Salivary Gland Diseases

Reactive Lesions

Mucus Extravasation Phenomenon

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The cause of mucus extravasation phenomenon is traumatic severance of a salivary gland excretory duct, resulting in escape of mucus, or extravasation, into the surrounding connective tissue (Figure 8-1). An inflammatory reaction of neutrophils followed by macrophages ensues. Granulation tissue forms a wall around the mucin pool, and the contributing salivary gland undergoes inflammatory change. Ultimately, scarring occurs in and around the gland.

Clinical Features

The lower lip is the most common site of mucus extravasation phenomenon, but the buccal mucosa, anterior-ventral surface of the tongue (location of Blandin-Nuhn glands), floor of the mouth, and retromolar region are often affected (Figures 8-2 and 8-3). Lesions are uncommonly found in other intraoral regions where salivary glands are located, probably because of lower susceptibility to trauma.

Histopathology

Extravasation of free mucin incites an inflammatory response that is followed by connective tissue repair. Neutrophils and macrophages are seen, and granulation tissue forms around the mucin pool (Figure 8-4). The adjacent salivary gland whose duct was transected shows ductal dilation, chronic inflammation, acinar degeneration, and interstitial fibrosis.

Mucus Retention Cyst (Obstructive Sialadenitis)

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Mucus retention cysts usually result from obstruction of salivary flow caused by a sialolith (Box 8-1). The sialolith(s) may be found anywhere in the ductal system, from the gland parenchyma to the excretory duct orifice. A sialolith represents the precipitation of calcium salts (predominantly calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate) around a central nidus of cellular debris, inspissated mucin, and/or bacteria. Predisposition includes salivary stasis, chronic sialadenitis, and gout (uric acid calculi). Occasionally, periductal scar or an impinging tumor may cause the obstructive sialadenitis.

Histopathology

The cystlike cavity of a mucus retention cyst is lined by normal but compressed ductal epithelium (Figure 8-7). The type of lining formed by the epithelial cells ranges from pseudostratified to stratified squamous. The cystlike lumen contains mucin obstructed by a sialolith. The connective tissue around the lesion is minimally inflamed, although the associated gland shows inflammatory-obstructive change.

Maxillary Sinus Retention Cyst/Pseudocyst

Clinical Features

A great majority of these lesions are asymptomatic, although some slight tenderness may be noted in the mucobuccal fold or, more rarely, palpable buccal expansion in this region. On panoramic and periapical radiographs, retention cysts and pseudocysts of the maxillary sinus are hemispheric, homogeneously opaque, and well delineated (Figure 8-8). They usually demonstrate an attachment to the floor of the antrum, with size—rather than duration—being a function of the anatomic space. Uncommonly, these lesions may appear bilaterally.

Necrotizing Sialometaplasia

Necrotizing sialometaplasia is a benign condition that typically affects the palate and rarely other sites containing salivary glands (Box 8-2). Recognition of this entity is important because it mimics malignancy both clinically and microscopically. Unnecessary surgery has been performed because of an erroneous preoperative diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma or mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Clinical Features

Intraorally, necrotizing sialometaplasia is characterized by a seemingly spontaneous appearance, most commonly at the junction of the hard and soft palates (Figure 8-9). Early in its evolution, the lesion may be noted as a tender swelling, often with a dusky erythema of the overlying mucosa. Subsequently the mucosa breaks down, and a sharply demarcated deep ulcer with a yellowish gray lobular base is formed. In the palate, the lesion may be unilateral or bilateral, with individual lesions ranging from 1 to 3 cm in diameter. Pain is generally disproportionately slight compared with the size of the lesion. Healing is generally protracted, taking from 6 to 10 weeks.

Histopathology

Submucosa adjacent to an ulcer shows necrosis of salivary glands and squamous metaplasia of salivary duct epithelium (Figure 8-10). Preservation of the lobular architecture of salivary glands serves to distinguish this process from neoplasia. The characteristic ductal squamous metaplasia shows no cytologic atypia, but the pattern may be misinterpreted as squamous cell carcinoma. When this metaplasia is seen in the presence of residual viable salivary gland, the lesion may be mistaken for mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Infectious Sialadenitis

Mumps

Sarcoidosis

Etiology

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous multisystemic disease of undetermined origin (Box 8-3). Although no specific cause has been identified, it has been suggested that this disease represents an infection or a hypersensitivity response to atypical mycobacteria. As many as 90% of sarcoidosis patients demonstrate significant titers of serum antibodies to these organisms. In some patients with sarcoidosis, a transmissible agent from human sarcoid tissue has been identified. With the use of molecular biological techniques, mycobacterial DNA and RNA have been identified in sarcoid tissues, raising the possibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis or a related mycobacterial organism as a causative agent. Alternate microbial causes include Propionibacteria and Epstein-Barr and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) viruses.

Clinical Features

Oral soft tissue lesions of sarcoidosis are nodular and generally are indistinguishable from those seen in Crohn’s disease. Parotid swelling may occur unilaterally or bilaterally with about equal frequency (Box 8-4). This is often associated with lassitude, fever, gastrointestinal upset, joint pain, and night sweats, which may precede glandular involvement by several days to weeks. Other salivary glands may also be involved in the granulomatous inflammatory process, leading to xerostomia.

Histopathology

Consistent microscopic findings of sarcoidosis are seen as noncaseating granulomas (Figure 8-11). The granulomas may be well demarcated and discrete or confluent. Within the granulomas are epithelioid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells, which may contain stellate inclusions (asteroid bodies) and concentrically laminar calcifications (Schaumann bodies). A diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate may be seen around the periphery of the granulomas. The caseation-type necrosis that is typical of tuberculosis is absent. Microorganisms are also absent.

Sjögren’s Syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome is the expression of an autoimmune process that results principally in dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca) and dry mouth (xerostomia) owing to lymphocyte-mediated destruction of lacrimal and salivary gland parenchyma (Box 8-5). Other autoimmune conditions, particularly rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, and scleroderma, may also be seen as a component of this syndrome. Lacrimal and salivary gland involvement is often one expression of this generalized exocrinopathy that is lymphocyte mediated.

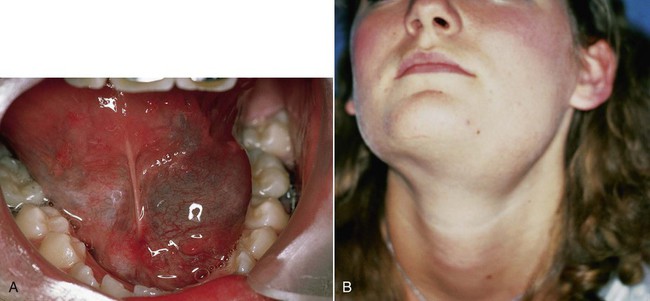

Clinical Features

The chief oral complaint in Sjögren’s syndrome is xerostomia, which may be the source of eating and speaking difficulties. These patients are also at greater risk for dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral candidiasis caused by dry mouth. Parotid gland enlargement, which is often recurrent and symmetric, occurs in approximately 50% of patients (Figure 8-12). A significant percentage of these patients also present with complaints of arthralgia, myalgia, and fatigue.

In the secondary form of Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis is the most common systemic autoimmune disease, although systemic lupus erythematosus is not infrequently encountered (Box 8-6). Less commonly, diseases such as scleroderma, primary biliary cirrhosis, polymyositis, vasculitis, parotitis, and chronic active hepatitis may be associated with secondary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Histopathology

In individuals with Sjögren’s syndrome, a benign lymphocytic infiltrate replaces major salivary gland parenchyma. The initial lesion is focal periductal aggregation of lymphocytes and occasionally plasma cells. As inflammatory foci enlarge, a corresponding level of acinar degeneration is seen (Figures 8-13 and 8-14). With increasing lymphocytic infiltration, confluence of inflammatory foci occurs. Epimyoepithelial islands are present in major glands in approximately 40% of cases and are only rarely seen in minor glands. A positive correlation in the pattern and extent of infiltration between labial salivary glands and submandibular and parotid glands is noted in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses