The executive and legislative branches of state government have broad authority that provides the underpinning for the dental health care system. This article describes four principal areas in which policy makers’ decisions can improve children’s access to dental care: (1) providing and financing health care (ie, providing opportunities for shaping public insurance programs like Medicaid and SCHIP); (2) regulating health providers and facilities (ie, providing levers for policy change in dental practice acts); (3) ensuring the health of the public (ie, states’ choices on population-based approaches and providing leadership in oral health); and (4) education and training of the health workforce (ie, state support of dental education that can ensure a dental workforce that meets the needs of the population).

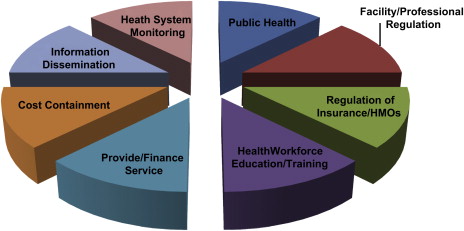

Given the large degree of control that the profession of dentistry has over its education, licensure, and practice, it is easy to overlook the fact that state policymakers have the primary authority and responsibility for regulating the health professions. That authority is rooted in the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which reserves for the states, or the people, any power not given by the framers to the federal government. State control over health providers is not limited to police power over activities that threaten public health and safety. In fact, states have broad authority that provides the underpinning for the health care system, performing a number of critical functions, some of which they share with federal or local governments: (1) providing and financing health care; (2) regulation of health practitioners and facilities; (3) ensuring the health of the public; (4) health workforce education and training; (5) regulation of insurance; (6) cost containment; (7) informing the public about the functioning of the health system; and (8) monitoring the system. Each of these functions has been employed creatively to expand access to care for underserved populations. This article describes the authority that states have in the first four areas, where state policymaking is most visible and powerful, and how it can be used to expand access to care for low-income children Fig. 1 .

Provide and finance care

The first critical function of states is to provide dental health care to a large portion of Americans. State or county-employed dentists care for people who are in state custody, such as residents of state-run institutions for people who have developmental disabilities and prisoners, as well as for patients of government-operated clinics or local health departments. The state is also a purchaser or funder of health services for children and adults enrolled in public insurance programs. In this role, the state has great power to shape incentives and disincentives for these people to obtain dental health care and for dental and medical practitioners to provide it.

Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program

Medicaid is one of the cornerstones of the American health care system. Although it covers only certain categories of low-income people, not all of them, it nevertheless is the foundation for the health care safety net. As of June 2006, Medicaid, together with the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), covered 25.7 million children. These programs are funded jointly by state and federal governments. The federal government sets broad guidelines for the program, but states have a considerable degree of flexibility in setting policy in three areas: who is eligible for the program, what benefits they receive, and how those benefits are delivered.

Medicaid generally covers four categories of low-income people: children, their parents, pregnant women, and the “aged, blind, and disabled,” which includes low-income Medicare recipients and people eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). States also can cover other groups of enrollees, such as young adults exiting foster care. SCHIP builds on Medicaid by providing states with enhanced funding to enroll children in “working poor” families (typically, those who have an income less than twice the federal poverty level) with benefits similar to those of Medicaid or private large-group insurance.

Medicaid-enrolled children are entitled to coverage of all medically necessary dental services through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit. Although the provision of dental services is not required under SCHIP, all states except one currently provide them, and the proposed 2007 federal legislation to reauthorize SCHIP would have made dental coverage a requirement. When states have fallen short in their obligation to provide children’s dental services, advocates frequently have filed suit against them for failure to meet the federal standard that Medicaid enrollees have access to health care professionals comparable to that of other people in their community. Of 27 dental-access suits filed in 21 states, states have lost or settled all but 4.

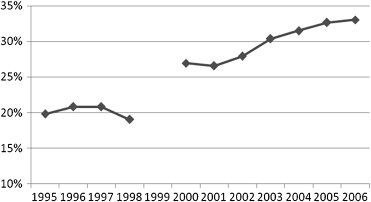

Despite the EPSDT requirement to provide dental services, states persistently have had trouble delivering these services and could do more to improve access. Data reported to the federal government show that in 2006 only one third of all children enrolled in Medicaid received any dental service. Although this percentage is an improvement from previous years ( Fig. 2 ), it still falls far below the 57% use rate among privately insured children in 2004.

One of the crucial levers policymakers have for improving children’s dental health is the ability to provide a meaningful Medicaid dental benefit to adults. Research has shown that coverage of a health care service for parents influences whether those parents seek that care for their children. Addressing the oral health needs of new mothers, as well as providing education and anticipatory guidance, can have positive oral health benefits for entire families. A pilot program in Klamath County, Oregon, is seeking to test this hypothesis by providing home visits and intensive oral health services for pregnant women and new mothers. Also, Medicaid benefits for adults change the equation for providers. It is easier for community health centers and clinics to sustain a healthy business model and to treat all comers if reimbursement is available for adults. Medicaid reimbursements to private dental providers also are very helpful in rural and underserved areas, where the population is poorer and less likely to have private dental coverage. Adult dental services are “optional” in Medicaid, however, and many states choose to limit coverage to emergency services or to provide no coverage at all. This situation is in stark contrast to private dental coverage, which rarely covers children without also covering policy holders and their spouses.

Policymakers in states considering comprehensive health care reform have a variety of choices in crafting a dental benefit in their programs. To date, state health care reform efforts have not included dental benefits in any systematic way, although there have been some positive steps. For example, during comprehensive reform in Massachusetts in 2006, dental benefits were extended to children enrolled in Medicaid-style benefits through Commonwealth Care and were restored to low-income adults. The state also arranged for supplemental payments to Federally Qualified Health Centers and to some public hospitals that provided dental care to people who did not have dental benefits. An option for policymakers to consider is the design of a buy-in benefit that looks more like Medicaid, with lower cost-sharing by enrollees and more protections for new enrollees at lower incomes, and more like state or federal employee health plans for higher-income uninsured persons.

Once policymakers have determined which enrollees will have dental benefits, the state must decide how those benefits will be delivered and what resources will be allocated to deliver them.

Reimbursement Rates

The size and structure of payment is a critical policy lever. Inadequate payment is the central reason dentists cite for not enrolling as providers in state Medicaid programs. Federal Medicaid law requires states to “assure that payments are … sufficient to enlist enough providers so that care and services are available under the [Medicaid] plan at least to the extent that such care and services are available to the general population in the geographic area.” This federal standard has not been effectively or widely enforced, however, because, among other reasons, there is contention about what consititutes “sufficient” reimbursement. The American Dental Association’s (ADA’s) position is that rates set at the 75th percentile of regional fees (that is, payment rates that are as high as or higher than the retail charges of three fourths of dentists in a geographic area) is a sufficient level to attract provider participation. State experience, however, shows that more modest rate increases still can generate adequate provider participation if reimbursement at least covers dentists’ costs of providing the care. States understand that rate increases, coupled with use increases, can cause large spending hikes; Alabama tripled its total Medicaid dental expenditures as a consequence. Still, because dental spending is less than 5% of Medicaid expenditures, and costs are shared between the state and federal government, the fiscal impact of reimbursement rate increases on state budgets is modest. For example, the increased dental expenditures in Alabama amounted to only 1.15% of total Medicaid expenditures of $3.86 billion in 2004. As Table 1 shows, increases of the reimbursement rate in three states helped them meet their goals of improving the use of services among Medicaid enrollees. Advocates in states such as Wisconsin have proposed a small surcharge on sugary drinks to fund reimbursement rates that keep pace with inflationary increases.

| Comparator | Alabama | South Carolina | Tennessee | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2004 | Percent Change | 2000 | 2004 | Percent Change | 2002 | 2004 | Percent Change | |

| Number of enrollees using services | 72,287 | 155,541 | 115 | 162,567 | 256,782 | 58 | 131,899 | 286,314 | 117 |

| Total dental payments ($ million) | 11.5 | 44.4 | 288 | 48.2 | 89.3 | 85 | 28.7 | 130.3 | 355 |

| Payment per user ($) | 159 | 286 | 80 | 296 | 348 | 18 | 217 | 455 | 110 |

If across-the-board hikes in the reimbursement rate are not possible, strategies targeted at populations of particular interest show promise. New Mexico, for example, has used incentive payments to develop a small cadre of dentists to provide care to people who have developmental disabilities. Pennsylvania is experimenting with pay-for-performance strategies to give dentists incentives to provide a continuing “dental home” for young children, pregnant women, and people who have chronic conditions such as heart disease and diabetes.

Administration

Although reimbursement rates that at least cover dentists’ costs of providing care are necessary, they alone are not sufficient to increase provider participation and enrollee access to care. States need to address the “hassle factor,” too. Most dental offices are small and have limited administrative capacity, and even less inclination, to navigate complex Medicaid program rules. Many dentists’ offices expect full payment at the time of service and expect patients to file claims for their own insurance. Therefore, states can enhance dentists’ participation if they make it easy for offices to participate in the program, to see patients in need, and to receive reimbursements in a timely fashion. Several states—Tennessee, Virginia, and Massachusetts, among others—have addressed these concerns by “carving out” dental administration and contracting with a specialized vendor for “administrative services only (ASO),” to process claims, make determinations on coverage for services, and maintain provider and enrollee hotlines. Other states, such as Alabama, have addressed many of the same concerns through administrative improvements by the Medicaid agency. Any administrative arrangement—by managed care companies, ASOs, or directly by states—can succeed only if it has sufficient resources, dedicated staff, and leaders who are focused on dental services as a priority.

Availability of Medicaid Reimbursements

In their role as purchasers of care, states can decide whether to support models of care delivery that go beyond the traditional private dental office. Because of government’s purchasing power, these decisions can determine whether a new model of care is sustainable and cost effective. For example, Medicaid reimbursement was key to sustaining the fledgling “Into the Mouths of Babes” program in North Carolina, which trained—and paid—pediatricians and family practice physicians to provide children from birth to 3 years with preventive dental care services: basic oral health assessment, oral health education, and fluoride varnish. Physicians were targeted because young children visit physicians earlier and more often than dentists. Because of the lessons learned from North Carolina, 26 states now use Medicaid reimbursement as a way to encourage physicians to begin attending to children’s oral health as early as possible.

Likewise, 14 states have decided to make Medicaid reimbursements available directly to dental hygienists, rather than having payments go first to a dentist or local health department, who then pays the hygienist. This direct payment enhances the ability of hygienists working in public health settings to reach underserved children. Although hygienists’ costs in providing services are lower than dentists’ costs, reimbursement rates that cover overhead costs are equally important for them. A recent study examining a model for school-based hygiene services found that reimbursement rates had to be at least 60.5% of mean national fees for the model to be sustainable and that only 5 of 13 states examined had fees that met that threshold.

Finally, states can use general fund dollars to leverage the purchasing power of Medicaid (which itself leverages a federal match by state dollars). Wisconsin appropriates $632,000 annually to support a Federally Qualified Health Center with multiple clinics in rural northern areas of the state. The enhanced Medicaid reimbursements to which these clinics have access—which make up the difference between regular Medicaid payment rates and the clinics’ cost of providing care—help sustain large-group dental practices that provide employment for community members and increase Medicaid enrollees’ use of care by allowing them to access that care closer to home.

Regulation of health facilities and professionals

The second critical function that has a significant impact on access to care for children is the regulation of facilities and health professionals. The primary vehicle for this regulation is the state dental practice act, which establishes the legal framework for the practice of dentistry. Dental practice acts define in very broad terms what constitutes the practice of dentistry and who is qualified to obtain a license to practice. This broad authority gives dentists and physicians—and no others—the right to perform any of those functions legally. Licensure for dentists began as an offshoot of medical licensure; the Alabama medical board issued the first dental license in 1841. As the science advanced and techniques and education became more standardized, practitioners sought both recognition of their profession and limits on who could practice legally. In the 1870s, local and state dental societies pressed for and won state licensure and “the elimination of charlatans” from the field. As new types of providers, such as nurses, assistants, and hygienists, were developed, licensure laws were amended to recognize them, to define what services they could perform, and to give physicians and dentists the authority to supervise and delegate authority to them. Legal authority for new providers essentially was carved out of the services physicians and dentists could perform, so that only the whole package of services in the law was defined as “practicing medicine” or “practicing dentistry.”

The fact that this broad authority is set in law places physicians and dentists at the top of the profession, defending its prerogatives against all comers. The difficulty with this situation is that all professions evolve over time, strengthening and expanding their competency, but the law stays the same. Physicians and dentists, once licensed, need not prove their competency to perform any specific function, even though they are not all trained to perform, or are experienced or comfortable in performing, all the functions known to medicine and dentistry. Not everyone who is a dentist can perform complex oral surgery, or do orthodontics, or care for a very young child or a patient who has special needs. Yet, dental hygienists or assistants, or new providers, who seek legal authority to perform specific procedures they have been trained to do—and may be allowed to do in a different state—must prove competency. Legal authority is required before a provider can undertake an expanded scope of practice, but it is difficult to demonstrate that competency when the performance is prohibited. Legislators, most of whom are not clinicians, have great difficulty weighing the conflicting arguments about the safety or risks related to changes in scope of practice for providers. Therefore, dental and medical practice acts are very difficult to amend even though they should be updated regularly to ensure that the public benefits from advances in science, education, and the health care system.

Physicians and dentists see medical and dental practice acts as crucial to their control over their profession. They fight any “encroachments” by other providers seeking amendments to recognize their training or ability to perform new functions. Their objections to changes in the law may not consider objectively the clinical competency of other providers or the quality of care they could provide but rather seem to derive from an interest in retaining hegemony over the profession and an understandable desire to control their ability to operate profitable businesses in the face of uncertain economies and reimbursements. The viability of health care providers’ businesses is and should remain a concern for policymakers; but it should be balanced against the state’s responsibility to ensure access to care for citizens and to promote competition and consumer choice. These considerations are major factors in the regulation of almost all other services and sectors of the economy (eg, transportation, utilities, and telecommunications) and should be no different for medicine and dentistry.

Given the challenges in regulating health providers, change can be slow. Although the integration of dental hygienists into dental practice is a given today, it was not always so. The first state to recognize hygienists was Connecticut in 1907, followed by Massachusetts and New York in 1915 and 1916, respectively. By 1948, only two thirds of the states licensed hygienists, and some limited their practice to schools and clinics because of opposition from organized dentistry. Many dentists in private practice who performed dental cleanings themselves “looked upon this new intruder as a competitor.” Now, most dentists employ dental hygienists. A sizable portion of visits to the dentists, and of private practice income, stems from services hygienists provide.

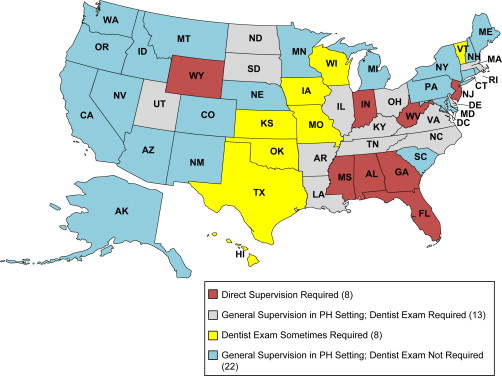

In practical terms, legislatures enact dental practice acts, and state boards of dentistry or dental examiners implement them by writing and enforcing rules and regulations. The fact that this process occurs in each state, rather than at the federal level, leads to a confusing patchwork of laws governing the profession. These laws bear little relationship to the actual clinical competency of the providers they govern or the needs of patients, neither of which vary by jurisdiction, or to the most efficient use of health care resources. Instead, the great differences between what a specific type of provider can do in each state reflects the relative political and financial power of different provider groups, not their education, training, or competency. For example, in Washington State, dental assistants who meet certain requirements in experience and training can apply sealants and fluorides under general supervision in school-based programs, but in eight states registered dental hygienists (who typically have more training than dental assistants) cannot apply sealants without a dentist present. Variation across states in teeth, or patients, or even provider education, does not account for those differences. According to workforce experts at the University of California, “Because legal scopes of practice can facilitate or hinder patients from seeing a particular type of health provider, the regulations have direct impacts on access to and cost of care. Quality of care may also be affected Fig. 3 .”

An example that highlights an opportunity for state policymakers to improve access is the requirement in some states for supervision of hygienists when applying sealants. Sealants are clear plastic coatings applied to the chewing surfaces of molars that keep cavity-causing bacteria from invading. Ninety percent of cavities occur in molars, so a population-based strategy of applying sealants in second and third grade (when a child’s first permanent molars come in) can deliver significant preventive benefits for many years afterward. Most sealant programs target children in at-risk schools and communities, particularly children receiving free or reduced-cost lunch programs, those on Medicaid, and racial and ethnic minorities, who are less likely to have regular access to oral health care. Children in racial and ethnic minorities are three times more likely to have untreated decay and are only one third as likely to receive sealants.

Dental hygienists are widely recognized as the appropriate providers to apply sealants to children’s teeth. In many states, however, organized dentistry has insisted that children be seen by a dentist before a hygienist applies sealants. The requirement that dentists screen a child first and be present while the sealants are applied is scientifically unnecessary and economically impractical. A committee of the ADA issued new guidelines in March, 2008 indicating that sealants are protective against the progression of decay, even if a molar has “incipient decay.” (Detection of “incipient decay” had been the most frequently cited reason for requiring a dentists’ diagnosis before sealant placement. ) Requiring dentists to examine a child raises the cost of sealant programs, makes the programs more difficult to administer (because dentists willing to participate are in short supply), and limits the number of children that can be protected from future decay.

Policymakers have a number of levers at their disposal to affect the regulation of the profession and improve access. Governors appoint members to the state board of dentistry and thus can influence decisions by varying the background and experience of appointees. State legislatures can influence a state board by changing the number and types of members the board should include, such as such as hygienists, public health dentists, and members of the public. Both appointments and membership structure can affect board decisions. In addition, workforce experts cite an “inherent conflict of allowing one professional board to govern members of a different profession” as a reason for establishing a different regulatory structure for each profession. (Thus nurses are self-regulated rather than governed by state boards of medicine.) State policymakers can establish separate committees of a state board to provide advice or to oversee the practice of dental hygiene, can spell out what power those committees have, and can assure the committees’ recommendations to the full board are considered seriously. At least three states have established a separate regulatory structure for hygienists. Since the 1980s, the State of Washington has had a dental hygiene advisory committee that functions independently of the dental commission. New Mexico has had a dental hygienists’ committee since 1994, and Iowa has had one since 1999. These committees make recommendations to the Board of Dental Examiners that must be followed unless some reasonable objection is made.

States also set requirements for licensure and certification that govern the movement of providers between states and countries. State dental practice acts set the requirements for licensure of providers in a state, but state boards have latitude in interpreting the law. Because there is a great uniformity in dental education in the United States, 46 states allow licensure by credential or reciprocity, so that a dentist with a valid license who has been in practice for a set period (usually 5 years) in another state can get a license without sitting for the state examination (only four states do not: Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, and Nevada). The movement of dentists between countries, however, is made difficult or impossible by licensing laws in most states that require all dentists to have graduated from an American or Canadian dental school accredited by the ADA Council on Dental Accreditation. A few states, however, have programs that draw foreign dental graduates into underserved areas and allow them to practice for 2 years, after which they can pursue a regular license. In Maryland, for instance, the board of dentistry issues licenses to pediatric dentists that are limited to graduates of a United States–based residency program who practice in a sponsoring hospital, clinic, or dental school.

A few states have changed their legal and regulatory framework to foster innovation, improve consistency, and make scientifically sound recommendations to legislatures. California has established a legal authority for its health department to operate workforce pilot projects. Under this program, schools, clinics, hospitals, or government entities can apply to develop a new type of provider or to propose a new scope of practice or supervision level for existing providers. This program was used to develop and test Registered Dental Hygienists in Alternative Practice, and the authority was made permanent by the legislature in 1997. It currently is being used to develop a Community Oral Health Professional, an innovative dental auxiliary designed to assist patients who have special needs; hygienists with a slightly expanded scope of practice will work in collaborative practice with a dentist, using teledentistry communication technology to provide consultations.

Further, to reduce the difficulty with interstate movement and consumer and regulatory confusion, the Pew Commission favored uniform standards to measure providers’ knowledge and skills and recommended that states use consistent regulatory terminology coupled with reciprocal licensure by endorsement. The Physician Payment Review Commission endorsed model practice acts for practitioners. Three national associations have called for standardized terminology. Montana adopted a Uniform Licensing Act in 1995.

Another key element of dental practice acts is a little-known set of provisions that govern who can own a dental practice or employ a dentist. Few state legislators are familiar with these laws, which are called “bans on the corporate practice of dentistry.” Their modification is a seldom-exercised policy lever that has potential to improve access to care. The ADA believes these laws are necessary to prevent “interference with the professional judgment of a dentist,” but they also have been used to keep out managed care, to stifle alternative delivery system models, to limit the expansion of the safety net, and to preserve dentistry as a cottage industry. They also strictly limit dentists’ choices in how and where they can practice. Fully 26 states define the ownership of a dental practice as an element of practicing dentistry, and five more prohibit anyone but a dentist from operating a dental practice. Exceptions are narrow. For instance, many states have altered the law so that widows of dentists can operate the practice while seeking a buyer. Other exceptions have been made to allow community health centers or charity clinics to hire a dentist, but even these exceptions can be controversial in some states among dentists who believe that clinics are unfair competition. It is important for policymakers to take a fresh look at these laws and to work closely with their state dental society, state health officials, coalitions, safety net hospitals and clinics, and community groups to examine the potential for common-sense safety net exceptions, as well as exceptions for new models of service delivery. For example, access to care could be increased for vulnerable people if a group of nursing homes could employ a dentist to serve its residents or a rural hospital could open a dental clinic and employ a dentist to staff it. Dentists would have more choices for employment if they could belong to a group practice that included pediatricians, nurses, pediatric dentists, hygienists, and orthodontists who wanted to provide “one-stop shopping” for children and their families. Currently, most dental practice laws prohibit all these “corporate” options, although none of them poses a threat to public health or safety.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses