Rehabilitation of major defects in the craniomaxillofacial region is critical in providing improved quality of life for affected patients. Following oncologic resection, traumatic loss, or congenital anomalies of mid-facial and maxillary anatomy, profound difficulties affecting speech, mastication, bolus transportation, and facial esthetics are common. In addition to functional impairment, these conditions are associated with varying degrees of psychosocial problems and compromised social integration. Correction of defects in this region may be accomplished by microvascular free flap transfer as a surgical alternative in selected patients. However, in many instances, autogenous reconstruction may be precluded because of compromised patient tolerance for complex and protracted surgery, absence of a qualified surgical team, or simply patient preference.

Professor Per-Ingvar Brånemark noted a commonality among three groups of patients: those with an atrophic, fully edentulous maxilla, patients with cleft palate deformities, and those who have undergone maxillectomy. He observed that surgeons were invariably confronted with deficient bone volume for anchorage of implants in the region of the defect or the posterior maxilla. In an effort to reduce surgical morbidity and simplify treatment, Brånemark considered the possibility of using the dense compact bone of the zygoma as an anchorage site for an implant-supported prosthesis. After several iterations and based on anatomic measurements and clinical experience, longer machine-surfaced titanium implants with lengths ranging from 35 to 55 mm were developed for clinical trials. Following the initial pilot studies by Brånemark during the years 1989 to 1994 in which use of the zygoma implant was evaluated, retrospective and prospective clinical trials were conducted in multiple centers.

In a prospective 16-center evaluation with 3-year follow-up, Kahnberg and co-authors reported a 96.3% survival rate. Malevez and associates retrospectively found a 100% survival rate for 103 zygoma implants in 55 patients after 6 to 48 months of loading. Brånemark and colleagues described their results in 28 consecutive patients with severely resorbed edentulous maxillas; 52 zygoma implants were monitored for 5 to 10 years and had a survival rate of 94% and no significant complications.

Although the zygoma implant penetrates the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus, the health of the maxillary sinus does not appear to be adversely compromised by the presence of the implant. Petrusson performed rhinoscopy and sinuscopy in 14 patients 16 to 64 months after placement of zygoma implants and found no signs of sinus inflammation around the implants. Fifty-two immediately loaded zygoma implants in 26 patients were evaluated via paranasal sinus computed tomography (CT) preoperatively and postoperatively by Davó and co-workers. After an average 21.9 months’ follow-up, these authors found that 15% to 20% of patients had asymptomatic mucosal thickening. Two of the maxillary sinuses demonstrated opacity on CT, but following ear, nose, and throat (ENT) evaluation, both merited only follow-up, not surgery. No oral-antral fistulas or other paranasal sinus complications were identified.

The first maxillectomy patient was treated with a zygoma implant by Brånemark and Higuchi in 1999. Since then, multiple centers have effectively used single and multiple zygoma implants in rehabilitating maxillectomy defects.

The Zygoma Implant in Patients with Posterior Maxillary Atrophy

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

The exact cause of maxillary atrophy is unclear, but it is related to the premature loss of teeth. The dental root structure introduces functional stress into the alveolar process that stimulates the density and bulk of the adjacent bone. The maxillary sinus enlarges through childhood as the permanent maxillary dentition descends and erupts. The most inferior point of the floor of the maxillary sinus most closely approaches the alveolar crest at the level of the first molar. This pneumatization process of the maxilla generally ends in eruption of the maxillary second molars, but it can restart following extraction of the first or second molars. Pneumatization of an edentulous posterior alveolus produces loss of much of the alveolar bone, which results in a hollow, shell-like alveolar ridge that initially retains its intraoral contour and allows retention of a conventional denture. Long-term denture wearers experience repetitive superimposition of transmucosally applied masticatory forces on the alveolar ridge that results in vertical or horizontal resorption (or both) and resultant loss of the ridge contour. This can progress to flattening of the alveolus or thinning of the ridge to a knife edge shape. The so-called combination syndrome of natural lower anterior teeth opposing an upper full denture can produce severe atrophy and resorption in the anterior maxilla. Maxillary atrophy can occur anteriorly, posteriorly, or both. Patients with atrophy so advanced that the palate is rendered flat pose the greatest challenge to the prosthetic surgical team ( Fig. 23-1 ).

Pathologic Anatomy

Maxillary Atrophy

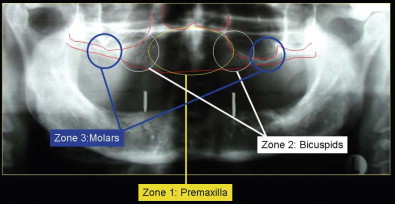

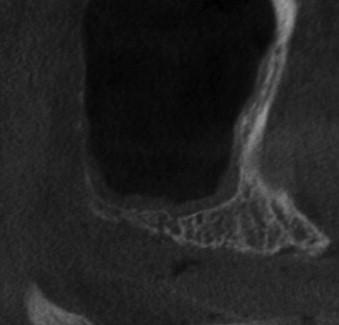

Bedrossian and associates divided the maxilla into three zones of potential atrophy, and their classification aids in understanding the use of zygomatic and other implants in this patient group ( Fig. 23-2 ). Edentulous patients with an eggshell-thin posterior maxillary alveolus (zone 3) who retain 4 mm or less of vertical bone height are not candidates for simultaneous posterior implant placement and sinus lift bone grafting ( Fig. 23-3 ). The 1994 Academy of Osseointegration Sinus Graft Consensus Conference reviewed the results of 2997 implants placed in 1007 grafted sinuses. After a minimum 3-year post-restoration follow-up, a 61% failure rate was found when implants were placed simultaneously with sinus lift bone grafts. A recent review of published papers that compared implant survival in the posterior maxilla between grafted sinus floors versus implants placed into native bone showed greater variability in implant survival for implants placed in grafted sinus floors.

The efficacy of tilted implants has been well documented. Edentulous patients who are fortunate enough to have adequate bone in the incisor-canine region (zone 1), as well as the premolar region (zone 2), may be candidates for the simpler option of tilting the most distal implants to extend the fixture’s location distally to the second premolar–first molar area as described in the “all on 4” technique ( Fig. 23-4 ). Although the “all on 4” technique is generally used with fixed, detachable prostheses, conventional fixed bridgework is also an option with tilted implants combined with mesial conventional implants.

Patients with combined zone 2 and zone 3 atrophy must choose between staged sinus lift bone grafting followed by multiple conventional root-form implants and the graftless, single-stage option of zygoma implants. The zygoma implant may also appeal to patients with zone 2 and 3 atrophy who simply want to expedite their treatment plans. Patients with maxillary atrophy are often elderly and may have medical co-morbid conditions that make them better candidates for a single operation to place all their implants. Such medically fragile patients may be less suitable for a multistep, multiple-surgery treatment plan involving staged sinus lift grafting followed months later by subsequent conventional root-form implant placement.

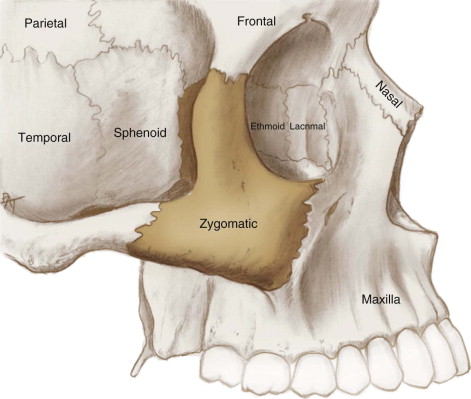

The Zygomas

The paired zygomas occupy the anterolateral corners of the mid-face. They form most of the floor and the anterolateral walls of the orbit, as well as the roof of each maxillary sinus ( Fig. 23-5 ). Their functional significance is to transmit mandibular masticatory forces generated by the pterygoid-masseteric sling and temporalis musculature vertically from the maxillary molar region to the anterior skull base. The body of the zygoma tends not to change its morphology, even in the presence of severe atrophy of the adjacent maxillary alveolus.

Zygoma Implants

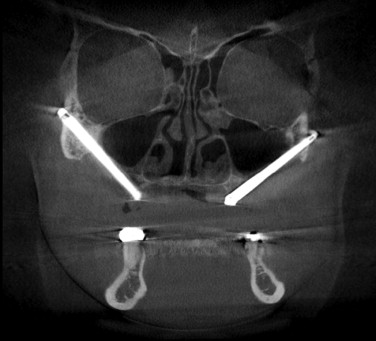

The length of zygoma implants ranges from 30 to 55 mm, and their diameter tapers from 4 mm superiorly to 5 mm at the fixture level ( Fig. 23-6, A ). Implant integration occurs within the thick bone in the body of the zygoma, which produces an integrated length in the range of 15 to 20 mm. Acquisition of an additional zone of integration at the level of the alveolus is welcome, but unnecessary. The path of the zygoma implant lies along the crest of the zygomaticomaxillary buttress (ZMB), and its external hex fixture head emerges in the second premolar–first molar area ( Fig. 23-6, B ). The fixture is angulated at 45 degrees (Nobel Biocare, Yorba Linda, Calif.) or 55 degrees (Southern Implants, Irene, South Africa) to orient it roughly parallel to the occlusal plane ( Fig. 23-6, C ). The long moment arm of the zygoma implant makes it inappropriate to use without cross-arch stabilization to other conventional implants ( Fig. 23-7 ) or to anterior conventional implants plus a zygoma implant on the opposite side ( Fig. 23-8 ).

Conventional, edentulous patients are best served by zygoma implants with a fully textured and threaded surface, which allows the potential for optimal integration anywhere along the buried implant shaft. Conversely, maxillectomy patients require daily cleansing of their maxillectomy defects, which are open to the oral cavity. Hygiene considerations of the exposed implant shaft within the maxillectomy defect may be addressed with either a smoothly machined, threaded, but non-textured implant (Nobel Biocare) or an implant with a smooth, non-threaded shaft extending through the maxillectomy defect with threads only on its apical aspect (Southern Implants).

Diagnostic Studies

History and Physical Examination

The history and physical examination should focus on the condition of the patient’s paranasal sinuses in general and the maxillary sinuses in particular. Acute sinusitis is a contraindication to placement of zygoma implants, but chronic sinusitis is not, provided that the sinusitis is under adequate medical control. Conditions that adversely affect maxillary sinus drainage such as allergic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps, chronic fungal sinusitis, and severe septal deviation may be reasons for preoperative ENT evaluation. A patient with a previous chronic sinus condition will still probably have that condition following the placement of zygoma implants. Preoperative documentation can be helpful to avoid refocusing the patient’s sinus complaints on the zygoma implant.

Physical examination of the oral cavity in contemplation of placement of zygoma implants should include assessment of the patient’s ability to open the mouth widely. The presence of mandibular teeth in the canine-premolar area represents a relative contraindication because of their potential for interference with the long path of instrumentation needed to place zygoma implants. Care in retraction and protection of both hard and soft tissues, as well as creative adjustments in the angulation of the drilling and implant placement apparatus, can circumvent the spatial encumbrance of opposing teeth, but such adjustments are much easier under full general endotracheal anesthesia with pharmacologic neuromuscular blockade ( Box 23-1 ).

Indications

-

Moderate to advanced posterior maxillary alveolar atrophy

-

Atrophic patient who insists on continuous wear of the denture

Relative Indication

-

Maxillofacial defects resulting from tumor or trauma

Contraindications

-

Inability to adequately open the mouth

-

Acute sinusitis

Relative Contraindications

-

Unilateral defects

-

Uncontrolled chronic sinus disease

-

Presence of mandibular dentition (may interfere with surgical access)

Imaging Studies

Some form of CT of the maxillofacial structures and paranasal sinuses is helpful in planning surgery, ruling out significant sinus pathology, and optimizing zygoma implant positioning. The low cost and very low levels of radiation associated with cone beam CT make it preferable to medical paranasal sinus CT, but either will suffice. CT measurement from the zygomatic notch to the crest of the maxillary alveolar ridge will help anticipate the length of the zygoma implant but will provide values that tend to be slightly longer than the actual length of the implant required at surgery. CT evaluation of the atrophic anterior maxilla is also of critical importance to the entire treatment plan. In a patient with diffuse maxillary atrophy (zones 1, 2, and 3), it is often the conventional implants placed in the atrophic anterior maxilla that may be unsuitable for immediate loading. An innovative alternative for such patients can be the use of bilateral, double zygoma implants reported by Schmidt and colleagues for maxillectomy defects and later reported by Maló and co-authors for non-oncologic, diffusely atrophic patients. In patients with non-oncologic, advanced maxillary atrophy, the path of one or both of the double zygoma implants may lie outside the maxillary sinus.

Treatment/Reconstructive Goals

The goal of the zygoma implant is to provide a posterior implant fixture in a patient who is unsuitable for straightforward placement of a conventional root-form implant in this location.

Although the path of a zygoma implant lies partially or totally within the maxillary sinus, its position at the ZMB is remote from the sinus drainage ostium ( Fig. 23-9 ). Treatment with zygoma implants should not predispose to sinus pathology. Endoscopic evaluation of the maxillary sinus after placement of zygoma implants has shown no evidence of infection or inflammation.

Advantages of the zygoma implant in a patient with standard maxillary atrophy include the ability to place the implant along with anterior maxillary implants in one surgical stage, thereby avoiding sinus grafting. Postoperatively, the patient is able to wear a conventional denture over the healing implant if immediate loading is not done. Disadvantages include the more extensive dissection required for placement and the need for the surgeon to be familiar with antral, zygomatic, and orbital anatomy. The need for at least deep intravenous sedation, if not general endotracheal anesthesia, could be viewed as a potential disadvantage.

Specific Treatment and Techniques

Surgical Techniques

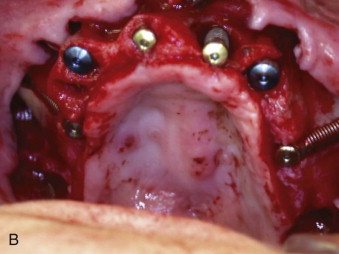

Brånemark Standard Technique

Zygoma implants are optimally placed in a surgical center or hospital operating room under general nasoendotracheal anesthesia, although the procedure can be done under deep intravenous sedation. Complete mid-facial local anesthesia is especially important if sedation is used. A full crestal incision is made along with anterior midline and bilateral posterolateral relaxing incisions. This allows wide access to the zygomatic body, ZMB, and the anterior maxilla. If condemned maxillary teeth are present, they are removed, followed by appropriate alveolectomy. In a full-arch implant procedure, the anterior implants are placed first. Most such patients will require four conventional anterior implants, although three will suffice. Two are absolutely necessary. Conventional anterior implants should be placed on the palatal aspect of the alveolar ridge, in combination with appropriate alveolectomy and peri-implant grafting as needed.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses