Chapter 8

The Detailed Clinical Periodontal Examination

Aim

The purpose of this chapter is to outline the key stages involved in examining in detail patients identified as being susceptible to periodontitis.

Outcome

It is anticipated that having read this section, practitioners will understand the rationale for the individual measures recommended, and that they will be in a position to perform, record and interpret such assessments and produce appropriate treatment plans.

The Clinical Periodontal Examination

Having completed the extra-oral, general intra-oral and periodontal screening examinations, it should be apparent whether a detailed periodontal examination is necessary. If so, this will inevitably take a significant amount of time, but there are unfortunately no current alternatives. All sites to undergo a detailed examination need to be very carefully observed owing to the site-specific nature of the disease (see Chapter 5). No assumptions can be made about the mouth as a whole from a limited examination of only a few sites.

The detailed clinical examination comprises five separate parts and always precedes any radiological examination or other special tests. The information gained from this allows the clinician to decide on a logical basis whether additional tests are required and if so which ones. This ensures that only necessary tests are prescribed. The five components are:

-

presence/absence of BOP

-

PPD

-

LOA

-

furcation involvement

-

mobility.

Lack of Bleeding on Probing from the Base of the Pocket

The first thing to be examined is whether there is or is not bleeding on probing from the base of the pockets.

Why?

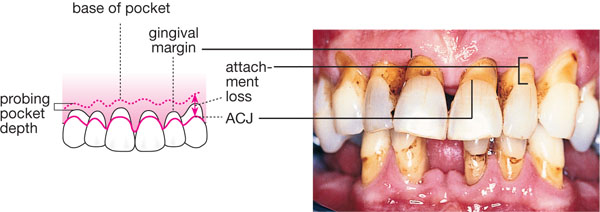

Bleeding on probing from the base of the pocket is still regarded as the best individual clinical indicator of disease activity (Fig 8-1). Historically, BOP from the base of the pocket was thought to indicate the presence of active disease at that site at that time. Indeed this mantra recognised the concept of site specificity while acknowledging that disease is often episodic in nature. However, in the early 1990s, research demonstrated that only a maximum of 30% of sites exhibiting BOP from the base of pockets went on to lose attachment. It is thus more acceptable now to talk about lack of bleeding on probing from the base of the pocket, since we know that almost 100% of such sites in non-smokers will not progress to attachment loss. Whilst a lack of bleeding from the base of the pocket is associated with a lack of disease activity, the studies that demonstrated this did not take smoking habit into account. The absence of BOP from individual sites in current smokers cannot therefore be included in these interpretations.

Fig 8-1 Photograph illustrating bleeding on probing from the base of the pocket.

How?

The assessment of BOP must be approached in a systematic manner ensuring that all sites are examined. It is thus important to get into a routine of performing this test in the same way each time, e.g. checking all buccal surfaces of the lower arch starting at, say, the lower left 7, progressing round the arch and then doing the equivalent for the upper arch. Once completed, this is repeated for the lingual/palatal surfaces. The examination is best accomplished by running a periodontal probe gently along the bases of appropriate gingival sulci and then checking to see whether bleeding occurs.

It is important to keep the probe tip moving as applying point pressure may result in false positive results due to localised soft tissue penetration. Although any bleeding induced will be noticed at the gingival margin, it is essential that it is the tissues at the base of the pocket/gingival sulci that are tested. Sometimes the bleeding is immediate and profuse, while at other times it is delayed and scanty. It is suggested, therefore, that once a buccal or lingual quadrant has been completed, the clinician looks back along the quadrant sites tested so that delayed bleeding may be detected. The amount of bleeding produced is much less important than whether or not it occurs at all. It is because of this that many examiners choose to record BOP from sites qualitatively as being either present or absent. Although this may initially appear to be undervaluing detailed information, it does remove the problems of individual interpretation of more complex indices and the associated time involved.

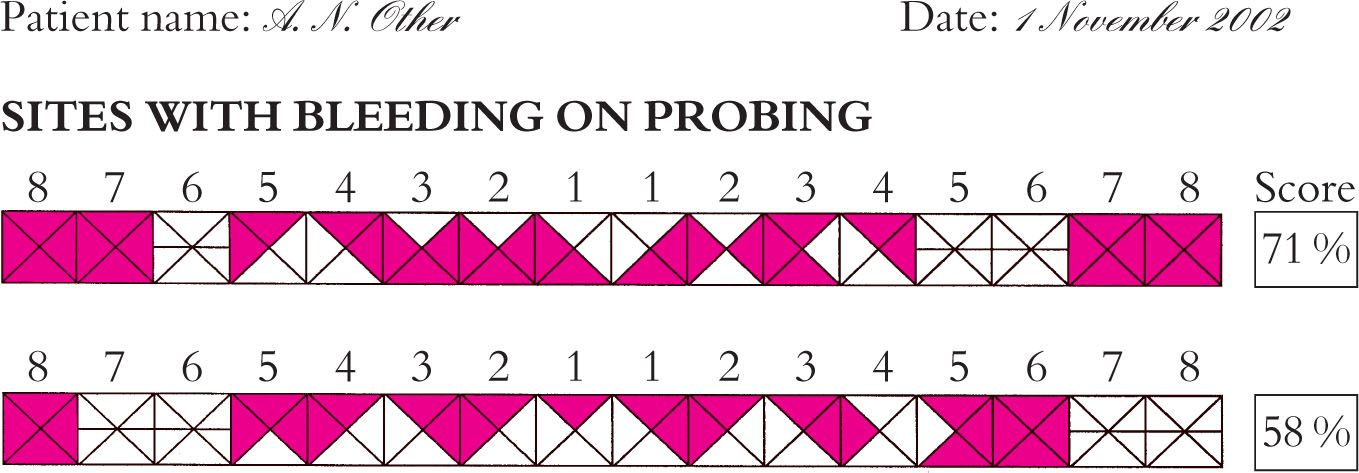

Recording the Information

This may be done in a variety of ways, but perhaps the most succinct is via the type of chart shown in Fig 8-2. First, all missing teeth are deleted (illustrated by placing a horizontal line through the box representing the tooth) and those present are divided into 4 surfaces – buccal, lingual, mesial and distal. Presence or absence of BOP from the base of the pockets at each site is then noted and the appropiate segments coloured in – conventionally in red. Once completed, this format allows easy calculation of the percentage of sites affected and also allows pictorial representation of their distribution. This information is useful for both treatment planning at the beginning of therapy and at the re-evaluation phase, as well as being useful in patient motivation.

Fig 8-2 Photograph showing a completed bleeding chart.

Probing Pocket Depth (PPD)

Measurement of PPDs at as many sites as possible around the mouth is essential. Multiple site measurement is mandatory owing to the variation in periodontal disease experience seen within and between mouths.

Why?

In basic terms, if a pocket is ≤3mm, patients can keep the site clean using normal home-care methods. If pockets are deeper than this, patients cannot adequately clean them, resulting in an increased risk of continued destruction. One simple aim of periodontal therapy may therefore be regarded as reducing all PPDs to ≤3mm.

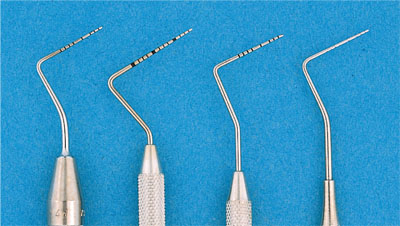

How?

PPD is the measurement from the gingival margin to the base of the pocket, when assessed by clinical probing (Chapter 1). It is measured using any one of a number of different periodontal probes (Fig 8-3) which all share the characteristics of having a blunt end to reduce the risk of tissue penetration and a series of markings along their length to facilitate the measurement process.

Fig 8-3 Photograph illustrating several types of periodontal probe.

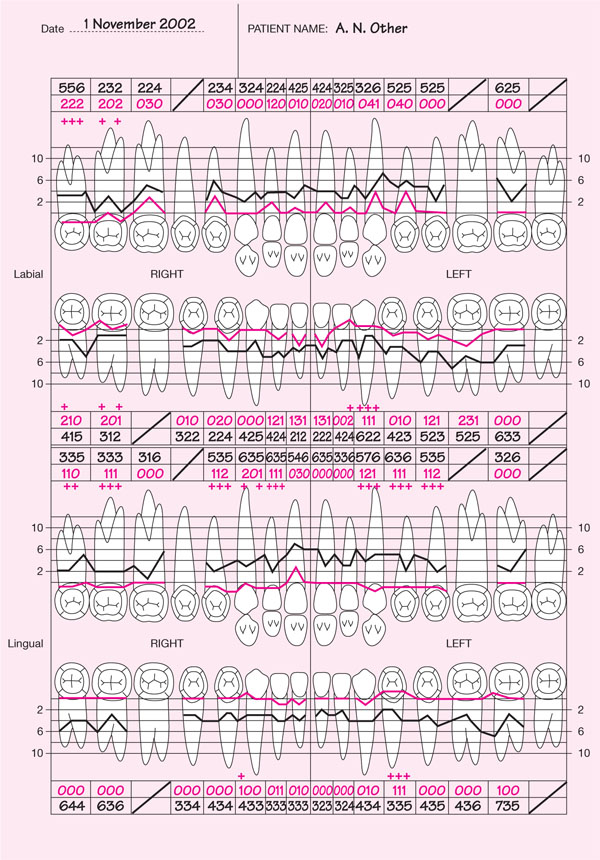

Recording the information

Some experienced clinicians find it quicker to record PPDs sequentially as buccal maxillary left quadrant, followed by palatal maxillary left quadrant, etc., and to circle sites that bleed on probing in red pen and sites of suppuration in blue/black pen. This clearly also provides six-sites-per-tooth assessment of BOP, but assumes the correct probing pressure has been used for bleeding scores. Whichever system is used depends on personal clinical preference. Should the clinician wish to have detailed records, a “double periodontal chart” such as that shown in Fig 8-4 is helpful. Specific details of how to complete this type of pocket chart are given later in this chapter.

Fig 8-4 Completed “double periodontal chart”.

LOA

Measurement of LOA at as many sites as possible around the mouth is important.

Why?

LOA is a measure of the sum total of periodontal destruction experienced at a particular site since the tooth erupted. It does not, however, provide information about the number of episodes of disease that have taken place or when they occurred. In terms of examination, diagnosis and treatment planning, it should be regarded as the background upon which the current detail of pocket depth should be placed.

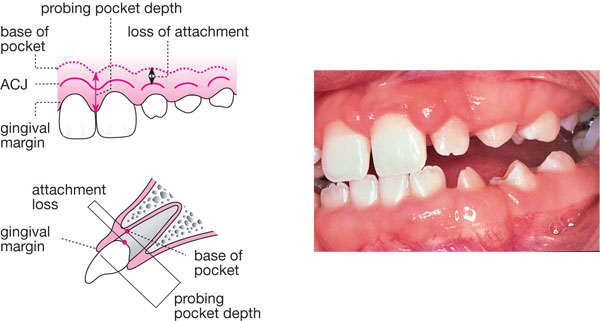

How?

LOA is the measurement from the amelo-cemental junction (ACJ) to the base of the pocket.

Significance?

Usually pocket depth and LOA are different – only if the gingival margin lies at the ACJ will they be the same. In sites with gingival enlargement (Fig 8-5) pocket depth will exceed LOA and reliance upon pocket depth alone as an indicator of past disease experience will lead to over-estimation. The opposite is true in sites exhibiting recession/shrinkage (Fig 8-6), where using pocket depth alone would lead the observer to under-estimate disease experience.

Fig 8-5 Photograph of gingival enlargement and diagram to show how both LOA and PPD would be measured. In this case, the PPD is greater than the LOA.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses