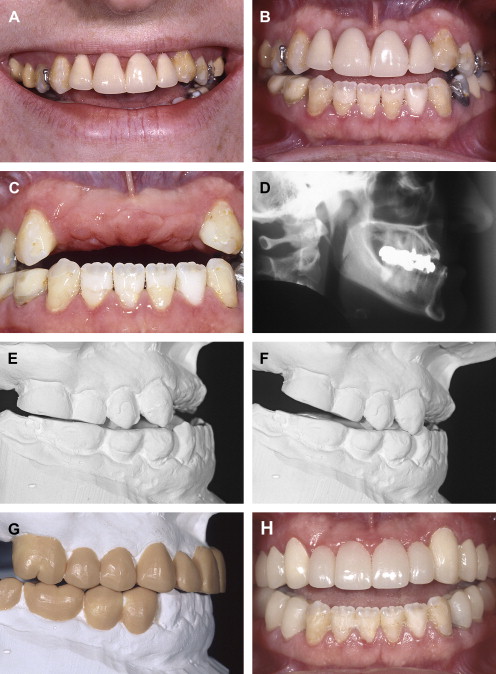

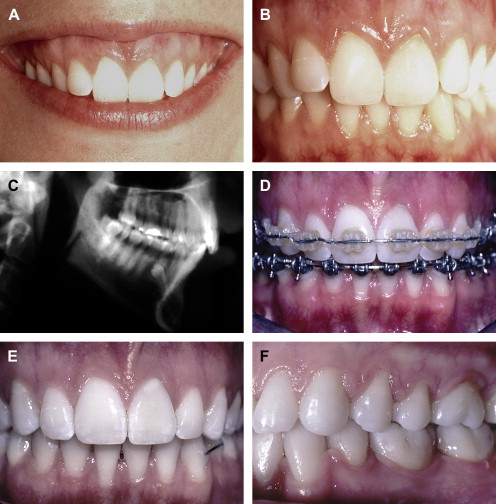

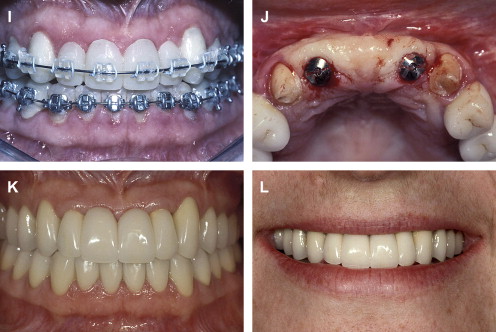

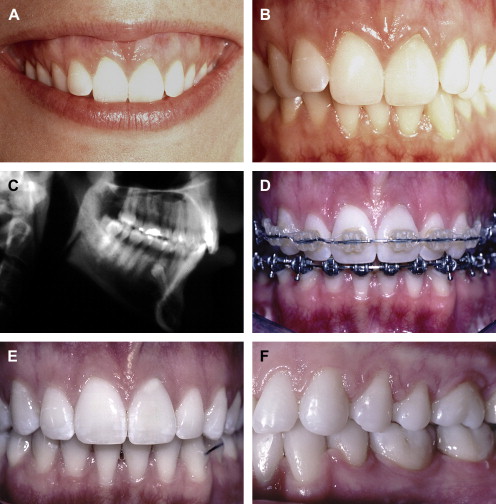

When beginning with esthetics, we must begin with an appraisal of the position of the maxillary central incisors relative to the upper lip ( Fig. 1 ). This assessment is made with the patient’s upper lip at rest. Using a millimeter ruler or a periodontal probe, we determine the position of the incisal edge of the maxillary central incisor relative to the upper lip. The position of the maxillary central incisor can either be acceptable or unacceptable. An acceptable amount of incisal edge display at rest depends on the patient’s age. Previous studies have shown that with advancing age, the amount of incisal display decreases proportionally . For example, in a 30-year-old, 3 mm of incisal display at rest is appropriate. However, in a 60-year-old, the incisal display could be 1 mm or less. The change in incisal display with time probably relates to the resiliency and tone of the upper lip, which tends to decrease with advancing age.

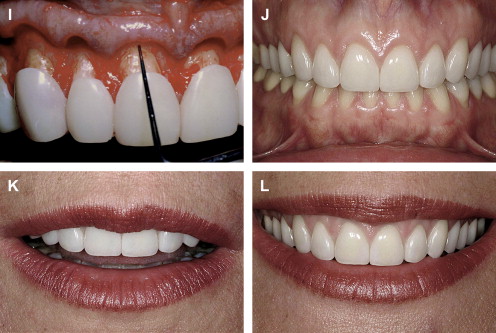

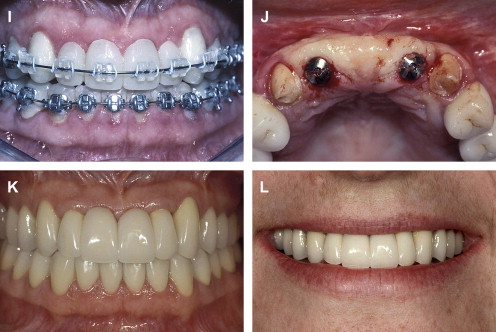

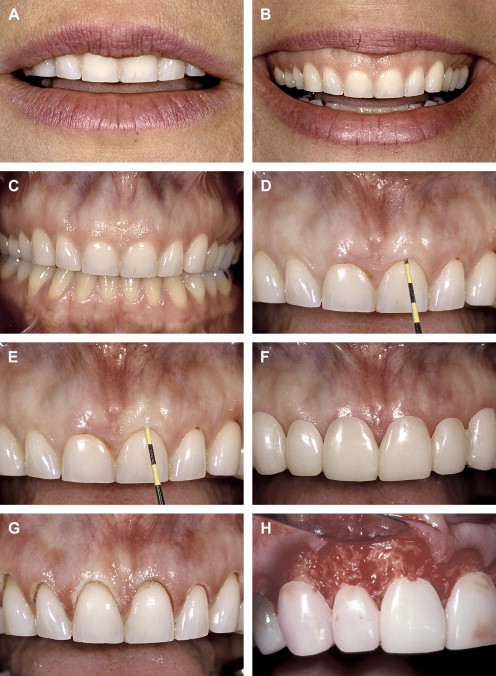

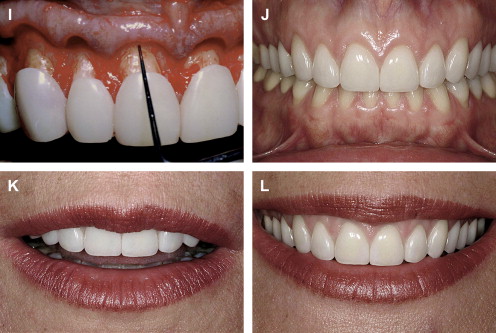

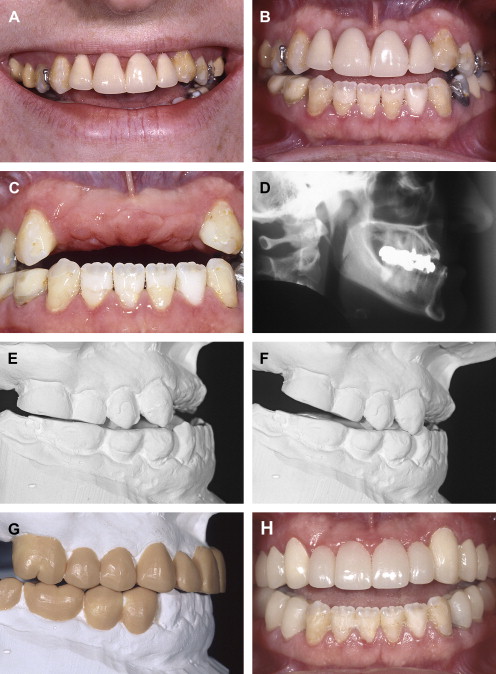

If the incisal edge display is inadequate ( Fig. 2 ), then a primary objective of interdisciplinary treatment may be to lengthen the maxillary incisal edges. This objective could be accomplished with restorative dentistry , orthodontic extrusion , or orthognathic surgery . Choosing the correct procedure depends upon the patient’s facial proportions, existing crown length, and opposing occlusion. If the incisal edge display is excessive ( Fig. 3 ), then an objective of treatment could be to move the maxillary incisors apically either by equilibration , restoration , orthodontics , or orthognathic surgery . The selection among these disciplines again depends on the patient’s existing anterior occlusion, the patient’s facial proportions, or both.

The second aspect of esthetic tooth positioning to be evaluated is the maxillary dental midline. Recent studies have shown that lay people do not notice midline deviations to the right or left of up to 3 or 4 mm if the long axes of the teeth are parallel with the long axis of the face . So, perhaps the most important relationship to evaluate is the medio-lateral inclination of the maxillary central incisors. If the incisors are inclined by 2 mm to the right or left, lay people regard this discrepancy as unesthetic . A canted midline can be corrected with orthodontics or restorative dentistry . Usually the choice depends upon whether the maxillary incisors will require restoration.

Beginning with esthetics in mind

When beginning with esthetics, we must begin with an appraisal of the position of the maxillary central incisors relative to the upper lip ( Fig. 1 ). This assessment is made with the patient’s upper lip at rest. Using a millimeter ruler or a periodontal probe, we determine the position of the incisal edge of the maxillary central incisor relative to the upper lip. The position of the maxillary central incisor can either be acceptable or unacceptable. An acceptable amount of incisal edge display at rest depends on the patient’s age. Previous studies have shown that with advancing age, the amount of incisal display decreases proportionally . For example, in a 30-year-old, 3 mm of incisal display at rest is appropriate. However, in a 60-year-old, the incisal display could be 1 mm or less. The change in incisal display with time probably relates to the resiliency and tone of the upper lip, which tends to decrease with advancing age.

If the incisal edge display is inadequate ( Fig. 2 ), then a primary objective of interdisciplinary treatment may be to lengthen the maxillary incisal edges. This objective could be accomplished with restorative dentistry , orthodontic extrusion , or orthognathic surgery . Choosing the correct procedure depends upon the patient’s facial proportions, existing crown length, and opposing occlusion. If the incisal edge display is excessive ( Fig. 3 ), then an objective of treatment could be to move the maxillary incisors apically either by equilibration , restoration , orthodontics , or orthognathic surgery . The selection among these disciplines again depends on the patient’s existing anterior occlusion, the patient’s facial proportions, or both.

The second aspect of esthetic tooth positioning to be evaluated is the maxillary dental midline. Recent studies have shown that lay people do not notice midline deviations to the right or left of up to 3 or 4 mm if the long axes of the teeth are parallel with the long axis of the face . So, perhaps the most important relationship to evaluate is the medio-lateral inclination of the maxillary central incisors. If the incisors are inclined by 2 mm to the right or left, lay people regard this discrepancy as unesthetic . A canted midline can be corrected with orthodontics or restorative dentistry . Usually the choice depends upon whether the maxillary incisors will require restoration.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses