Viral infections

Publisher Summary

There are numerous species of viruses that are capable of infecting humans and the organisms are primarily classified according to the type of nucleic acid present in their genome, that is, DNA or RNA viruses. However, other features such as the arrangement of the protein subunits surrounding the nuclear material, the size of the virion and whether the virion is naked or enveloped are useful in subdividing and speciating the viruses. Certain species of viruses show affinity for specific mammalian cells. This phenomenon, known as tissue tropism, is exemplified by herpes and hepatitis viruses, which replicate in epithelial cells and hepatocytes, respectively. Viruses that show tropism for oral and facial skin epithelium and elicit clinical manifestations in these regions include herpes simplex virus (I and II), varicella zoster virus and the Coxsackie viruses. All of these viruses share a common feature by producing vesiculoulcerative lesions in the oral and perioral regions, accompanied by lymphadenopathy. The papovavirus also infects oral epithelium but it produces papillary rather than vesiculobullous lesions. Cytomegalovirus and mumps virus demonstrate tropism for salivary gland tissue with sialadenopathy as the major clinical finding.

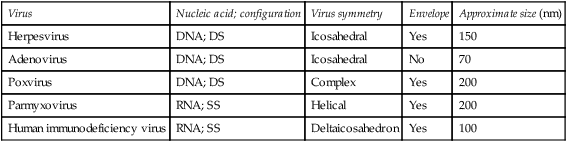

There are numerous species of viruses capable of infecting humans and the organisms are primarily classified according to the type of nucleic acid present in their genome, i.e. DNA or RNA viruses. However, other features such as the arrangement of the protein subunits (capsids) surrounding the nuclear material, the size of the virion and whether the virion is naked or enveloped are useful in subdividing and speciating the viruses (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1

Examples of virus classification according to structure and composition

| Virus | Nucleic acid; configuration | Virus symmetry | Envelope | Approximate size (nm) |

| Herpesvirus | DNA; DS | Icosahedral | Yes | 150 |

| Adenovirus | DNA; DS | Icosahedral | No | 70 |

| Poxvirus | DNA; DS | Complex | Yes | 200 |

| Parmyxovirus | RNA; SS | Helical | Yes | 200 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | RNA; SS | Deltaicosahedron | Yes | 100 |

Certain species of viruses show affinity for specific mammalian cells. This phenomenon, known as tissue tropism, is exemplified by herpes and hepatitis viruses which replicate essentially in epithelial cells and hepatocytes respectively. Viruses that show tropism for oral and facial skin epithelium and elicit clinical manifestations in these regions include herpes simplex virus (I and II), varicella zoster virus and the Coxsackie viruses. All of these viruses share a common feature by producing vesiculoulcerative lesions in the oral and perioral regions, usually accompanied by lymphadenopathy (Table 10.2). The papovavirus (e.g. papillomavirus) also infects oral epithelium but it produces papillary rather than vesiculobullous lesions. Cytomegalovirus and mumps virus demonstrate tropism for salivary gland tissue with sialadenopathy as the major clinical finding.

Table 10.2

Classification of black pigmented Bacteroides species found in the human mouth

| Virus/Disease | Distribution site |

| Herpes simplex I | |

| Primary herpes | |

| Gingivostomatitis | Marginal gingivae and mucosae with vesicles and ulcers |

| Skin | Localized dermal eruptions |

| Ocular | Palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva |

| Eczema hepeticum (Kaposi’s varicelliform eruptions) | Generalized oral and dermal eruptions with pustule formation |

| Secondary herpes | |

| Labialis | Vesicles on vermillion border |

| Intraoral | Clusters of small vesicles and ulcers on palatal gingiva or mandibular gingiva |

| Varicella zoster | |

| Primary (chickenpox) | Trunk and face with a few isolated oral vesicles |

| Secondary (shingles) | Unilateral vesicles stopping at midline and following the distribution of branches of Vth cranial nerve |

| Coxsackie virus, group A | |

| Herpangina | Soft palate and faucial pillars |

| Hand, foot and mouth disease | Movable mucosa, arms below elbows, legs below knees |

| Paramyxoviruses | |

| Measles | Punctate microulcers near parotid duct orifice (Koplik’s spots) 2–3 days prior to rash |

| Mumps | Unilateral or bilateral parotid swelling |

Herpes virus infections

Primary herpes simplex infection

The clinical features of primary herpetic stomatitis consist of an initial stage where there is a mild to severe fever, enlarged lymph nodes and pain in the mouth and throat. Subsequently, variable numbers of vesicles develop haphazardly on the surface of the oral mucosa, although the tongue, buccal mucosa and gingiva are most commonly affected in primary gingivostomatitis. The vesicles quickly rupture to form small round or irregular superficial ulcers with erythematous haloes and greyish-yellow bases (Figure 10.1

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses