This article reviews the evidence for saliva diagnostics and some antibacterial concepts with potential to interfere with the caries process. It concludes that there is incomplete evidence to evaluate the role of chair-side tests and to recommend general topical applications of antibacterial agents to prevent caries lesions. However, such measures may be considered to control the disease in caries-active individuals. There is evidence that xylitol has antibacterial properties that alter the oral ecology but the clinical evidence for caries prevention is rated as fair. However, preventive programs should include as many complementary strategies as possible, especially when directed toward caries-active patients. Therefore, any antibacterial intervention should always be combined with a fluoride program, until stronger evidence for its use in caries prevention and management becomes available.

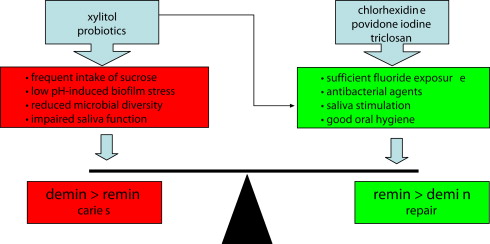

Dental caries forms through a complex interaction over time between acid-producing bacteria and fermentable carbohydrate, and many host factors including teeth and saliva. The process can be described as a dynamic balance between re- and demineralization; if more minerals are lost than gained from the hard tissues over time, a lesion occurs as a sign of the disease. The acids that dissolve the dental hard tissues are produced by bacteria that are general members of the commensal microflora. Therefore, an antibacterial approach to manage caries by controlling or removing bacteria is a key issue in the modern noninvasive medical model of caries treatment. But it is not only the amount of oral bacteria that counts. According to the ecological plaque hypothesis, a caries-inductive environment gives rise to changes in the composition of the biofilm. During periods of constant pH stress, highly acid-producing and acid-tolerating species have an ecological advantage that results in a simplification of the biofilm diversity. Consequently, acid-tolerant microorganisms such as mutans streptococci, lactobacilli, and yeasts are considered as markers of a caries-promoting environment rather than direct and sole causative organisms. The key to modern caries management is to counteract rapid decreases in pH in the dental biofilm and maintain a neutral environment that promotes microbial homeostasis. This article reviews the evidence for some common antibacterial concepts with potential to benefit the biofilm ecology and the caries balance. The value of saliva-based diagnostic tests is addressed. Fluoride plays the most important role in this process and any antibacterial measure should be a complement to regular fluoride exposure.

Primary versus secondary prevention

The prevention of caries builds on the common risk factor approach; by eliminating or reducing factors of importance for the disease, the process can be prevented or controlled. Primary prevention comprises procedures taken before clinical symptoms are detected, whereas secondary prevention, or caries control, aims to hinder progression of existing disease or to reverse its natural course. Consequently, primary prevention is most often community based and relies on general measures, whereas secondary prevention focuses on management of individual patients. The distinction between primary and secondary prevention is important from an evidence-based point of view. Although numerous scientific papers are published every year that evaluate preventive efforts on caries incidence, few are investigations designed to study caries control. In a recent systematic review of the literature by the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care, only 12 caries control studies were included, all of which were of low or moderate quality when assessed according to predetermined criteria. Consequently, it is necessary to generalize findings from primary prevention studies to interventions in terms of caries control. Most caries-preventive trials are performed in children and adolescents or frail elderly patients, and studies dealing with uncompromised adult populations are rare. Again, the findings from children must be extrapolated to adults. Lack of evidence, however, is not the same as lack of effect. Inconclusive or insufficient evidence is most often the result of problems with existing research that is flawed by bias or confounders. Moreover, results based on group levels may not be directly applicable to the individual patient. Best available evidence is only one of the cornerstones in evidence-based medicine; the evidence must always be combined and weighed together with the clinician’s skill and experience as well as the patient’s need, demand, and willingness to pay.

Saliva diagnostics

Saliva samples can provide useful information on the component causes of importance for the caries process:

- •

Host susceptibility: salivary flow rate and buffer capacity as indicators of potential biologic repair

- •

Bacterial challenge: presence and levels of mutans streptococci as indicators of a cariogenic environment

- •

Diet: presence and levels of lactobacilli as indicators of sugar-induced biofilm stress.

Samples can be processed with commercial test kits in the dental office ( Fig. 1 ) and comparative studies indicate that chair-side methods correspond well with conventional laboratory techniques. In addition to the diagnostic values of saliva tests, the outcome can be used as a patient-motivating tool.

Measurement of Saliva Flow Rate

Because saliva malfunction is a major pathologic factor in the caries balance, it is important to evaluate whether the secretion is normal or impaired. Measurement of the secretion rate is necessary to distinguish between subjective xerostomia and objective hyposalivation. Decreased flow rate is a common side effect of radiation therapy and a large number of drugs. In hyposalivation, the saliva is often viscous and foamy and repeated estimations of the flow are advocated to identify alterations over time. Unstimulated saliva is collected by passive drooling whereas stimulated samples are obtained through paraffin chewing. The obtained volume of saliva is divided by the collection time and the secretion rate is expressed as mL/min. Values less than 0.2 and 0.5 mL/min should be considered low for unstimulated and stimulated saliva, respectively.

Buffer Capacity

The buffering capacity is important for maintaining a neutral pH range in the oral biofilm. The chair-side buffer tests reflect the bicarbonate buffer system and identify saliva with poor (yellow), intermediate (green), or normal (blue) buffer capacity. Yellow is significantly associated with a low secretion rate and should be regarded as an indicator of caries risk.

Microbial Enumeration in Saliva

Most chair-side techniques designed for bacterial counts are dip-slides with selective agars for mutans streptococci and lactobacilli, which are inoculated by stimulated saliva. Dip-slides are also available for candida detection. Other kits use bacterial growth and adhesion on specially prepared plastic strips for direct samplings of the tongue (see Fig. 1 ). The samples are incubated for 2 to 4 days at 37°C, or a few days more at room temperature. The density of colony growth is evaluated against a chart and scored in categories from no detectable growth to high counts (≥10 6 colony-forming units [cfu]). The long time span from sampling to final result is a drawback for saliva diagnostics and recently, rapid semiquantitative tests to detect high counts of mutans streptococci have been launched. The salivary bacterial counts are generally considered to adequately reflect the levels in the biofilm but it is important to check whether the patient is, or has recently been, taking antibiotic medication. Furthermore, sampling immediately after tooth brushing or eating should be avoided.

Saliva diagnostics

Saliva samples can provide useful information on the component causes of importance for the caries process:

- •

Host susceptibility: salivary flow rate and buffer capacity as indicators of potential biologic repair

- •

Bacterial challenge: presence and levels of mutans streptococci as indicators of a cariogenic environment

- •

Diet: presence and levels of lactobacilli as indicators of sugar-induced biofilm stress.

Samples can be processed with commercial test kits in the dental office ( Fig. 1 ) and comparative studies indicate that chair-side methods correspond well with conventional laboratory techniques. In addition to the diagnostic values of saliva tests, the outcome can be used as a patient-motivating tool.

Measurement of Saliva Flow Rate

Because saliva malfunction is a major pathologic factor in the caries balance, it is important to evaluate whether the secretion is normal or impaired. Measurement of the secretion rate is necessary to distinguish between subjective xerostomia and objective hyposalivation. Decreased flow rate is a common side effect of radiation therapy and a large number of drugs. In hyposalivation, the saliva is often viscous and foamy and repeated estimations of the flow are advocated to identify alterations over time. Unstimulated saliva is collected by passive drooling whereas stimulated samples are obtained through paraffin chewing. The obtained volume of saliva is divided by the collection time and the secretion rate is expressed as mL/min. Values less than 0.2 and 0.5 mL/min should be considered low for unstimulated and stimulated saliva, respectively.

Buffer Capacity

The buffering capacity is important for maintaining a neutral pH range in the oral biofilm. The chair-side buffer tests reflect the bicarbonate buffer system and identify saliva with poor (yellow), intermediate (green), or normal (blue) buffer capacity. Yellow is significantly associated with a low secretion rate and should be regarded as an indicator of caries risk.

Microbial Enumeration in Saliva

Most chair-side techniques designed for bacterial counts are dip-slides with selective agars for mutans streptococci and lactobacilli, which are inoculated by stimulated saliva. Dip-slides are also available for candida detection. Other kits use bacterial growth and adhesion on specially prepared plastic strips for direct samplings of the tongue (see Fig. 1 ). The samples are incubated for 2 to 4 days at 37°C, or a few days more at room temperature. The density of colony growth is evaluated against a chart and scored in categories from no detectable growth to high counts (≥10 6 colony-forming units [cfu]). The long time span from sampling to final result is a drawback for saliva diagnostics and recently, rapid semiquantitative tests to detect high counts of mutans streptococci have been launched. The salivary bacterial counts are generally considered to adequately reflect the levels in the biofilm but it is important to check whether the patient is, or has recently been, taking antibiotic medication. Furthermore, sampling immediately after tooth brushing or eating should be avoided.

Evidence for salivary diagnostics in caries activity assessment

Although it is obvious that saliva plays a significant role in the caries process, the benefits of salivary diagnostics for the individual patient are not clear-cut. Threshold limits may vary among different individuals and the so-called normal values for flow rate are more reliable in populations than among individuals for screening purposes. In spite of extensive research on the topic in recent decades, systematic reviews are still rare. There is good evidence to suggest that presence of mutans streptococci in saliva of young caries-free children is associated with a considerable increased caries risk. The findings concerning lactobacilli, however, are contradictory and less conclusive. Among the nonmicrobial variables, salivary flow rate is the most important single parameter, whereas the buffer effect shows only a weak negative association with caries activity. Furthermore, a significant association between one or more saliva factors and caries established in cross-sectional studies does not mean that those factors are useful as predictors. The diagnostic or predictive value of saliva tests must be evaluated in prospective longitudinal studies, and further research is required to eradicate the questions concerning its clinical routine use.

Antimicrobial and antiseptic approaches

Although tooth cleaning is probably the most common way of eliminating bacteria, the focus in this article is on topical applications of chemotherapeutic agents and measures that may interfere with the caries balance. When evaluating the evidence for treatment effects, it is important to distinguish between results obtained with microbial or clinical end points. The former are called intermediate or surrogate end points because they may be indicative from an evidence-based point of view. For example, numerous good-quality trials convincingly show significant mutans streptococci suppression after chlorhexidine (CHX) therapy, but the studies reporting the effect on lesion incidence and control are fewer and inconsistent. Only studies with caries lesions as an end point should therefore be used for treatment recommendations and evidence-based guidelines.

Topical application of antibacterial agents

The most commonly suggested antiseptic agents to prevent and manage dental caries are CHX, povidine iodine, triclosan, and silver diamine fluoride (SDF). They all act on the protective side of the caries balance ( Fig. 2 ).

CHX

CHX gluconate is effective against a wide variety of gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, aerobes, facultative anaerobes, and yeast. The use in general medicine is primarily for surgical scrub, hand rinse, and cleansing skin wounds. Within dentistry, CHX is the gold standard for plaque and gingivitis control and for irrigation during periodontal procedures. Another common indication is temporary support of oral hygiene in medically compromised and disabled patients, including sick children. For oral use, CHX is available as rinsing solutions, gels, or dental varnishes at various concentrations (0.1%–40%; only 0.12% and 1% concentrations are available in the United States). The drug has a strong affinity to oral structures and the mechanism of action is 2-fold; at lower concentrations, CHX interferes with cell wall transportation and metabolic pathways, whereas higher concentrations cause precipitation of the intracellular cytoplasm. The bacterial population in plaque and saliva can be reduced by 80% immediately after a 0.2% CHX rinse. Long-term use of CHX mouth rinse does not seem to confer any significant changes in bacterial resistance or overgrowth of potentially opportunistic organisms. The number of target bacteria in plaque, such as mutans streptococci, always returns to baseline within weeks or months after discontinuation of therapy. Extensive use of CHX for long periods can cause stained teeth, especially on resin restorations, and alter taste sensation.

The traditional indication for CHX treatment is caries control in caries-active individuals, and the best mode of professional treatment seems to be intensive treatments with gel in custom-made soft trays, 3 × 5 minutes for 2 consecutive days. For home-care use, a 5-minute application once a day for 14 days may be preferred. Varnishes exert a slow release of CHX but must be reapplied at regular intervals. Detergents in toothpaste can inactivate CHX, and tooth brushing should therefore be separated from the agent by at least 2 hours. Although commonly used in Europe and Asia, no CHX formulation is approved for caries prevention in the United States.

CHX and Caries Prevention/Control

The first major prospective trial with CHX gel indicated an 85% reduction of caries in teenagers, with initially high counts (>10 6 cfu/mL) of salivary mutans streptococci. Another successful approach for proximal caries control was to combine repeated CHX gel applications with professional interdental flossing. A meta-analysis of all the early investigations revealed a prevented fraction of 46%, but this figure was probably affected by publication bias because positive and novel findings are more likely to be published than negative. The initially successful findings with CHX regimes have not been confirmed in more recent trials conducted in situ or in high-risk children. Consequently, later systematic reviews have resulted in more cautious conclusions, indicating a modest caries-preventive effect of around 10% to 26% ( Table 1 ). Concerning CHX varnish, a recent review by Zhang and colleagues concluded a moderate caries-inhibiting effect when varnish is applied every 3 to 4 months but the beneficial effect was questionable in low-caries populations. The findings in children are parallel with those in older adults; a recent study failed to show that regular rinsing with CHX could reduce root caries and preserve sound tooth structure in elderly people.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses