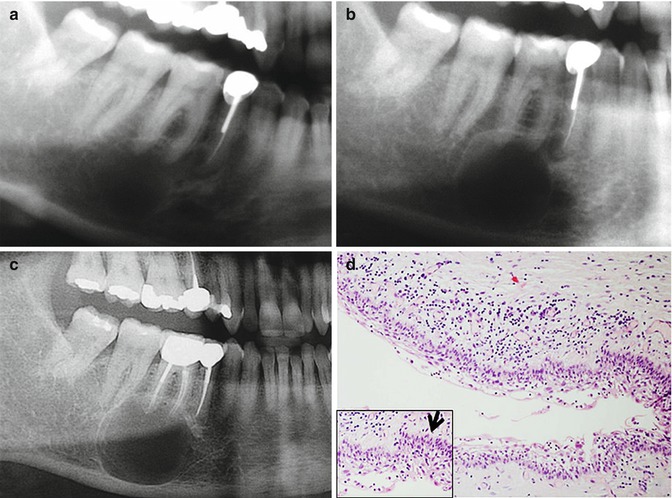

Fig. 2.1

Endodontic surgery on misdiagnosed vertical root fracture on maxillary premolar. (a) Presurgical; (b) immediately post surgery; (c) follow-up (gutta-percha tracing of buccal and palatinal sinus tracts); (d) following extraction – a vertical root fracture was diagnosed

When VRF diagnosis is made, a quick decision to extract the tooth or root is necessary, since that the inflammation in the supporting tissues would otherwise lead to periodontal breakdown followed by the development of a deep osseous defect [7] and resorption of the bone facing the root fracture. Thus, failure to diagnose VRF during the endodontic surgery might lead to treatment failure associated with excessive bone loss that will jeopardize future restoration of the area of the extraction [8].

Non-endodontic Lesions Mimicking Inflammatory Periradicular Lesions in Endodontically Treated Teeth

Pulp sensitivity testing has been frequently suggested for differential diagnosis between apical lesions of endodontic and non-endodontic origin [36]. However, most teeth scheduled for endodontic surgery were previously endodontically treated. Thus, the diagnosis cannot be based on pulp sensitivity testing.

In general, tissue removed from a periradicular area of teeth with apical periodontitis, when submitted to histopathological examination, demonstrates a granuloma or a radicular cyst. However, on rare occasions, histopathological examination of tissues removed from this area will reveal lesions of other entities, which radiologically mimic periradicular inflammatory pathoses. Although radicular cysts and granulomas are very common, we should be aware of the possibility that other noninflammatory lesions may be located in a periradicular location. This is important since these other missed or disregarded diagnoses might result in inappropriate treatment.

Periapical granulomas (PAGs) are formed at the apices of non-vital teeth, most of them being asymptomatic. In general, PAGs represent ~75 % of apical inflammatory lesions and ~50 % of periapical lesions related to lack of response to endodontic treatment [37]. Radiographically, PAGs are radiolucent lesions ranging from small, nearly indistinguishable to lesions of 2 cm in diameter and larger. The involved tooth shows loss of lamina dura (LD) at the apical region. PAGs may be circumscribed or ill defined, with or without a radiopaque rim. Root resorption is quite common. PAGs are biologically dynamic lesions and can transform into periapical cysts (PACs) or periapical abscesses, without necessarily alternating the radiographic features. Although PACs are believed to achieve a larger size than PAGs, distinguishing between these two entities based on the radiographic findings is almost impossible [37].

A cyst associated with a non-vital tooth may develop at the lateral aspect of the root due to spread of the pulpal necrotic material through a lateral root canal and foramen and is termed lateral radicular cyst (LRC). In principle, the radiographic features of LRC are identical to those of PACs/PAGs including the radiolucent nature of the lesion and loss of the LD in the region of the foramen of the root canal [37].

Lesions located at the apices of non-vital teeth that radiographically look like PAGs/PACs, but histologically reveal to be lesions of a large range of entities, have been described in the English language literature, in either single-case reports or limited case series. It is assumed that between 0.65 % and ~6 % of apparently periapical lesions are not of inflammatory origin [38–41]; therefore, comprehensive diagnostic evaluation is needed in order to avoid pitfalls of unnecessary endodontic treatment. The lesions mimicking PAGs/PACs can be classified as follows: anatomical structures and variations, cysts, tumors and diseases, and miscellaneous lesions.

Anatomical Structures and Variations

The incisive canal is located between and apical to the roots of the maxillary central incisors. It is generally accepted that a diameter of 6 mm is the upper limit of the normal size for the incisive canal, so that a radiolucency of 6 mm or smaller in this area is usually considered a normal foramen unless there are clinical signs or symptoms (e.g., swelling, pain, drainage) present [37]. Lesions larger than 6 mm are usually considered as an incisive canal cyst. The incisive canal or the incisive canal cyst usually appears as a symmetrical, well-defined radiolucent lesion between the roots of the upper central incisors, showing a “heart”-like-shaped outline due to its superimposition on the anterior nasal spine. However, occasionally, the canal or its cystic variant is asymmetrical, lying only on one side of the midline, overlapping the apex of the adjacent central incisor, thus mimicking a periapical pathosis. In this case, in particular when the lesion is larger than 6 mm, an occlusal radiograph will aid in determining the spatial relation between the seemingly unilateral “periapical” pathosis and the status of the LD and width of the periodontal ligament of the adjacent tooth [37].

The mental foramen may also have a radiographic appearance of a periapical pathosis in the area of the lower second premolars. If doubts are raised in regard to the true nature of the lesion, then additional periapical x-rays should be taken from different angles in order to analyze changes in the position of the “periapical” finding [37].

The anatomical depression at the angle of the mandible below the inferior alveolar nerve canal, in which part of the submandibular salivary gland or muscle tissue or fibro-fatty tissue resides and has a radiographic appearance of a cyst-like lesion, is known as the mandibular lingual salivary gland depression/Stafne defect/static bone cyst [37]. In a minority of cases, this anatomical mandibular defect has been found more anteriorly, namely, starting from the symphysis area to the premolars. This anterior variation of “Stafne bone defect” is filled by sublingual salivary gland tissue and has the appearance of a periapical pathosis [42].

Anecdotal cases of atypical anatomy of the maxillary sinus with an extension seen on conventional panoramic x-rays as a unilocular, well-defined corticated radiolucency in the second premolar-first molar location were reported [43]. With the aid of adequate CT imaging, when indicated, it could provide valuable information for an exact diagnosis.

Another rare anatomical variation is the canalis sinuosus that carries the anterior superior dental nerve and associated blood vessels [44]. It can rarely take an aberrant route between the medial aspect of the alveolar bone of the maxillary canine and the nasal cavity and as such be interpreted as a periapical pathosis of the canine tooth. Close examination of periapical x-rays will reveal the intact periodontal ligament space of the canine upon which the radiolucency of the canalis sinuosus is superimposed.

Odontogenic Cysts

A true cyst is defined as a pathologic cavity lined by epithelium and filled with fluid or semisolid material [37]. Cysts rarely develop within bones for the simple reason that it is unusual to find epithelium in these locations. The jawbones, however, are a marked exception to this rule, and cysts occur in this region more frequently than in any other bone in the body. The source of epithelium in the jawbones is both odontogenic and non-odontogenic. Corresponding to this epithelium, two major types of bone cysts, odontogenic and non-odontogenic, arise within the jaws. The odontogenic cysts can be further classified as developmental (part originates from the rests of dental lamina and part from reduced enamel epithelium) and as inflammatory (originates from the rests of Malassez) [37]. Cysts of jawbone are well-defined, totally or predominantly radiolucent, sometimes expansile lesions.

The lateral periodontal cyst (LPC) is a rare developmental odontogenic cyst that typically occurs on the lateral surface of a canine or a premolar tooth, predominantly in the lower jaw [37]. Adjacent teeth are vital and as such the LD and periodontal ligament space are expected to be intact. Radiographically, LPC is a well-defined radiolucency on the lateral aspects of the tooth roots with a diameter of ~1 cm. These clinical and radiographic parameters should be enough to distinguish a LPC from a LRC. However, LPC type of lesions can be present in association with a non-vital tooth or with what seems to be lack of healing of an endodontically treated tooth [37]. Upon submitting the lesion to microscopic examination the diagnosis of LPC has to be supported by the typical features of the lining epithelium (that are expected to be preserved, at least in part, even if the cyst is inflamed).

Another rare odontogenic developmental cyst reported at the apex of a non-vital tooth is the orthokeratinized odontogenic cyst [45] that usually has no characteristic clinical or radiographic features to distinguish it from other inflammatory cysts.

Odontogenic Tumors

Odontogenic tumors arise from epithelial and/or mesenchymal components of the developing odontogenic apparatus and are almost always confined to the jaws. These tumors are usually benign but vary widely in their behavior.

Radiographically, they may manifest as totally radiolucent or radiopaque lesions or as mixed radiolucent-radiopaque lesions. The lesions are diagnosed and classified on the basis of their histologic features, usually correlating the clinical and radiographic features.

The keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KCOT), formerly known as odontogenic keratocyst, is a developmental odontogenic lesion, now believed to represent a cystic tumor [37]. KCOT may demonstrate a radiographic picture that, among other possibilities, can mimic that of a PAG/PAC [37]. In fact, when large series of periapical biopsies taken from teeth with clinically necrotic pulps were analyzed, KCOTs were found in a frequency ranging from 0 % [38, 46, 47] to 0.27 % [40], 0.3 % [48], 0.53 % [49], and up to 0.7 % [50]. Comparing KCOT to other periapical noninflammatory types of lesions, it seems that KCOT is the most frequently encountered. In a study of 239 KCOTs, 21 (9 %) were located periradicularly and 12 (57 %) were associated with non-vital teeth or endodontically treated teeth and therefore were considered to be of endodontic origin [51]. Interestingly, in the latter lesions, two-thirds were symptomatic, the mandible-to-maxilla ratio was almost 1:1, 90 % were associated with teeth anterior to the molars, mainly anterior teeth, and the mean age of the patients was 56 years. These features are different than those that characterize the classical non-periapical, non-vital tooth-related KCOT, in terms of location and age of patients [37]. Periapical lesions that fail to heal after good-quality endodontic treatment require further investigation, in particular if lesions continue to enlarge and/or present aggravating symptomatology during follow-up. A 4-year follow-up period has been suggested in order to assess success or failure [52]. Assuming that the nonhealing periapical lesion could be a KCOT, it is likely that during this follow-up period it would continue to advance and change the radiographic picture, thus demanding a biopsy procedure and a definite microscopic diagnosis. A case of KCOT mimicking a periapical lesion is seen in Fig. 2.2. The treatment of KCOT must take into consideration the tendency for recurrence, and therefore the surgical approach is usually more aggressive than for other developmental cystic lesions nonetheless periapical inflammatory pathoses and usually comprises of removal of the lesion followed by peripheral ostectomy of the bony cavity and/or chemical cauterization. Exceptionally, locally aggressive KCOTs demand local resection and bone grafting [37].

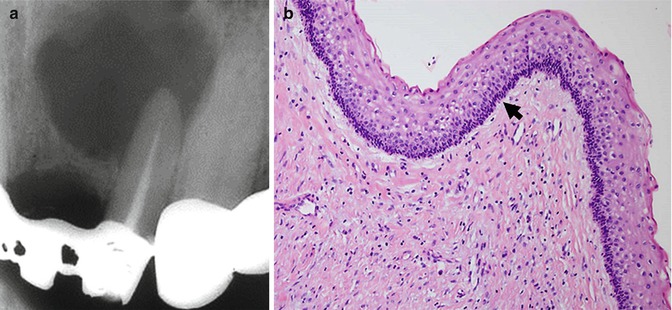

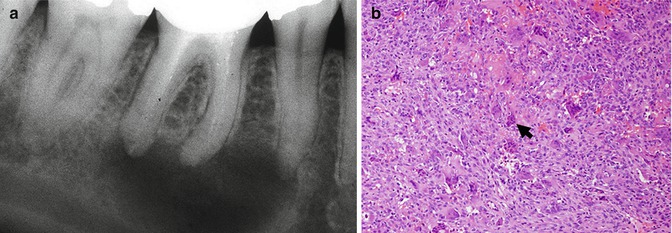

Fig. 2.2

A case of KCOT mimicking a periapical lesion. (a) The radiograph shows a radiolucent lesion in the periapical region of the left upper lateral incisor that is non-corticated and defined in the lower portion; however, in the upper portion there is a notion of blurred margins. (b) The hematoxylin- and eosin-stained slides showed a cystic lesion lined by stratified squamous epithelium with parakeratin showing a slightly corrugated surface. The epithelium is of regular width and shows a palisading arrangement of the basal nuclei (arrow). These histopathological features are consistent with keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KCOT). Original magnification ×200

Anecdotal cases of solid ameloblastoma appearing as a periapical, cyst-like radiolucency associated with non-vital teeth have been reported [53, 54]. Similarly, unicystic ameloblastoma adjacent to vital and non-vital teeth was reported [36, 55]. A case of a “periapical” unicystic ameloblastoma considered to be an inflammatory periapical lesion that remained untreated for about 10 years is illustrated in Fig. 2.3. The treatment approach for solid, multicystic ameloblastoma and for unicystic ameloblastoma with mural proliferation is quite aggressive because the tumor infiltrates into the adjacent cancellous bone, beyond the apparent radiographic margins [37]. The most conservative treatment is removal of the tumor after careful study of the CT scans followed by peripheral ostectomy. Escalation of the surgical procedure to marginal resection followed by reconstructive surgery might be mandatory depending on tumor size and pattern of expansion, yet a 15 % recurrence rate still occurs. The other types of unicystic ameloblastoma (i.e., the luminal and intraluminal) are treated as “conventional” cysts by enucleation and close follow-up as recurrence rates of 10–20 % were reported [37]. Additional types of rare odontogenic tumors in a periapical location were published, either as single-case reports or as part of case series on periapical inflammatory lesions, and these include adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor, ameloblastic fibroma, squamous odontogenic tumor, calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor, and odontogenic myxoma [38, 40, 56, 57]. Part of these reported lesions were not accompanied with photomicrographs of the histopathological findings, so that the accuracy of the diagnoses cannot be always confirmed.

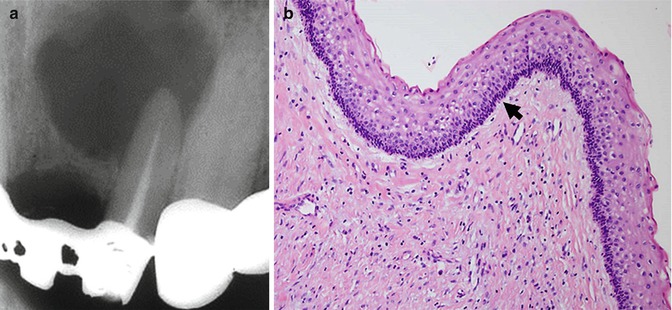

Fig. 2.3

A case of a “periapical” unicystic ameloblastoma (a) In 2002, an asymptomatic periapical lesion showing a corticated, round-shaped radiolucency at the apical area of the first right molar. (b) In 2005, the lesion continued to grow. (c) 2013 – a root canal treatment was performed; however, the lesion continued to grow. (d) Histopathologically, a cystic lesion is seen. The lining epithelium shows a basal layer of columnar cells with hyperchromatic nuclei with reverse polarity arranged in a palisading pattern highlighted in the inset with an arrow. The rest of the epithelial cell layers have an appearance reminiscent of stellate reticulum. There is a mild chronic inflammatory infiltrate. The histopathological features are consistent with a unicystic ameloblastoma, luminal type. Original magnification ×200

In conclusion, the key to an accurate diagnosis in case of a periapical lesion, even if it looks to be of inflammatory nature, is the collection of all available clinical data and radiographic findings and sufficient follow-up period in those doubtful cases.

Bone Tumors and Diseases

This is a diverse group of lesions of varied etiologies; we will presently focus on two entities that radiologically have features of a radicular cystic lesion, namely, central giant cell granuloma (CGCG) and fibro-osseous lesions.

CGCGs appearing as small periapical lesions constituted 9 % of all examined CGCG cases (N = 75) in one study [58]. Furthermore, the largest retrospective study on CGCG (N = 79) found in a periapical location (PA-CGCG) revealed that 20 % of the lesions were associated with teeth with necrotic pulps and that the majority of these necrotic teeth had been endodontically treated [59]. In addition, PA-CGCG was encountered in patients older than 30 years of age, while the non-PA-CGCG is usually diagnosed in younger patients; ~50 % of the PA-CGCGs were in the posterior area of the mandible; in regard to the PA-CGCG found in the maxilla, there was a similar distribution between the anterior and posterior areas. Single cases of PA-CGCG or small case series were also reported [38, 40, 60–62]. All these studies emphasized the need for careful analysis of the radiographic findings in order to decide the lesion-tooth supporting structures relations, both at the initial presentation and during the follow-up period, if teeth were endodontically treated in equivocal cases. Whenever surgical specimens are taken, submission to microscopic evaluation is mandatory. A case of CGCG mimicking a periapical lesion is seen in Fig. 2.4. CGCGs are usually treated by thorough curettage although recurrence rates of 11 % and up to 50 % were reported, with the higher values being attributed to those lesions that are defined as biologically aggressive and which are characterized by a tendency to recur, especially in young patients [37]. Recurrent CGCGs may be treated by curettage or by a more radical surgical approach, depending on the clinical findings, with optional addition of different pharmacological agents.

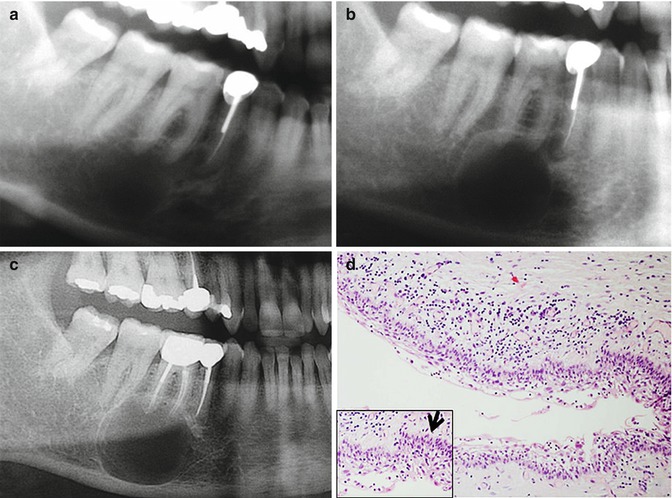

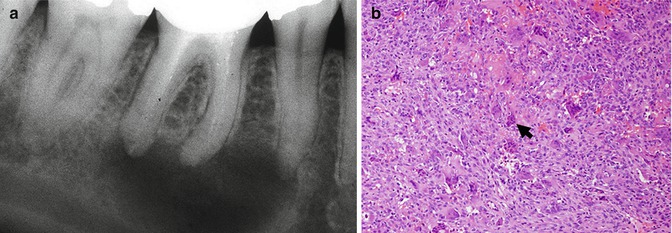

Fig. 2.4

Central giant cell granuloma mimicking a periapical lesion. (a) A radiolucent, non-corticated, usually defined lesion is seen at the apical area of the right first mandibular molar. (b) Histopathologically, there is a hypercellular mass consisting of multinucleated giant cells (arrow) admixed with mononuclear spindle cells in a stroma showing extravasation of red blood cells. Original magnification ×200

Fibro-osseous lesions of the focal or periapical type [focal cemento-osseous dysplasia (FCOD) and periapical cemental dysplasia (PCD)] can be confused with PAGs/PACs in their early, radiolucent stage [63, 64], although, at least PCD, rarely affect only one tooth. Whenever diagnosis based on clinical and radiographic information is doubtful, biopsy of the periapical lesion should be considered before starting a redundant endodontic treatment.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses