The purpose of this case report is to describe the treatment, including 3-year follow-up records, for a patient with hemifacial microsmia. Treatment included the unusual use of temporary anchorage devices to correct the cant of the occlusal plane. The advantages of distraction osteogenesis are discussed. The successful outcome depended on the collaboration of the orthodontist and the craniofacial surgeon.

Hemifacial microsomia is a common birth defect involving first and second branchial arch derivatives. In addition to craniofacial anomalies, there can be cardiac, vertebral, and central nervous system defects. Although most cases are sporadic and a few families consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance have been reported, other families clearly show autosomal dominant inheritance.

Branchial arch dysplasia is characterized by underdevelopment of the ear, mandible, and contiguous bony structures of the cranium and the face. Involvement is usually limited to 1 side of the face. The heterogeneous nature of this malformation results in inconsistent phenotypic expressions and requires a variety of treatment approaches.

Conventionally, for patients with severe deformities, early surgical intervention with autogenous costochondral grafting is indicated. After pubertal growth, mild deformities can be corrected with orthodontic treatment, genioplasty, and unilateral mandibular augmentation, but more severe problems might require bimaxillary surgery.

Distraction osteogenesis has become an accepted treatment method for patients requiring mandibular lengthening because of congenital malformations. In a Web-based survey in Europe, although there was disagreement on the essential steps in the distraction procedures, more than 80% of the respondents considered patients with hemifacial microsomia, cleft lip and palate, and Crouzon syndrome suitable for distraction osteogenesis.

Distraction osteogenesis was used as early as 1905 by Codivilla and later popularized by Ilizarov. Synder et al in 1973 and Michieli and Miotti in 1977 reported mandibular lengthening by gradual distraction in animal models. In 1992, mandibular lengthening by distraction osteogenesis was used in a human mandible by McCarthy et al in a patient with hemifacial microsomia; since then, it has been applied to the various bones of the craniofacial skeleton. Molina and Ortiz Monasterio reported mandibular elongation by distraction as a farewell to major osteotomies.

Meanwhile, temporary skeletal anchorage devices have also revolutionized the world of orthodontics since their introduction in the anchorage armamentarium. Miniscrews allow the management of wider discrepancies than those treatable by conventional biomechanics because force can be applied directly from the bone-borne anchor unit. Therefore, miniscrews not only free orthodontists from anchorage-demanding cases, but they also enable clinicians to have good control over tooth movement in 3 dimensions.

This article presents the records of a patient with hemifacial microsmia treated with distraction osteogenesis and orthodontics. The use of temporary skeletal anchorage devices to save the patient an additional maxillary surgery is emphasized.

Diagnosis and etiology

The patient was a 17-year-old Lebanese girl whose primary complaint was her asymmetrical appearance ( Fig 1 ). She had hemifacial microsomia as part of a wider multiple Tessier cleft with a notch in her left nostril and upper eyelid coloboma. These could correspond to a mild Tessier cleft. Her hemifacial microsomia was a Tessier cleft in his classification. Her face was asymmetrical, with an underdeveloped left side, a chin deviation toward the affected side, and a retrusive chin in the profile view, along with lip incompetence. There was no history of craniofacial deformities in her family.

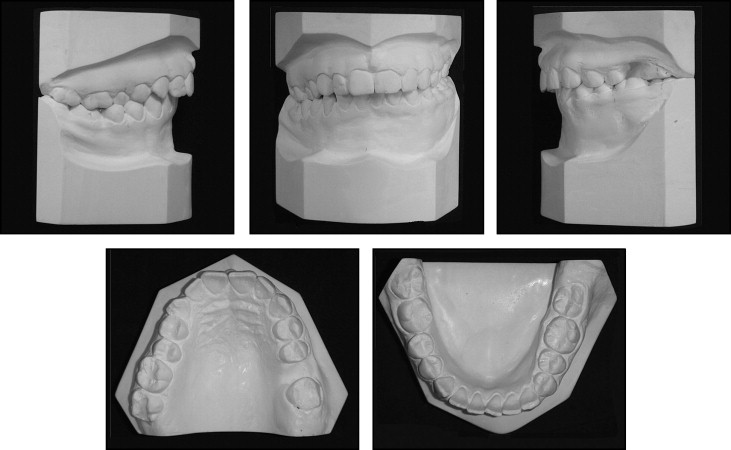

The intraoral examination showed frontal canting of the occlusal plane, mandibular midline deviation of 2 mm to the right and a crossbite of the maxillary right second premolar. There was extreme crown wear on the mandibular right canine. The maxillary left first molar was missing, and there were minor rotations in the maxillary and mandibular teeth. Moreover, she had an asymmetric sagittal occlusal relationship: complete Class II malocclusion on the right and Class I on the left ( Figs 1 and 2 ).

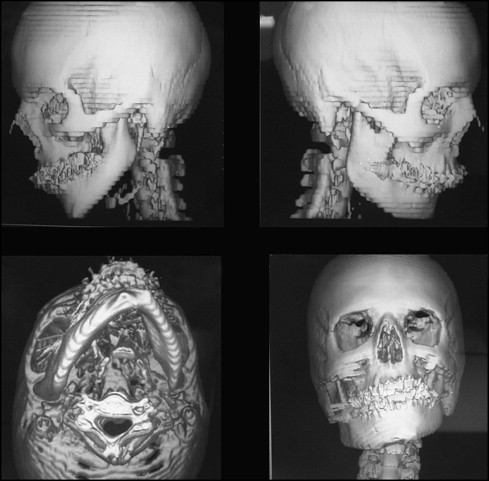

The computed tomography scan confirmed the skeletal components of this malformation and showed the anatomically different growth patterns between the left and right rami, along with deviation of menton ( Fig 3 ).

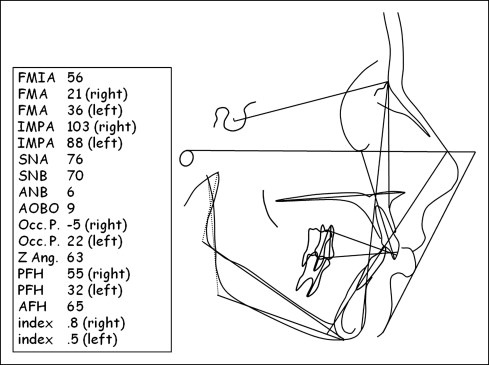

The cephalometric analysis pointed to a skeletal Class II relationship, with a hypodivergent pattern on the normal side and a hyperdivergent pattern on the affected side. The Z-angle indicated a convex profile with a retrusive chin and a protrusive lower lip.

The posteroanterior cephalometric radiograph showed a deviated menton toward the affected side (midsagittal plane-Me, 16 mm to the left; midsagittal plane/Me, 8°) and canting of the occlusal plane (orbital plane/mandibular occlusal plane, 11°) ( Figs 4 and 5 ).

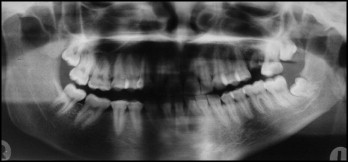

The panoramic radiograph illustrated the difference in ramus sizes between the left and right sides, as well as a retained root fragment from the maxillary left first molar, and absence of the mandibular right third molar ( Fig 6 ).

Treatment objectives

- 1.

Correct the facial asymmetry by lengthening the shorter ramus and moving the chin to the right side.

- 2.

Correct the skeletal Class II relationship and improve the profile.

- 3.

Correct the canting of the occlusal plane and obtain a dental Class I relationship of the canines and molars.

- 4.

Close the space of the maxillary left first molar.

Treatment objectives

- 1.

Correct the facial asymmetry by lengthening the shorter ramus and moving the chin to the right side.

- 2.

Correct the skeletal Class II relationship and improve the profile.

- 3.

Correct the canting of the occlusal plane and obtain a dental Class I relationship of the canines and molars.

- 4.

Close the space of the maxillary left first molar.

Treatment alternatives

Based on the objectives, 3 treatment options were proposed.

- 1.

Combined orthodontic and surgical treatment with maxillary clockwise frontal rotation and mandibular advancement along with costochondral grafting to elongate the shorter ramus.

- 2.

Combined orthodontic and surgical treatment with maxillary clockwise frontal rotation and distraction osteogenesis to advance the mandible and elongate the shorter ramus.

- 3.

Combined orthodontic and distraction osteogenesis treatment without orthognathic surgery. The canting of the maxillary occlusal plane after distraction osteogenesis would be corrected with individual tooth eruptions and temporary skeletal anchorage devices.

In all conditions, the patient was aware that some minor refinements after her treatment could be needed for better results (ie, genioplasty and restorative buildup).

To decrease the number of surgeries and the requirement for a large amount of mandibular and maxillary bone grafting, the third option was chosen.

Treatment progress

The active treatment was divided into 3 phases: predistraction, distraction and consolidation, and postdistraction.

In the predistraction phase ( Fig 7 ), standard edgewise single brackets (0.022 in) were placed on the maxillary teeth first; bracketing of the mandibular teeth was delayed for 4 months to start the leveling with Class III elastics to maintain the mandibular incisor position after leveling. The maxillary molars were bonded with buccal tubes, and the mandibular second molars were banded. The space of the maxillary left first molar was closed, and the mandibular and maxillary arches were aligned and leveled with a 0.020 × 0.025-in stainless steel ideal wire.