As the most anterior point of the face, the nose frequently lends itself to traumatic injury. Secondary to a rich vascular supply, the nasal complex is a common source of hemorrhage (epistaxis) in the trauma victim. Treatment of epistaxis is dictated by the etiology and the source of bleeding; thus knowledge of facial anatomy and a thorough physical evaluation of the patient will readily guide the proper treatment.

The incidence of severe hemorrhage resulting from maxillofacial trauma is rare, but is potentially life threatening. When maxillofacial injuries lead to life-threatening hemorrhage, the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation should be managed initially within the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol.

Treatment of life-threatening nasal hemorrhage associated with post-traumatic craniofacial fracture is principally based on aggressive resuscitation combined with anterior and posterior nasal packing, which should be performed upon presentation in the emergency room or as soon as possible. Ardekian reported various treatment modalities for traumatic bleeding from the maxillofacial region, including nasal packing, reduction of fractures, arterial ligation, angiography, and selective embolization.

Because post-traumatic nasal bleeding frequently originates from lacerated arteries deep in the fractured facial skeleton and proximal to the nasal cavity, it is not always possible to attenuate bleeding by nasal packing alone. If nasal hemorrhage persists and blood pressure remains unstable after nasal packing, direct surgical ligation of the bleeding vessels or fixation of facial fractures is conventionally recommended. However, in the setting of multisystem trauma and shock, surgery to ligate the deep hemorrhaging nasal vessels may be too time-consuming and risky. In these cases, transarterial embolization (TAE) can offer an alternative to control hemorrhage. Early diagnosis and intervention of life-threatening hemorrhage is essential for a favorable outcome.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

Epistaxis is the result of direct or indirect vascular injury within the nasal complex and its associated sinuses. Epistaxis may present as a result of tumors, orthognathic/cosmetic surgery, intubation, medications, arteriovenous malformations, and coagulopathies. However, in the setting of facial trauma, the more common etiologies are assault, motor vehicle collision (MVC), gunshot wounds, and athletic injuries. Identification of the etiology of epistaxis is crucial in managing the patient and providing appropriate treatment. With this in mind, epistaxis as a result of direct vascular injury may only need local measures to control the event, whereas, in the presence of a coagulopathy treatment, it will likely need systemic management in addition to local management.

Dyscrasias

Coagulopathies alone can cause significant epistaxis and must always be considered in the trauma victim when hemorrhage is disproportionate to the mechanism of injury. Anticoagulant medication or history of bleeding dyscrasias should always be determined and coagulation assays obtained when indicated. Reversal with appropriate medications, blood products, or coagulation factors may be necessary, in concert with local measures. All individuals with excessive epistaxis should be evaluated for dyscrasias and receive necessary fluid resuscitation and reversal early to prevent hemodynamic instability.

Dyscrasias

Coagulopathies alone can cause significant epistaxis and must always be considered in the trauma victim when hemorrhage is disproportionate to the mechanism of injury. Anticoagulant medication or history of bleeding dyscrasias should always be determined and coagulation assays obtained when indicated. Reversal with appropriate medications, blood products, or coagulation factors may be necessary, in concert with local measures. All individuals with excessive epistaxis should be evaluated for dyscrasias and receive necessary fluid resuscitation and reversal early to prevent hemodynamic instability.

Pseudoaneurysm Of The Internal Carotid Artery

An initially silent, but very serious consequence of maxillofacial injury is traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the internal carotid (TPICA). Initiated by blunt as well as penetrating trauma, pseudoaneurysms form when an artery has a partial transection. Resulting leakage of blood from the vessel forms a hematoma within the surrounding tissue. Tamponade from the hematoma slows bleeding and retains patency of the arterial lumen, preventing clinically significant hemorrhage. Complications from a pseudoaneurysm can manifest anywhere from days to months after the initial trauma, a direct consequence of a re-bleed of the injured vessel. Delayed hemorrhage from the pseudoaneurysm is due to hematoma resolution or tearing of the fibrous capsule wall that can form around the initial hematoma. A TPICA presents as varying degrees of neurologic deficits and hemorrhage, such as recurrent, often substantial epistaxis. TPICA rupture is associated with 30% to 50% mortality and, accordingly, must always be considered in patients with a history of trauma who present with recurrent epistaxis, especially with cranial nerve deficits. Brisk diagnosis and treatment, usually by arterial angiography and embolization, is imperative.

Arterial Anatomy

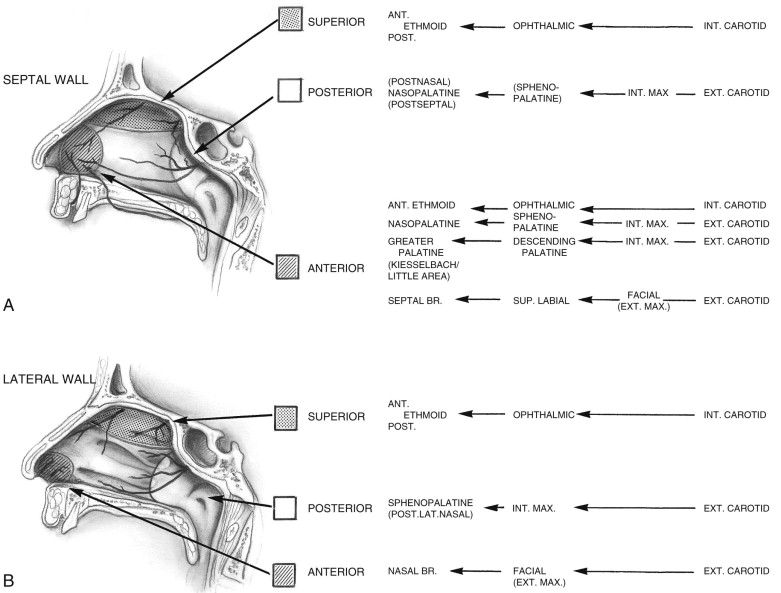

Comprehension of the nasal complex vascularity is essential for proper evaluation and treatment of epistaxis ( Fig. 35-1 ). The arterial supply to the nasal fossa involves branches from both the external and internal carotid arteries. The external carotid artery contributes most of the arterial supply through the internal maxillary (sphenopalatine and greater palatine branches) and facial arteries (superior labial branch). A branch of the internal carotid artery, the ophthalmic artery, supplies the nasal fossa through the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries. The nasal blood supply can be considered to have three main sources with multiple anastomoses: the sphenopalatine (considered the primary source), the superior labial, and the ethmoidal arteries.

Sphenopalatine Artery

The sphenopalatine artery (SPA) serves as the major supply to the nasal fossa and enters the nasal cavity through the sphenopalatine foramen. The foramen is located on the posterior aspect of the lateral nasal wall posterior to the middle turbinate. The SPA most commonly splits into a septal and lateral branch just as it passes through the foramen. Alternatively, the SPA can have three or more branches and may split within the pterygopalatine fossa prior to entering the nasal fossa. These variations are important to consider when attempting surgical ligation.

Superior Labial Artery

The superior labial artery, arising from the facial artery, penetrates the orbicularis oris muscle at the level of the commissure and enters into the nasal osteum superficial to the depressor septi nasi muscle. It supplies the anterior portion of the septum and medial wall of the nasal vestibule through the septal branch.

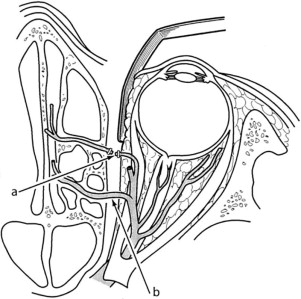

Anterior And Posterior Ethmoidals

The internal carotid arterial supply originates from the ophthalmic artery, entering the orbit along with the optic nerve through the optic canal. After the lacrimal artery divides off the ophthalmic artery, it continues along the superior and medial aspect of the orbit. The anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries split off medially through the orbital wall into the ethmoid sinus, entering the nasal cavity superiorly through the cribriform plate ( Fig. 35-2 ). The anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries usually exit the orbit 24 mm and 36 mm posterior to the lacrimal crest, respectively, leaving the optic nerve only 6 mm behind the posterior ethmoidal arteries. These dimensions are important landmarks in order to avoid optic nerve injury when performing surgical ligation with any variation of the Lynch incision.

Kiesselbach Plexus

The Kiesselbach plexus, also known as the Little area, is a localized region of mucosa of the anteroinferior nasal septum. The plexus is principally supplied by branches and anastomoses of the sphenopalatine, superior labial, and anterior ethmoidal arteries and is the most common site of anterior epistaxis.

Woodruff Plexus

The Woodruff plexus is a network of anastomoses on the lateral nasal wall inferior to the posterior end of the inferior turbinate. Once thought to be the primary source of posterior epistaxis, it is now considered entirely venous and is thought to play a much less important role.

Diagnostic Studies

As for any emergent consult, a brief history of presenting illness, past medical/surgical history, allergies, and current medications should be assessed judiciously. Along with a simultaneous initial survey, the clinician should be able to assess the possible etiology (e.g., traumatic, pharmacologic, postsurgical), severity (amount, duration), and source (anterior or posterior) of the epistaxis.

This initial survey should dictate initial diagnostic studies. In the presence of a severe bleed, and any suspected posterior bleed, the clinician should establish intravenous (IV) access and consider a fluid bolus as well as laboratory tests, including, but not limited to, a complete blood count, coagulation panel, and platelet function assay. Direct inspection should be done only with the proper armamentarium, including a light source, suction, nasal speculum, and bayonet forceps. In cases of mild epistaxis, initial inspection can be performed without packing or a vasoconstrictor. This avoids temporarily hiding the offending vessel. Instead, consider a saline rinse and only use a vasoconstrictor and packing if initial visualization is impractical without attenuating the hemorrhage.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses