The comprehensive treatment of cleft lip and palate deformities requires thoughtful consideration of the anatomic complexities of the deformity, and the delicate balance between intervention and growth. The surgical reconstruction of clefts requires that the surgeon maintain a cognitive understanding of the complex malformation itself, the varied operative techniques employed, facial growth considerations, and the psychosocial health of the patient and family. This article describes the overall reconstructive approach for repair of the unilateral cleft lip and nose deformity using the rotation-advancement repair technique modified from the original description by Millard, still the most common version of unilateral cleft lip and nose repair in the world. Several other techniques exist and are used in various forms by most surgeons. To date, no technique has definitively been proven to produce the best results.

The comprehensive treatment of cleft lip and palate deformities requires thoughtful consideration of the anatomic complexities of the deformity and the delicate balance between intervention and growth. The primary cleft lip and nose repair occurs first, and sets the stage for the remainder of the procedures. Specific goals of surgical care for children born with cleft lip and palate include:

- •

Normalized aesthetic appearance of the lip and nose

- •

Intact primary and secondary palate

- •

Normal speech, language, and hearing

- •

Nasal airway patency

- •

Class I occlusion with normal masticatory function

- •

Good dental and periodontal health

- •

Normal psychosocial development

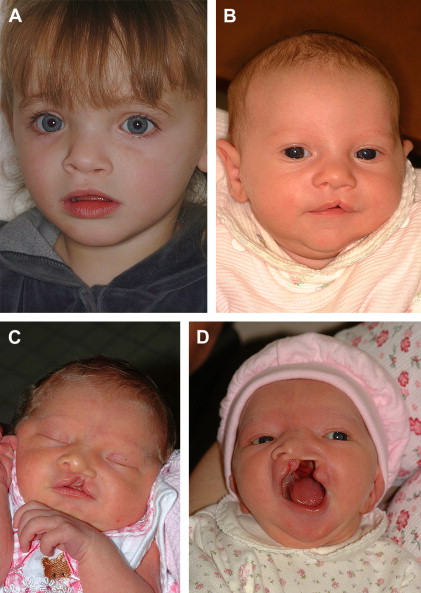

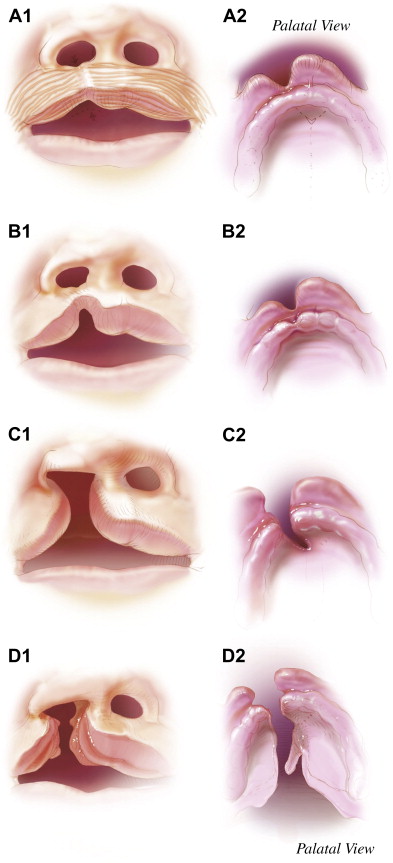

The surgical reconstruction of clefts requires that the surgeon maintain a cognitive understanding of the complex malformation itself, the varied operative techniques employed, facial growth considerations, and the psychosocial health of the patient and family. This article aims to present the overall reconstructive approach for repair of the unilateral cleft lip and nose deformity using the rotation-advancement repair technique modified from the original description by Millard. Several other techniques exist and are used in various forms by most surgeons. In fact, many surgeons use a combination of techniques described in this publication to tailor their approach for each cleft. The heterogeneity of clefting requires a customized approach, and the surgeon can benefit from understanding several different operative approaches ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). The technique described here and used by the authors is primarily based on what is still the most common version of unilateral cleft lip and nose repair in the world. The reader is encouraged to fully evaluate this version as well as the multitude of descriptions available for the other techniques described in this issue. To date, no technique has definitively been proven to produce the best results. Thus, as with many surgical techniques, the surgeon is left to make the best decisions possible based on personal experience, mentoring, the available literature, and continual evaluation of personal outcomes.

Treatment planning and timing

The timing of cleft lip and palate repair is controversial. Despite several meaningful advancements in the care of patients with cleft lip and palate, a lack of consensus exists regarding the timing and specific techniques used during each stage of cleft reconstruction. Surgeons must continue to carefully balance the functional needs, aesthetic concerns, and the issue of ongoing growth when deciding how and when to intervene. In no other type of surgical problem is the issue of early surgery’s effect on growth more apparent than in the treatment of cleft lip and palate deformities. The decision to surgically manipulate the tissues of the growing child should not be made lightly, and should take into account the possible growth restriction that can occur with early surgery. Nevertheless, many patients with congenital deformities will benefit from surgical intervention based on functional or psychosocial reasons. Understanding the growth and development of the craniofacial skeleton is critical to the treatment planning process. In many cases, waiting for a greater degree of growth to occur is advantageous unless compelling functional or aesthetic issues are present that cannot or should not wait.

Due to many different treatment philosophies, the timing of treatment interventions is considerably variable amongst cleft centers. Therefore, it is difficult to produce a timing regimen that everyone agrees upon. Each stage of surgical reconstruction and the suggested timing based on the patient’s age are presented in Table 1 . Special considerations may alter the sequencing or timing of the various procedures based on individual functional or aesthetic needs. It should be noted that significant differences exist worldwide regarding the timing of different repairs. This timing varies greatly and, as of yet, cannot be guided by truly definitive outcome research.

| Cleft lip repair | After 10 weeks |

| Cleft palate repair | 9–18 months |

| Pharyngeal flap or pharyngoplasty | 3–5 years or later based on speech development |

| Maxillary/alveolar reconstruction with bone grafting | 6–9 years based on dental development |

| Cleft orthognathic surgery | 14–16 years in girls, 16–18 years in boys |

| Cleft rhinoplasty | After age 5 years, but preferably at skeletal maturity; after orthognathic surgery when possible |

| Cleft lip revision | Anytime once initial remodeling and scar maturation is complete, but best performed after age 5 years |

Cleft lip repair is generally undertaken at some point after 10 weeks of age. One advantage of waiting until the child is 10 to 12 weeks old is that it allows a complete medical evaluation of the patient so that any associated congenital defects affecting other organ systems (eg, cardiac or renal anomalies) may be uncovered. The surgical procedure itself may be easier when the child is slightly larger, and the anatomic landmarks more prominent and well defined. The anesthetic risk-related data historically suggested that the safest time period for surgery in this population of infants could be outlined simply by using the “rule of 10s.” This rule referred to the idea of delaying lip repair until the child was at least 10 weeks old, 10 pounds in weight, and with a minimum hemoglobin value of 10 dL/mg. Today more sophisticated pediatric anesthetic techniques, advances in intraoperative monitoring, and improved anesthetic agents have all resulted in the ability to provide safe general anesthesia much earlier in life. Despite the ability to provide safe anesthesia earlier, there is no measurable benefit to performing lip repair before 3 months of age. Some surgeons have advocated that lip repair be performed in the first days of infancy, based on the idea of capitalizing on early “fetal-like” healing. Unfortunately, these hoped-for benefits have not been observed, and problems with excessive scarring and less favorable outcomes have been encountered instead. Children may have more scarring at this early age, and their tissues are smaller and more difficult to manipulate. The esthetic outcomes consequently may be worse if surgery is performed at an earlier age, and because there are no clear benefits to earlier repair, the recommendations for repair remain at approximately 3 months old.

As with the timing of other interventions, lip and nasal revision is best reserved for when most growth is complete. Most of the lip and nasal growth is complete after age 5 years. Lip revision may be considered just before school age at about 5 years old or later. However, this may be performed earlier if the deformity is severe. Nasal revision is performed after age 5 years, as most of the nasal growth is also complete by this time. If orthognathic reconstruction is likely, then rhinoplasty is usually best performed after orthognathic surgery, as maxillary advancement improves many characteristics of nasal support. However, when nasal deformity is particularly severe, rhinoplasty can be considered earlier even if orthognathic surgery is expected. Multiple early revisions of the lip or nose should be avoided so that excess scarring does not potentially impair ongoing growth.

Cleft lip and nose repair

Presurgical Taping and Presurgical Orthopedics

Facial taping with elastic devices may be used for application of selective external pressure, and may allow for improvement of lip and nasal position before the lip repair procedure. In the authors’ opinion these techniques often have greater impact in cases of wide bilateral cleft lip and palate, in which manipulation of the premaxillary segment may make primary repair technically easier. Although one of the basic surgical tenets of wound repair is to close wounds under minimal tension, attempts at improving the arrangement of the segments using taping methods have not shown a measurable improvement.

Some surgeons prefer presurgical orthopedic (PSO) appliances rather than lip taping to achieve similar goals. PSO appliances are composed of a custom-made acrylic baseplate that provides improved anchorage in the molding of lip, nasal, and alveolar structures during the presurgical phase of treatment. Although the use of appliances probably makes for an easier surgical repair, there has been a lack of clinical evidence to demonstrate that there is any measurable improvement in aesthetics of the nose or lip, dental arch relationship, tooth survival, or occlusion of the patient. Studies have looked at the dental arch relationships and other outcomes in patients who have infant PSO devices, and no improvement has been seen. In addition, no long-term improvement in speech outcome has been demonstrated in patients who had PSOs. Furthermore, concerns regarding potential negative consequences of these types of appliances have been raised. PSOs also add significant cost and time to treatment early in the child’s life. Some appliances require a general anesthetic for the initial impression used to fabricate the device. Frequent appointments are necessary for monitoring of the anatomic changes and periodic appliance adjustment.

The Latham appliance was popular for expanding and aligning the maxillary segments of the patient with a cleft palate. The appliance is a pin-retained device that is inserted into the palate with acrylic extensions onto the alveolar ridges. A screw mechanism is then used to manipulate the segments as desired. The Latham appliance in conjunction with gingivoperiosteoplasty has been shown to be associated with significant growth restriction of the midface when used in infancy to approximate the segments for repair. Children who have had Latham appliances have been shown to have significant midfacial growth restriction in adolescence 100% of the time, whereas children who had not had the Latham appliance have midface hypoplasia much less frequently.

The Grayson nasoalveolar molding appliance has become popular with some centers in attempts to manipulate the segments without pin retention before lip and nose repair. The nasoalveolar molding (NAM) appliance is adjustable by removing or adding acrylic and manipulating protrusive elements that attempt to mold the nasal cartilages. This device attempts to align and optimize the position of the alveolar segments, lip structures, and nasal cartilage to improve repair. Unfortunately, the hoped-for advantages of this appliance have not been realized. In addition, no long-term data are available regarding growth in the craniofacial skeleton after using this protocol. The limited short-term data that are available cannot be extrapolated to determine the ultimate outcome on growth, function, or aesthetics. Many surgeons use gingivoperiosteoplasty in conjunction with the PSO, using limited flaps to close the alveolus cleft during the primary repair of the lip or palate. Many surgeons who use this appliance in conjunction with their primary lip repairs perform a gingivoperiosteoplasty in an attempt to have bone form at the alveolus. This procedure is more easily performed with the segments aligned in close proximity, as the flaps are small. Experiences with similar techniques in the 1960s involving primary bone grafting were poor with respect to growth. Subsequent studies have confirmed the high incidence of growth restriction in this population. In addition, there have been no convincing long-term objective data showing improvement in either lip or nose aesthetics.

In their current state of technical refinement, there is no compelling evidence that any of the PSOs offer an improved outcome with respect to aesthetics, function, or growth in patients with cleft lip and palate. Coupled with the fact that appliances are time-consuming, and have a high cost of fabrication and use, it is difficult to advocate their uniform use. As with other interventions considered for patients with clefts, costly and unproven interventions should be avoided, although they may prove to be helpful in select cases. There may be a subset of more severe clefts that do benefit from the devices. It is hoped that long-term data will be forthcoming to help determine which specific patients may benefit from PSO appliance treatment.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses